The Western Front of World War I conjures up images of trenches, bunkers, and an artillery scarred no-man’s-land. On one side was the German Empire, on the other was France, the British Empire, and, eventually, the United States. It has long been forgotten that there was another Allied nation that fought in the trenches of Northern France and Flanders. Two divisions of the Portuguese Army fought in the British sector of the line from April 1917 to April 1918. This is not even to mention the equally large number of troops sent to fight in Angola and Mozambique against German colonial troops. Tens of thousands of Portuguese soldiers would serve in the trenches of northern Europe and in Africa. They would fight in major battles, and yet the role of Portugal in World War I is generally not acknowledged or understood.

Matt Lowe explains.

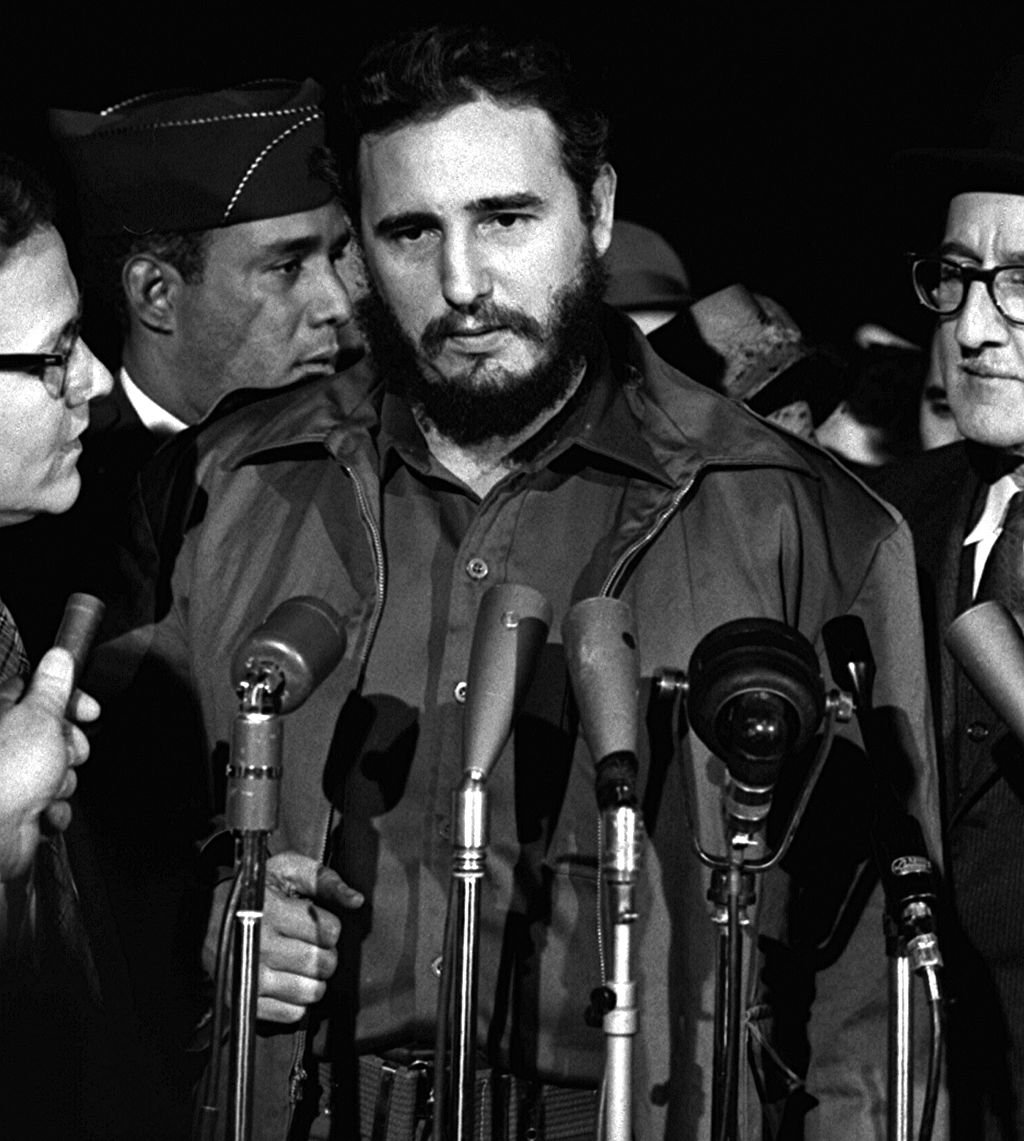

Portuguese troops going to Angola during World War I.

Revolution and a New Republic

On October 5, 1910, the Kingdom of Portugal ceased to exist. A republic was established in its place, one of only a handful in Europe. The Portuguese monarchy had been gradually weakening for decades, with numerous incidents highlighting its shortcomings at home and abroad. Notably, a disagreement over colonial boundaries in southern Africa in 1890 led to diplomatic humiliation at the hands of Britain, Portugal’s oldest ally. On February 1, 1908, King Carlos I and his heir Luis Filipe were assassinated by militant republicans. The king’s second son thus ascended to the throne as Manuel II at only 18 years of age. The monarchy was on its last legs by this point, and it was Manuel’s poor fortune to reign during such turbulent times. When the revolution finally came two years later, Manuel was forced into exile in Great Britain. A devout Portuguese patriot until his death in 1932, he would never return to his homeland. Unsurprisingly, the new republic proved to be politically unstable with a revolving door of governments over the next several years. Many Portuguese politicians wanted to prove to the rest of Europe that Portugal was no longer a political and cultural backwater. When war broke out across the continent in 1914, there was finally an opportunity to show the world that the republic was strong and that Portugal had entered the modern age politically and militarily.

A Global Conflict Begins

When the First World War began on July 28, 1914, a series of alliances rapidly brought most of the

European great powers into conflict with one another. Although Portugal did not formally join the war at this point, the war came on its own to the Portuguese colony of Angola. German South West Africa (modern day Namibia) lay directly south of Angola, and it became a battlefield as soon as news of the outbreak of war reached it from Europe. South Africa, a major British possession, had around 40,000 troops stationed there, a much larger military force at its disposal than the roughly 3,000 men of the Schutztruppe plus lower quality militia in German territory. The fighting in German South West Africa would take place mostly in the southmost parts of the colony against South African forces. Notably, however, the German military commanders in the region learned that a Portuguese expedition was being sent near the southern Angolan border. This combined with the knowledge that Portugal was Britain’s ally made them believe that this was going to lead to a Portuguese invasion from the north in conjunction with the British one in the south. Thus, the German commanders decided to send a portion of their forces to the north to launch a preemptive strike against the incoming Portuguese expedition before it could do the same to them. What they did not know, was that Portugal had no intention at the time to do anything of the sort, with the expedition’s primary role being to secure the border from German incursions and local rebel activity.

Portuguese metropolitan and colonial troops had seen intermittent fighting in southern Angola for decades and there was a fear that the war could spillover into Portuguese territory and potentially ignite a new wave of fighting. The German decision to attack was therefore almost a self-fulfilling prophecy of bringing Portugal into the war. Starting in October of 1914, a series of small battles were fought in southern Angola, most of which were won by the better trained German forces. Virtually all of these skirmishes were too small to ever be given names by either side’s historical records. The largest battle occurred on December 18 at a town called Naulila near the border, which ended in a hard-fought German victory and involved around 1500 Portuguese and 600 German troops. Ultimately, the Germans were able to occupy parts of southern Angola until July 1915, before withdrawing as the rest of South West Africa began to collapse and surrender to South African forces. As the Portuguese government predicted, there was an uptick in local rebel activity in southern Angola after it was re-occupied by Portuguese troops, due in part to the Germans distributing weapons to such groups in an effort to destabilize the region. Still, Portugal chose not to formally join the war, because, as of yet, there was more to be gained by using its neutrality to keep it safe while aiding Britain in more indirect ways.

Portugal’s Strategic Situation and Entry into the War

In spite of the 500-year-old alliance between Portugal and the United Kingdom, Portugal itself did not immediately join the war. This was largely at the insistence of the British government, as it viewed neutral Portuguese ports and shipping as more valuable assets than Portuguese troops on the battlefield. The British had a long history of exploiting its weaker ally, and the first half of World War I was merely a continuance of this trend. Between the revolution in 1910 and its formally joining the war in 1916, Portugal experienced a rapid succession of short-lived governments of different persuasions, although they were all pro-republic, they differed on their stances on formally joining the war. One of the reasons various Portuguese leaders at the time favored joining the war was to use it as a way to legitimize the republic to the rest of the world as it would fight against the arch conservative Central Powers and show that Portugal was no longer some culturally backward relic. As mentioned above, there was also a very real concern about maintaining security further from home in the African colonies. In spite of these motivations, it was not seen as being overall beneficial to fight and Great Britain exerted its not-so-subtle influence on the country. The ports of Lisbon and Porto were of great strategic value, while the Portuguese armed forces were of dubious quality at best. British diplomats knew the Portuguese would not act without the approval of the United Kingdom, and thus kept Portugal on a short leash. With Portugal officially neutral but decidedly oriented towards British interests, the United Kingdom would reap the most benefits without needing to invest many of its own resources.

This could not remain the situation, however, as the war continued to consume more and more British lives, material, and money. Most importantly, British merchant ship losses were constantly increasing. The neutral Portuguese ports offered a unique opportunity. There were dozens of German merchant vessels that had anchored in Portuguese waters early on in the war to avoid being captured by the Royal Navy. The British government made a formal request to the Portuguese Republic to confiscate these ships and hand them over for British use. Portuguese leaders had been waiting for this request and proceeded to take control of the German ships on February 24, 1916. Germany was understandably upset at this sudden violation of supposed neutrality and went on to declare war on Portugal on March 9. Portugal was now at war, although it would be several months until Portuguese troops would see combat in Mozambique and over a year until they would see combat on the Western Front.

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps Arrives in France

The declaration of war from Germany did not translate into the immediate sending of Portuguese troops to the Western Front. Although Portuguese leaders had been seeking this outcome and the army had been mobilized since 1914, it would still take time before the necessary units could be gathered and trained sufficiently. The British, French, and Portuguese planners met to hammer out the details for how the Portuguese army would be equipped and where it would be stationed on the front. Ultimately, it was decided that the Portuguese would fight alongside the British in Northern France and Flanders. The infantry would be supplied with British arms and equipment to ease logistical concerns. A separate artillery unit would be supplied by the British as well, but it would operate under French command in a different sector. The first Portuguese troops landed in France on February 2, 1917, nearly eleven months after formally entering the war. After further training and equipping, the first units of the Corpo Expedicionário Português (CEP) would take their places in the front lines on April 3. Over the following year, the CEP would grow to two divisions with a total of 55,000 men, initially under the command of General Fernando Tamagnini de Abreu.

The section of the front the Portuguese occupied was relatively quiet. This was on purpose as it allowed the British pull out two of its divisions to use elsewhere. That is not to say that the sector was safe or inactive, however. The first Portuguese fatality on the Western Front was António Gonçalves Curado, who was killed by mortar fire on April 4. Portuguese troops treated their assignments seriously and sought out opportunities to take the fight to the Germans. The Portuguese patrolled often and conducted trench raids to capture prisoners and gather intelligence on enemy displacements. Throughout the rest of 1917 and first months of 1918, the Portuguese proved to be competent soldiers when trained and equipped properly. The primary problems that would torment the CEP, however, came from back home. Political instability had become the norm, and a de facto military junta came to power when army officer Sidónio Pais became prime minister in December 1917. In spite of the army having immense political influence, public opinion had never been strongly in favor of joining the war in the first place, and each successive government (including the junta) found it easier to ignore the problems that come with organizing and supplying a military campaign far from home. Over time, reinforcements began to dwindle, and the amount of time units spent at the front grew to ridiculous lengths. Whereas their British counterparts would cycle in and out of the front line trenches every few weeks, Portuguese soldiers had to stay for months at a time. The Portuguese logistical situation was poor and there were simply not enough spare men to go around. For their part, the British did very little to help and did not offer to replace the CEP in the line to allow for rest and refitting until spring 1918. The timing could not have been worse, because the battle that was coming would prove catastrophic for the British and the Portuguese especially.

East African Campaign

Meanwhile, the war was also being fought thousands of miles away in East Africa. German East Africa (modern day Tanzania) had been the location of major fighting since the war began, and by the time the Portuguese had formally joined the war, the German troops in the colony had begun a successful guerilla campaign against the British and Belgian invaders from the neighboring colonies. Once Portugal had formally joined the war in 1916, it sent an expedition of 4,500 metropolitan troops to Mozambique in July to shore up the colonial garrison of around 5,000 African askaris. Minor efforts were made to cross the southern border of German East Africa by Portuguese troops, but these were unsuccessful. By September of that year, the Germans had been pushed to the southern third of their colony by British and Belgian advances from the north and west respectively. At the forceful encouragement of the politicians back in Lisbon to take a more active role in the campaign, Portuguese troops launched a larger attack across the Rovuma River into the German colony. After some initial success, this attack too was pushed back across the border in October. The border area between the Portuguese and German colonies remained relatively quiet for a year. Portuguese leaders were doubtful of the value of their African colonial units and instead relied disproportionately on the metropolitan units sent all the way from Portugal. In fact, Portugal was the only country involved in the East African campaign to send significant numbers of European troops to the region. Regardless of where the Portuguese troops originated from, the German-led colonial units proved to be more effective than virtually all of the Portuguese units that fought against them. After the failed offensive, another expedition was sent from Portugal to reinforce their depleted units during the first half of 1917.

As the Allies in the north continued to press the Germans into a smaller pocket of their colony, the German commander Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck decided to invade Mozambique to acquire supplies and some breathing space for his troops. In late November 1917, the Germans attacked across the Rovuma and routed the Portuguese defenders for very few losses. With few exceptions, the Portuguese faired very poorly and the Germans captured vast quantities of food supplies, clothing, and weapons that they would put to good use for the rest of the war. British-led troops were landed on the northern coast of Mozambique to reinforce their Portuguese allies, but this only partially stabilized the situation. Von Lettow-Vorbeck’s forces remained at large in Mozambique until late September 1918 when they crossed back into German East Africa and then on into Northern Rhodesia (modern day Zambia). The war ended a month and a half later with the German forces in East Africa being the last Central Powers troops to surrender on November 25, 1918. The Portuguese performance during the East African campaign was their worst showing of the war. Poor leadership, insufficient training, low morale, and ill health all contributed. The only territorial gain awarded to Portugal for its participation in the war was the Kionga Triangle at the mouth of the Rovuma River. It was a small, economically insignificant area of muddy land that seems to be symbolic of Portugal’s poor fortunes during the campaign.

The German Spring Offensives and the Battle of the Lys

On March 21, 1918, the first phase of the German Spring Offensives began, with the primary aims of pushing the British army back towards the sea and gaining a stronger position before the arrival of significant American forces on the front could tip the balance in the Allies’ favor permanently. The Lys Offensive, or Operation Georgette, would be the second major effort of the offensives, and focused on the Franco-Belgian border area. By April 1918, the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the CEP had been at the front without break for nine and five months respectively. The 1st Division had been scheduled to start cycling out of the line in March, but the German attacks further south delayed this for nearly three weeks. The 1st Division was finally pulled out of the line on April 6, but it was not replaced by any British units. This left the 2nd Division to spread itself thin to cover several miles of the front lines by itself in the meantime. Three days later, on April 9, Operation Georgette began. Twelve German divisions attacked the weakest sector of the line, that was held by the Portuguese 2nd Division and the British 40th Division. The Germans had not specifically targeted the sector because it was held by the Portuguese, but they could not have picked a better time to take advantage of its particularly weak disposition. The British and Portuguese units in the area fought back as hard as they could but were quickly overrun and those that could began to retreat. That day thousands of Portuguese soldiers were either killed or captured and, after a year of frontline operations, the CEP had effectively ceased to exist as a unified fighting force.

Although the German Spring Offensives of 1918 were ultimately unsuccessful, they did provide a severe shock to the Allies and showed that the German army would be a very difficult opponent in the coming months. The entire British line had been defeated during the early days of Operation Georgette, and the generals looked for a reason. A convenient scapegoat was found in their Portuguese allies. False claims were made that the Portuguese troops had fled without fighting and left the British units on their flanks dangerously exposed. This had not been the case, and, if anything, the Portuguese had fought as hard as any of the men that were unfortunate enough to be at the front that day. Unfortunately, the British unit histories from the time maintained the narrative that the Portuguese had shamefully faltered and condemned their allies to an ignominious defeat. The fact is that the CEP had been neglected by its government at home and its allies at the front. There was no lack of courage in the average Portuguese soldier, but this can only go so far. It was inevitable that they would not be able to hold in the event of a major attack. The Portuguese army, although still based in France, would not contribute any significant forces to frontline operations for the remainder of the war.

Conclusion

History has not been kind to the fighting men of Portugal during World War I. The memory of their exploits, limited as it is, has been defined by their failures. The burden of the most spectacular of these failures, as previously described, was unduly placed on the CEP in order to save the reputation of a supposed ally. The fact of the matter is that the Portuguese contribution to the First World War was a mixed bag. Its performance in the African theaters was mediocre at best and shambolic at worst. The performance of the CEP on the Western Front, however, was of a much higher quality. In spite of the considerable failings of the British and Portuguese leadership, the CEP was generally better led, equipped, and motivated than their countrymen further afield. Over the course of a year, the Portuguese soldiers in northern France proved that they were perfectly capable of fighting in the full complexities and horrors of modern warfare. The CEP was in the wrong place at the wrong time and has paid for this unfortunate circumstance for over a century. Overall, Portugal lost approximately 8,700 European and colonial troops during the war: 657 in Angola, 2,103 in France, and 5,961 in Mozambique (mostly due to illness). One can only hope that the legacy of the Portuguese war effort can be rehabilitated now that it is clear that its poor reputation was largely manufactured by British historians during and immediately after the war. Today, there are a handful of solemn reminders of the sacrifice of the Portuguese soldiers. Most, of course, are located in various cities throughout Portugal. There are two, however, in France. One is a memorial sculpture outside the Catholic church in the town of La Couture in northern France, not far from the Belgian border. The other is located in the nearby town of Richebourg. Here is the Portuguese Military Cemetery, where almost 2,000 Portuguese soldiers are buried. Although these sites are small compared to the many other Great War monuments scattered throughout the region, they at least offer a quiet dignity to the men so long maligned and forgotten.

What do you think of the role of Portugal in World War I? Let us know below.

Now read about Portugal during World War II here.

References

Abbott, Peter. “Armies in East Africa 1914-18.” Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, 2002.

Barroso, Luís. “A Primeira Guerra Mundial em Angola: O Ataque Preemptivo a Naulila.” Relações Internacionais, September 2015, pp. 127-148. http://www.ipri.pt/images/publicacoes/revista_ri/pdf/ri47/n47a07.pdf

Duarte, António Paulo, and Bruno Cardoso Reis. “O Debate Historiográfico sobre a Grande Guerra de 1914-1918.” Nação e Defesa, 2014, pp. 100-122. https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/17732/1/ICS_BCReis_Defesa_ARN.pdf

Pyles, Jesse. “The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: From Inception to Combat Destruction, 1914-1918.” University of North Texas, May 2012. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc115143/m2/1/high_res_d/thesis.pdf

Tavares, João Moreira. “War Losses (Portugal).” 1914-1918 Online, April 2020. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/pdf/1914-1918-Online-war_losses_portugal-2020-04-20.pdf