Charles Francis Adams Sr was the youngest of 3 sons of John Quincy Adams and the grandson of John Adams, which is about as illustrious a family tree as one could imagine. As you’d expect of a northern elite family, he attended Boston Latin and Harvard, then studied law with Daniel Webster. He opened a law practice, was elected 3 times to the Massachusetts House and once to the Massachusetts Senate.

But politics was not really his game, and he knew it. Instead, he purchased and edited the Boston Whig, a newspaper for the common people, who were more liberal minded than those he grew up with and wanted to see change faster. His initial successes came as an editor. This paper went from obscurity to national acclaim under his editorship, so much so that he was offered a national candidacy at the age of 41. He edited his grandmother’s, Abigail Adams, letters; then finished his father’s incomplete biography of his grandfather, including a highly acclaimed collection of his letters, which ultimately became the first Presidential Library.

Many of his relatives found the burden of carrying on the family tradition of public service impossible to live up to. Many retired to private life, while others broke under the strain. Charles Francis Adams was the youngest of 3 brothers; his older brothers were George Washington Adams (1801–1829) and John Adams II (1803–1834). All 3 were rivals for the same woman, their cousin Mary Catherine Hellen, who lived with the Adams family after the death of her parents. In 1828, John married Mary in a White House ceremony, and both Charles and George declined to attend. John was the father of an out-of-wedlock child born later that year to a woman who was the chambermaid to the family’s physician. The child died in infancy. John was a reputed alcoholic who is believed to have committed suicide the next spring.

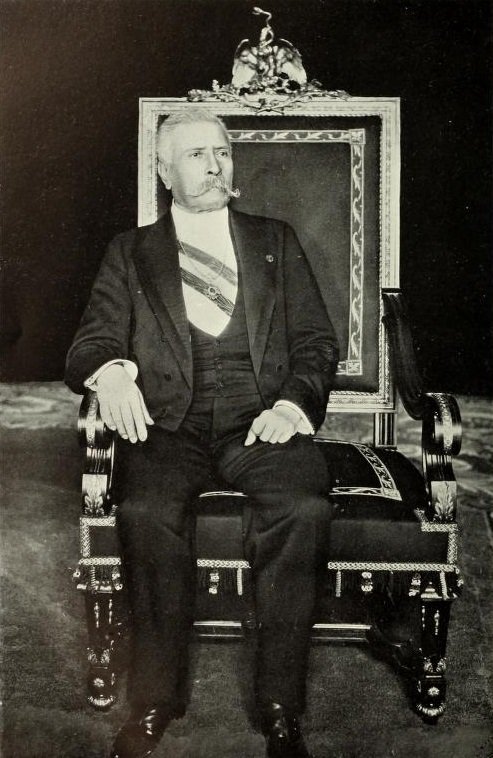

Charles Francis Adams

Instead, Charles Francis married Abigail, the daughter of Peter Chardon Brooks, a Boston millionaire and one of the richest men in Massachusetts. Her father insisted that they wait several years before getting married, as they were too young when they met. Later, Charles Francis Adams said that if not for Abigail Brooks, he would never have accomplished anything in life. After experiencing his brother's death, his marriage to Abigail Brooks, and his reconciliation with his father, Charles Francis became a more focused and goal-oriented person.

Charles opened his own law office but was careless about its operation, and his father criticized Charles for being aimless and irresponsible. Charles and his father had never been close but after Charles' oldest brother died in 1829, John Quincy seemed to show more interest and affection for his two remaining sons. After his father’s presidency, he spent eighteen years representing the Quincy district; Charles Francis assumed the care of the property the elder Adams possessed.

The controversy over slavery, however, propelled Charles Francis into prominence. In the Massachusetts legislature, where he served from 1840 to 1845, Adams became a leader of conservative antislavery members who concentrated on resisting the encroachments of "slave power." With the issue of the annexation of Texas, Adams became one of the leaders of the "conscience Whigs," that wing of the Whig Party that demanded guarantees that slavery would not be expanded westward. The Conscience Whigs in Massachusetts merged with the broader "Free Soil" movement in 1848.

Adams unsuccessfully ran for vice president as that party's candidate alongside Martin Van Buren. Adams disapproved of the Free Soil tendency to ally with other parties in order to achieve election. He became unpopular in the south for his abolitionist views and unpopular in the north for his strict adherence to supporting abolition over elected office.

In 1848, he was the unsuccessful nominee of the Free Soil Party for Vice President of the United States, running on a ticket with former president Martin Van Buren as the presidential nominee. That same year, his father died from a stroke at age 80. He spent most of the 1850s rehabbing the family home in Quincy, today a national park.

In 1859, Adams was elected to the US House of Representatives. He became chair of a northern committee studying how to work for conciliation with the South. Suddenly, the intransigent abolitionist was looking for a solution: the very definition of diplomacy. He supported Seward – not Lincoln – for the presidential nomination. But on his election, Lincoln asked him to serve as US minister to Great Britain, which Adams accepted. This became the work of a lifetime. Give Lincoln props for an amazing recognition of talent.

US Minister to the Court of St James

The US Minister to the Court of St James (Great Britain) was a crucial post. As the U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom from 1861 to 1868, Adams played a crucial role in preventing British recognition of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Through skillful diplomacy and advocacy, he successfully conveyed the Union's perspective and counteracted Confederate efforts to gain international support. Through firm but skillful negotiations, Adams was influential in persuading the British, and by extension the French, not to recognize the Confederacy.

Britain issued a proclamation of neutrality at the beginning of the Civil War on May 13, 1861. The imposition of the blockade forced Britain to take a position on which side it would support. Southern cotton was critical to the textile industry in western England, especially Liverpool. The United States Secretary of State, William Seward, threatened to treat as hostile any country that recognized the Confederacy. Instead, the Confederacy was recognized as a belligerent, but it was premature to recognize it as a sovereign state. Britain remained neutral officially and waited to see how things would develop before making a commitment. Adams did incredible work to keep Britain neutral and prevent the British from going any further in their recognition. Both his father and his grandfather had served in this diplomatic post, and so he was immediately accepted by the British as speaking for the new administration with a wise voice.

Official recognition was tied to the idea of the Union blockade being against a belligerent power rather than an insurrection. Adams managed to navigate this by getting the British to respect the blockade officially while still not recognizing the Confederacy as an independent entity. Because of his own family legacy, he managed to form a friendship with Prince Albert.

One of his main accomplishments was leveraging his friendships to prevent the British from supplying Confederate ironclads. A strong element in Britain wanted to intervene on behalf of the Confederacy. Both the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer had strong sympathies with the South and believed it would win independence. The Prime Minister in particular had a lifelong hostility to the US, and despite opposition to the slave trade and slavery, he believed that dissolution of the Union would benefit the British.

Adams played a key role in preventing the recognition of the Confederacy by the United Kingdom through diplomatic efforts and effective communication. Adams skillfully engaged with British officials, politicians, and influential figures, presenting the Union's case and countering Confederate propaganda. Support of the Confederacy in Britain was popular for several reasons. The primary one was the availability of cheap cotton for English mills.

Adams in London

Britain had lost 2 wars to this fledgling primitive country on the other side of the pond. Further, the idea of a successful democracy remained unappetizing to a government based on a monarchy. Moreover, southern trade especially cotton was very important to British manufacturers. Finally, they knew that if they helped this new country win independence, it would be forever in its debt; which is precisely what empire is about.

He emphasized the Union's commitment to upholding international law, the abolition of slavery, and the economic benefits of maintaining trade relations with the North. Adams emphasized the military and industrial power of the Union, which was vital in dispelling the perception that the Confederacy could achieve a quick and decisive victory. He provided accurate and timely information about Union victories, the strength of the Union army, and the North's ability to sustain the war effort.

Adams warned that meant war with the United States, as well as the cutting off of American food exports, which comprised about a fourth of the British food supply. ”The English people can't eat cotton” was his strong argument, and the Union supplied too much necessary food to England to make war with the United States a realistic action. Losing grain and meat shipments from the United States would mean a huge fall in food supply. It’s fascinating that the Jefferson Davis government believed King Cotton would be decisive, yet it was corn that really was.

Also, the American Navy, increasingly strong, would try to sink British shipping. Britain depended more on American corn than Confederate cotton, and a war with the U.S. would not be in Britain's economic interest.

Adams recognized the significance of public opinion and worked to shape it in favor of the Union. He engaged with the British press, wrote articles and letters to influential publications, and delivered speeches to counter Confederate narratives and generate sympathy for the Union cause.

Adams conveyed to the British government that recognition of the Confederacy would likely strain relations between the United States and the United Kingdom. He made it clear that such recognition would have negative consequences for British trade and international standing, creating a disincentive for British officials to support the Confederacy.

By employing these diplomatic strategies, effectively countering Confederate propaganda, and highlighting the Union's strength, Charles Francis Adams played a crucial role in preventing the recognition of the Confederacy by the United Kingdom. His diplomatic efforts helped to maintain the international isolation of the Confederacy and ultimately contributed to the Union's victory in the Civil War.

Had Britain recognized the Confederacy, and given its aid and assistance, the Civil War would have had an entirely different result. Charles Francis Adams took on this exasperating and vexing assignment. Recognition was a fear of the Union and a pipe dream of the Confederacy. In retrospect, it was never really likely to happen without multiple major successes on the battlefield by the Confederacy. This reality was based on the political situation in Britain more than the circumstances we Americans think the Civil War was about.

Trent Affair

The “Trent Affair” in November 1861 produced public outrage in Britain and a diplomatic crisis. The British predicted a war and Seward threatened to fight. Only Abraham Lincoln kept the crisis in perspective. Ambassador Adams played a crucial role in resolving it, and for a time, things looked bleak. Adams almost single-handedly calmed British anger.

The "Trent Affair” was initiated when an American warship seized two Confederate agents bound for Europe from the British mail ship Trent.A U.S. Navy warship stopped the British steamer Trent and seized two Confederate envoys en route to Europe. On November 8, 1861, the USS San Jacinto, commanded by Union Captain Charles Wilkes, intercepted the British mail packet RMS Trent and removed, as contraband of war, two Confederate envoys: James Murray Mason and John Slidell. The envoys were bound for Britain and France to press the Confederacy's case for diplomatic recognition and to lobby for possible financial and military support.

Public reaction in the United States was to celebrate the capture and rally against Britain, threatening war. In the Confederate states, the hope was that the incident would lead to a permanent rupture in Anglo-American relations and possibly even war, or at least diplomatic recognition by Britain. Confederates realized their independence potentially depended on foreign intervention.

In Britain, there was widespread disapproval of this violation of neutral rights and insult to their national honor. The British government demanded an apology and the release of the prisoners and took steps to strengthen its military forces in British North America and the North Atlantic. PM Palmerston called the action "a declared and gross insult", demanded the release of the two diplomats and ordered 3,000 troops to Canada. In a letter to Queen Victoria on 5 December 1861 he said that if his demands were not met: "Great Britain is in a better state than at any former time to inflict a severe blow upon and to read a lesson to the United States which will not soon be forgotten." In another letter to his foreign secretary, he predicted war between Britain and the Union.

President Abraham Lincoln did not want to risk war with Britain over this issue. “One war at a time” Lincoln told Seward. After some careful diplomatic exchanges, Lincoln admitted that the capture had been conducted contrary to maritime law and that private citizens could not be classified as "enemy despatches”, which was the only possible legal argument. After several tense weeks, the crisis was resolved when the Lincoln administration released the envoys and disavowed Captain Wilkes's actions, although without a formal apology. Slidell and Mason were released, and war was averted. Mason and Slidell resumed their voyage to Europe. Adams basically brokered this resolution, by recognizing the British right to engage in diplomacy as it saw fit while maintaining the Lincoln administration’s position that the war was an internal domestic conflict not an international one.

The resolution of the Trent affair dealt a serious blow to Confederate diplomatic efforts. First, it deflected the recognition momentum developed during the summer and fall of 1861. It created a feeling in Great Britain that the United States was prepared to defend itself when necessary, but recognized its responsibility to comply with international law. Moreover, it produced a feeling in Great Britain and France that peace could be preserved as long as the Europeans maintained strict neutrality in regard to the American belligerents. Lincoln, through Adams, turned a potentially explosive event into a huge net positive. (See more at https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/trent-affair)

Slidell was the designee to represent the Confederacy in France. He failed to bring France into the war, which would not change its position unless Britain made the first move. His major success in the war was negotiating a loan of $15,000,000 from Emile Erlanger & Co. and in securing the ship "Stonewall" for the Confederate government. Slidell, Louisiana is named after him. After the war, he remained in Paris.

Mason was the grandson of George Mason. He was a strong secessionist and white supremacist who strongly favored slavery, wrote the fugitive slave act, and before the war was the chair of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee. You’d think he would have been tough competition for Adams, but in fact his views were so extreme that he was ineffectual as a diplomat and he moved to Paris in 1863 where he hoped he would find a more sympathetic ear. After the war, he lived in exile in Canada, eventually purchasing a huge estate in Alexandria VA with white servants as he believed free blacks to be worthless.

The British Government

In retrospect, Both the Union and the Confederacy overestimated the potential of British recognition. Not only the Queen and Prince, but also the Church, the Commons, and working people adamantly opposed slavery. Still, faced with both a PM and a ruling party that favored the enemy, you can understand the fears.

Lord Palmerston was the Prime Minister and William Gladstone the Chancellor. Their relationship lasted 35 years, both as allies and as political enemies, exchanging jobs several times. Together they dominated British foreign policy, and If they were in agreement, the US was in trouble. With very little cotton reaching Europe except through Union channels, a strong element in Britain, including both Palmerston & Gladstone, wanted to intervene to help the Confederacy.

Palmerston's sympathies in the Civil War were with the Confederate States of America. Although a professed opponent of the slave trade and slavery, he held a lifelong hostility towards the United States, and believed dissolution of the Union would enhance British power. Additionally, the Confederacy "would afford a valuable and extensive market for British manufactures". He expected the Confederacy to achieve its independence.

The British government pulled back from talk of war when the Confederate invasion of the North was defeated at Antietam, and Lincoln announced that he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Palmerston then noted that the only thing positive that had been accomplished by the war was the killing off of thousands of “troublesome Irish and Germans”.

Palmerston and his government were careful to avoid any actions that could be interpreted as favoring either the Union or the Confederacy. While there were debates within his government and among politicians regarding the recognition of the Confederacy, Palmerston ultimately adhered to a policy of non-recognition and neutrality.

Palmerston's government closely monitored the progress of the war, sought to gather accurate intelligence, and maintained diplomatic channels with both sides. However, the British government did not extend official recognition to the Confederacy as an independent nation during Palmerston's tenure.

Overall, Palmerston's approach was one of careful neutrality, prioritizing British interests and avoiding actions that could disrupt relations with either the Union or the Confederacy. The neutrality policy pursued by Palmerston was influenced by the efforts of Charles Francis Adams, the United States Minister to the United Kingdom, who effectively conveyed the Union's perspective and countered Confederate attempts to gain international recognition.

Gladstone believed in the principle of self-determination and viewed the Confederacy's struggle for independence as a valid cause. He saw the war as a conflict between two parties, and he argued that the British government should remain neutral and extend recognition to the Confederacy if it appeared likely to achieve independence.

Gladstone's public statements and speeches, such as his Newcastle speech in October 1862, expressed sympathy for the Confederacy and called for British recognition. His views caused controversy both in the United Kingdom and in the United States, where they were seen as potentially detrimental to the Union cause. Gladstone owned a home on Abercrombie Square in Liverpool, and was very likely a confidential member of the Southern Club.

The British government did not officially recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation. The British government, led by Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, adopted a policy of neutrality throughout the conflict and maintained trade relations with both the Union and the Confederacy. The official recognition of the Confederacy as an independent nation did not occur, largely due to diplomatic efforts by Charles Francis Adams and concerns over the potential consequences of such recognition on British trade and international relations.

Queen Victoria, the reigning monarch of the United Kingdom during the American Civil War, generally remained neutral and refrained from publicly expressing her opinions on the conflict. As the constitutional monarch, her role was largely ceremonial, and she did not have direct involvement in formulating or implementing government policies.

Queen Victoria's stance on the American Civil War was influenced by the prevailing British policy of neutrality. She, along with her husband Prince Albert, closely followed the developments of the war, but she did not publicly take sides or officially recognize the Confederacy as an independent nation.

It is worth noting that there were some instances where Queen Victoria's sympathies seemed to lean towards the Union cause. In 1861, she wrote a private letter to Charles Francis Adams, the United States Minister to the United Kingdom, expressing her hopes for a peaceful resolution to the conflict and her admiration for President Abraham Lincoln.

James Russell Lowell said, "None of our Generals, nor Grant himself, did us better or more by trying service than he [Charles Francis Adams] in his forlorn outpost in London." As we ponder strategy and battles and generals, we ought to keep in mind that Charles Francis Adams won a huge diplomatic victory of greater value than is ever described in books or articles. The battle of Antietam is usually credited with keeping England neutral, but the question is never asked why that was.

Imagine being Adams, who had to be diplomatic yet persuasive with Palmerston, an obviously arrogant and racist man who made decisions purely on the basis of value to his personal political future. Imagine being able to converse directly with Queen Victoria, the most powerful monarch in Europe, in such a convincing manner as to maintain her views, despite a government whose leaders tended the opposite way. The struggle to keep Palmerston and Gladstone officially neutral despite their evident slant toward the South required someone of experience, who could play the “long game”, and who could unemotionally remind these headstrong men of the consequences of choosing the wrong side. Lincoln needed a man whom the British would immediately take seriously; Adams had his family background (both his father and his grandfather had been Ambassadors to the Court of St. James as well) and the recognition of non-political accomplishments to bolster the power of his argument. And, he had had the taste of failure and frustration in his life, and knew that calmness and composure, not superciliousness, was the right path.

After the War

Minister Adams publicly supported moderation toward the South during the last year of the war and at the start of the Andrew Johnson administration after Lincoln's assassination. The British recognized him as a steady hand at the wheel. But support for Johnson's conciliatory policies, particularly his opposition to radical reconstruction of the South, was unpopular at home, and this injured Charles's future political prospects. He gladly resigned his post in 1868 with the election of the new Grant administration and returned to his home in Quincy. He turned down an offer to be president of Harvard.

But in 1871-1872 he returned to Europe with his youngest son Brooks. There, he would win his biggest victory, one that all of the frustrations and setbacks in life he had experienced, all of the diplomatic skills he had acquired, had prepared him for; and no other American of his era could have accomplished it.

As Minister to Great Britain, Adams was quite aware that although the British government was officially neutral, its citizens were taking sides anyway. And that those who supported the South, like the Southern Club, were having critical effects on the war. In particular, he knew exactly how Confederate agents were working to arrange armament shipments through the blockade. He knew that Liverpool shipbuilders were creating commerce raiders and blockade runners. He uncovered how ships were being built on the Mersey, sent off to the Caribbean under the British flag, then its crew & captain changed in port and the ship was renamed as a Confederate ship.

For example, he convinced British authorities to confiscate two ironclad warships from the Laird shipyards that were destined for use by the Confederates. But many others he could merely document. He wrote myriad letters to Secretary of State Seward with documentation of the British private sector working with the Confederacy while the official government looked the other way.

The Alabama Claims

Adams and his staff at the Embassy, including his son, collected details on the shipbuilding issue, showing how warships built for the Confederacy caused widespread damage to the American merchant marine. They documented everything in real-time: Who were the agents, where the money came from, who the British citizens were, everything. For the 4 years of the war, he collected the evidence, knowing the British weren’t going to do anything about it, and if he mentioned it, it would be a serious impediment to working with those he had to keep neutral. And so, he waited. He held onto all of these documents and they collected dust.

When Palmerston died in late 1865, Benjamin Disraeli, who for his own political purposes had no interest in getting involved after the war, took his place. Disraeli had maintained a truly neutral position during the war, but he did criticize the Lincoln administration's handling of the war and expressed concerns about the potential growth of American power if the Union were to emerge victorious. He believed that a strong United States could pose a challenge to British interests in the future. Overall, Disraeli's approach during the American Civil War was one of caution and pragmatism, focusing on preserving British neutrality and safeguarding British interests. And so, Adams held onto his notes.

The evidence he collected became the basis of the postwar Alabama Claims. The Alabama Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the government of the United States from the United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon Union merchant ships by Confederate Navy commerce raiders built in British shipyards during the American Civil War. The claims focused chiefly on the most famous of these raiders, the CSS Alabama, which took more than sixty prizes before she was sunk off the French coast in 1864.

The Alabama Claims were a series of diplomatic negotiations and arbitration proceedings that took place in the aftermath of the American Civil War between the United States and the United Kingdom. The claims arose from the actions of Confederate warships that were built and equipped in British shipyards and subsequently attacked and destroyed American ships during the Civil War.

The most notorious of these Confederate warships was the CSS Alabama, a powerful raider that had a significant impact on Union shipping during the war. The British government's involvement in the construction and outfitting of the CSS Alabama and other Confederate vessels raised serious issues of international law and neutrality. Can a country declare itself neutral but its citizens aid one of the combatants?

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, the United States sought compensation from Britain for the damages caused by these Confederate warships and demanded that the British government take responsibility for its role in aiding the Confederacy. Negotiations between the United States and Britain began in 1866, but they failed to reach a satisfactory resolution.

The United States claimed direct and collateral damage against Great Britain. The United States claimed that Britain had violated neutrality by allowing five warships to be constructed, most especially the CSS Alabama, knowing that it would eventually enter into naval service with the Confederacy. For 3 years, the British denied responsibility. They claimed that officially declaring neutrality had nothing to do with businesses its private industry conducted. They said that there was no proof of American claims. American outrage grew; Sumner, still head of the US Foreign Affairs committee, demanded $2 billion in indirect costs for supplying the South through the blockade. Calls for annexation of Canada, or provinces like British Columbia, as payment for damages became common American political rhetoric. Britain continued to stall, and Canadian separatists began looking into joining the US to control the northwest Pacific Ocean.

As a result, the United States brought the case before an international tribunal known as the Alabama Claims Commission. The evidence leading to the settlement of the Alabama Claims case was collected and presented by the United States government. After the American Civil War, the U.S. State Department was responsible for compiling the evidence of British involvement in the construction and outfitting of Confederate warships, particularly the CSS Alabama and other raiders. The U.S. government conducted thorough investigations and collected documentation, testimonies, and other evidence related to British shipyards, contractors, and individuals involved in supplying arms and vessels to the Confederate Navy. This evidence was used to support the United States claims that Britain had violated its duty of neutrality during the Civil War and should be held responsible for the damages caused by the Confederate warships.

During the negotiations and arbitration proceedings, the U.S. delegation, led by chief U.S. arbiter Charles Francis Adams and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, presented this evidence to the international tribunal, known as the Alabama Claims Commission, which convened in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1871. The evidence played a crucial role in convincing the tribunal of Britain's culpability, ultimately leading to the commission's ruling in favor of the United States and the subsequent settlement of the Alabama Claims case.

Charles Francis Adams played a crucial role in collecting the evidence for the Alabama Claims case. As the U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom during the American Civil War, Adams was responsible for gathering and presenting evidence of British involvement in the construction and outfitting of Confederate warships, particularly the CSS Alabama and other raiders. The evidence collected by Charles Francis Adams was the central documentation evaluated during the arbitration proceedings. Adams had diligently collected documentation, testimonies, and other evidence related to British shipyards, contractors, and individuals who were involved in supplying arms and vessels to the Confederate Navy. His efforts were instrumental in building a strong case against Britain, showing that the British government had violated its duty of neutrality during the Civil War.

Finally, in 1871, the British agreed to a commission to resolve the dispute, and Adams unveiled the notes and documents he had collected. He showed contemporaneous notes and letters. He named names. He had the proof, because the whole time he was ambassador, he kept meticulous records and documented everything.

The commission, which convened in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1871, was composed of representatives from the United States, Britain, Italy, Switzerland, and Brazil. After a thorough examination of the evidence and arguments presented by both sides, the tribunal issued its decision in September 1872. The tribunal ruled in favor of the United States, stating that Britain had indeed violated its duty of neutrality during the Civil War by allowing the construction of Confederate warships in its shipyards. As a result of the ruling, Britain was required to pay the United States $15.5 million in damages. Today, that would be equivalent to several hundred million dollars. Nothing like that had ever happened before.

So, who actually paid for the Confederate war machine, war supplies, and naval presence? The British Government did in 1872, along with its citizens and investors who purchased Confederate Cotton Bonds. The evidence Adams had collected during his years as ambassador played a vital role in convincing the tribunal of Britain's culpability, ultimately leading to the commission's ruling in favor of the United States and the subsequent settlement of the Alabama Claims case.

The resolution of the Alabama Claims case marked an important moment in the development of international law and the peaceful settlement of disputes between nations. It also helped improve relations between the United States and Britain after a period of tension and served as a precedent for future international arbitration cases.

Treaty of Washington

A final deal was then arranged. The Treaty of Washington established for the first time a codification of international law and of international arbitration. The Treaty of Washington resolved fishing disputes with the establishment of the Halifax Commission, set up the Alabama Claim arbitration, and set up the San Juan Island territorial dispute arbitration. The Halifax Commission would order the US to pay the UK $5.5 Mil for illegal fishing practices. The Alabama Claims would order the UK to pay the US $15.5 Mil in direct damages, with $1.9 Mil deducted for illegal US blockading practices during the war. An additional $500 million in loans was the biggest part of the agreement, which the US was able to take out with British banks at low-interest rates to refinance their war debt.

The treaty set principles of what neutrality between two warring factions meant:

1. That due diligence "ought to be exercised by neutral governments in exact proportion to the risks to which either of the belligerents may be exposed, from a failure to fulfill the obligations of neutrality on their part."

2. "The effects of a violation of neutrality committed by means of the construction, equipment, and armament of a vessel are not done away with by any commission which the government of the belligerent power benefited by the violation of neutrality may afterward have granted to that vessel; and the ultimate step by which the offense is completed cannot be admissible as a ground for the absolution of the neutral country, nor can the consummation of fraud become the means of establishing its innocence."

3. "The principle of extraterritoriality has been admitted into the laws of nations, not as an absolute right, but solely as a proceeding founded on the principle of courtesy and mutual deference between different nations, and therefore can never be appealed to for the protection of acts done in violation of neutrality."

And the best part of his story is that although it took many years, eventually his enemies were defeated, and his inherent refinement and intellect ultimately carried the battle. These setbacks that would have buried a lesser man had a funny way of moving him into his real calling. It’s kind of like a real-life “David Copperfield”, overcoming personal losses led to amazing success, albeit not exactly what anyone had imagined. His wife Abigail steadfastly supported him through all of his life’s trials. They succeeded in "passing the torch" to the next generation of the Adams family, which included four noteworthy sons—railroad reformer Charles Francis Adams Jr., Massachusetts politician John Quincy Adams II, celebrated writer Henry Adams, and historian Brooks Adams. His son Henry Adams would go on to become one of the first great American historians and authors. The posting influenced the younger man through the experience of wartime diplomacy and absorption in English culture. After the war, he became a political journalist who entertained America's foremost intellectuals at his homes in Washington and Boston. During his lifetime, he was best known for The History of the United States of America 1801–1817, a nine-volume work.

No, he was never elected President, like his father and his grandfather, and so he is often taught superficially as a man who failed. But his public service saved our country, documented who had assisted the enemy, and sought and obtained reparations from a foreign power for prolonging the war. He changed forever what neutrality entailed. And it turned out he was not only the right man for the job, he was in fact the only man who could have succeeded at it.

Enjoy that piece? If so, join us for free by clicking here.