Neville Chamberlain will without a doubt continue to be a controversial figure in British history. His tenure as a British Prime Minister will be always overshadowed by his last seven months in that position as German forces swept across France and Belgium forcing the British and French evacuation from Dunkirk. His appeasement policy has been portrayed as a weak and ineffective Prime Minister who sold out to Hitler. This perspective has been allowed to stand as the defining feature of his career but there was more to Chamberlain than his appeasement policy and the disaster that ensued.

Steve Prout looks at Neville Chamberlain’s career.

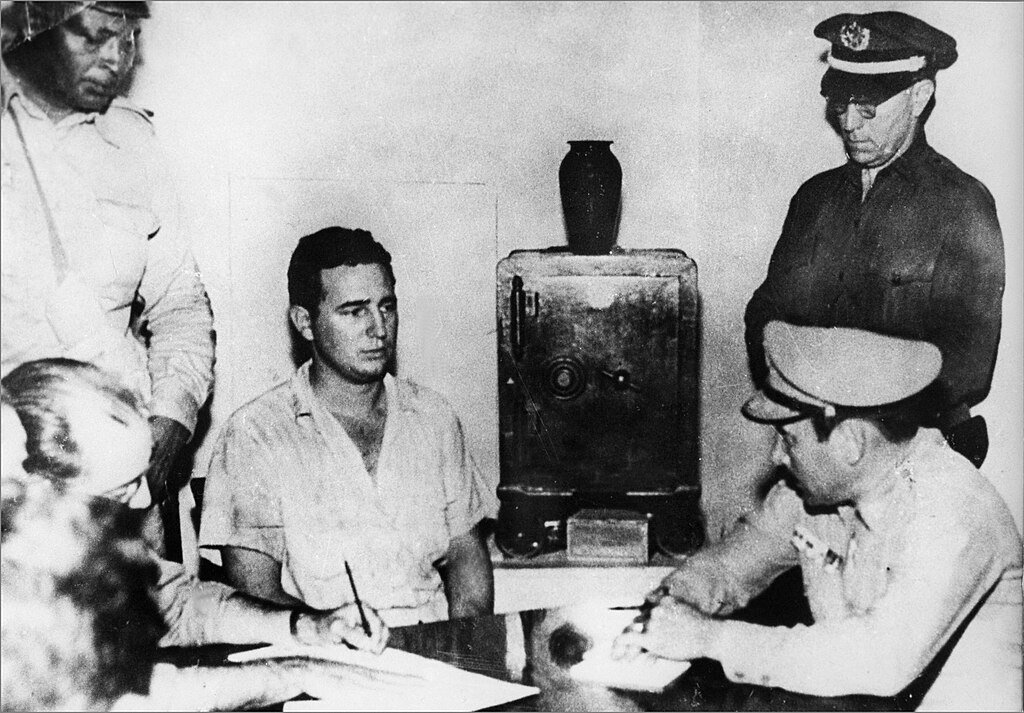

Neville Chamberlain holding the signed Munich Agreement in 1938 after meeting Hitler. The agreement committed to peaceful methods.

Lloyd George and the First World War

Chamberlain first started out in life as a successful businessperson before serving as the Lord Mayor of Birmingham between 1914-16. Afterwards he took the post as Director-General of National Service during the First World War under David Lloyd George. It would not be a successful start in his political career because he was often at odds with Lloyd George who was particularly critical of Chamberlains’ techniques. Chamberlains and his supporters would argue that he frequently lacked the support and clarity needed from Lloyd George to be successful in that role.

Both would harbour mutual dislike of each other that would continue up to Chamberlains death. Lloyd George would state that Chamberlain was “not one of my most successful selections” and in later added, ‘When I saw that pinhead, I said to myself, he won’t be of any use.’ Chamberlain in return referred to Lloyd George as "that dirty little Welsh Attorney.” Suffice to say it was a relationship that would never repair and resurface much later at when Chamberlain was at his most vulnerable.

Not all of Chamberlain’s peers agreed with Lloyd George’s comments. John Dillon, an Irish Nationalist MP, stated in a rather flowery fashion that "if Mr. Chamberlain were an archangel, or if he were Hindenburg and Bismarck and all the great men of the world rolled into one, his task would be wholly beyond his powers". Bonar Law in a more succinct manner called Chamberlain’s role an "absolutely impossible task" and would later rescue Chamberlain’s career. Meanwhile Chamberlain's successor Auckland Geddes received more favor and support than Chamberlain ever received.

In 1918 when Chamberlain became a Member of Parliament he refused to serve under Lloyd George and in 1920 he refused a junior appointment offered by Andrew Bonar Law in the Ministry of Health. In October 1922, the situation changed when Lloyd George’s Coalition Government collapsed and presented Chamberlain new opportunities and a succession of top-level posts would follow.

Despite Lloyd George’s disparaging comments Bonar-Law was impressed with Chamberlain’s administerial abilities and appointed him as Postmaster-General. A promotion to Minister of Health in March 1923 soon followed and his advancement would continue. In August 1923 Bonar Law was forced to resign due to his ill health and Stanley Baldwin who took over as Prime Minister appointed Chamberlain as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

His ascent to the top levels of government was as fast as it was brief. Within five months Baldwins Conservative government was defeated in the December 1923 general election and the first Labour government took power in January 1924. Chamberlain’s contribution almost went unnoticed, but renowned historian AJP Taylor said of Chamberlain “nearly all of the domestic achievements of Conservative governments between the wars stand to his credit.” The work he did in the interwar years was considerable.

Domestic affairs – politics in the interwar period

Neville Chamberlain was highly active in all the offices he held. He possessed a drive to reform and promote efficiency. By 1929 he had presented twenty-five bills to Parliament of which twenty-one of this number had become enacted into law and practice. Despite this Opinion remains divided concerning Chamberlains effectiveness as politician and Prime Minister. His achievements were numerous.

The introduction of the Local Government Act of 1929 abolished and reformed the obsolete poor laws in Britain that were not fit for purpose. The administration of poverty relief was placed in the hands of local authorities. One aspect of this act made medical treatment of the infirmaries free to those who could not afford it. In a pre-1945 Welfare State Britain this was a forward-thinking piece of legislation.

The Housing Act in 1922 addressed another set of issues. The necessity for this piece of legislation arose due to the shortfall in housing created by the previous Liberal Government, who under Christopher Addison had promised “homes fit for heroes” for the returning soldiers but the reality was that this promise had not delivered upon. Chamberlain was tasked to address this shortfall. He was of the belief that Government high subsides were the reason building costs were remaining too high and so stunted progress. Being a former businessperson and quintessential conservative, he believed the private building sector would perform the task more efficiently and so reduced these subsides. He was not entirely wrong because by 1929 438,000 houses were built. This was in the words chosen by AJP Taylor’s “the one solid work of this (Baldwins) dull government.” But critics viewed the Housing Act as only helping the lower middle classes and not the industrial workers giving the impression that he was the “enemy of the poor”. This perception would contribute to losing the Conservatives a substantial number of votes.

The introduction of the Widows', Orphans' and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act 1925 lowered the age for entitlement to receive the old age state pension from 70 to 65 (there has been little change since until the twenty first century), and it allowed provisions for dependents of deceased workers. Although it was met with criticism for not extending far enough it was still nevertheless a progressive step forward for pre-welfare state Britain. Chamberlain’s justification to his critics was that the act was not intended to replace private thrift and that the sum was the” maximum financially feasible” within budgetary means.

The Factory Act of 1937 was another successful and progressive piece of legislation for the time. Whether the motive out of altruistic reasons or due to a growing, effective opposition from the Labour Party and the unions it still was particularly far reaching. This Act set various standards factory working condition which addressed working hours, sanitation, lighting, and ventilation. This had significantly improved working conditions set by an earlier Act in 1901. The official wording by the Home Office, signed by Samuel Hoare was that the act presented an “important milestone on the road to safety, health and welfare in Industry.” The Holiday Pay Act of 1938 would follow which allowed workers one full week’s holiday pay. By modern times this seems paltry, but in the context of the time it was a significant move forward for the working population.

Chamberlain had his supporters although much of this support came posthumously. AJP Taylor said that “Chamberlain did more to improve local government while serving as Health Minister than did anyone else in the 20th century” and from an American perspective, according to Bentley Gilbert, Chamberlain was "the most successful social reformer in the seventeen years between 1922 and 1939… after 1922 no one else is really of any significance."

Dutton considers, later in 2001, that Chamberlain's accomplishments at the Ministry of Health were "considerable achievements by any standards" and of Chamberlain himself “a man who was throughout his life on the progressive left of the Conservative Party, a committed believer in social progress and in the power of government at both the national and local level, to do good” - but the war clouds that were gathering above Europe and his domestic achievements would be forgotten.

Munich, Churchill, and the road to war

In his last few months as Prime Minister Chamberlain and his appeasement policy was attacked from his own party and opposition parties with accusations of being blinkered, narrow and supporters of appeasement were now labelled cowards whereas before they were saviours for averting war. This is not entirely fair as for Chamberlain’s government these were not normal times and the problems placed before his government left his few alternatives that sat comfortable or palatable with little or no alternative but to acquiesce to Hitler’s demands.

Chamberlain’s bellicose opponents were either suffering from a delusion that Britain could face the many growing threats abroad alone. There were no suitable allies to form effective alliances with, the USSR was as untrustworthy as Germany, and therefore any containment from the east for the time being was unlikely. There were other threats outside of Europe such as Japan which threatened Britain in the Asia. The USA, a power in the Pacific, was following an isolationist policy. Adding to this were Italian aspirations for empire building in North Africa, and there Britain needed a cautious approach.

Churchill would ignore all of this, re-write history, and instead portray Chamberlain in a poor light whilst at the same flattering his own place in history. On the one hand he said “I have received a great deal of help from Chamberlain. His kindness and courtesy to me in our new relations have touched me. I have joined hands with him and must act with perfect loyalty.” Then on the other hand he said "Poor Neville will come badly out of history. I know, I will write that history" and he ensured that this happened in his memoirs, The Gathering Storm, in 1948 by referring to Chamberlain as “an upright, competent, well-meaning man fatally handicapped by a deluded self-confidence which compounded an already debilitating lack of both vision and diplomatic experience”.

For many years, his version of events remained unchallenged, but we wonder how much of this can be taken as a gospel of those times. We forget that whereas Chamberlain sought to work with Hitler and was later reviled for doing so, Churchill had no qualms with working with other dictators as we would see for example with Stalin in 1941 and in the 1930s his praise of Mussolini. Stalin’s relationship with the democracies would prove equally toxic. After the war Eastern Europe would be subjected to further totalitarian rule which would last longer than Hitler’s domination of Europe.

Chamberlain was not fooled by the outcome of Munich affair, and he knew by that point in time that Hitler could not be contained nor trusted. He immediately started in earnest an ambitious rearmament programme. This programme was on no small scale and challenges the accusations of complacency that history critics accuse him of. In May 1938 after four months elapsing since Munich agreement, Chamberlain told the annual Conservative Women’s Conference that “we have to make ourselves so strong that it will not be worthwhile for anyone to attempt to attack us”.

Rearmament

Chamberlain began a vast expansion in Britain’s armed services. Whilst doing so he was attacked by the Labour Party for ‘scaremongering, disgraceful in a responsible politician’ because of his support of expansion of Britain’s military capacity. By April 1939, rearmament was swallowing 21.4 per cent of Britain’s Gross National Product, a figure that reached 51.7 per cent by 1940. War was delayed but it was to no avail to “a man of no luck.” The failure of the Norwegian campaign and the subsequent invasion of the Ardennes quickly changed the political landscape for Chamberlain, eroded the support of his own party and of the majority of as in May 1940 British troops were being evacuated off Dunkirk.

The results of Chamberlain’s rearmament programme were not immediately appreciated but the advances made in Air Power and Sonar were vital for the Battle of Britain. The British Spitfire for instance was one of the most up to date fighter planes of the time. The British expeditionary force at the time of its mobilisation was one of the most modern and mechanised armies in the world. Within the disaster of the Norway there was one redeeming feature - that naval battles crippled the German Navy so much it could not be relied upon by Hitler in his plans to invade Britain. All these subtle factors brought Britain a chance, albeit a hairs breadth, of resisting an invasion if nothing more. The realists also knew there was little chance of an offensive and Britain could only consider her meagre defensive options.

Although Chamberlain was assigned the blame for the failure to hold Norway he was not the architect of the plan. This plan was in fact devised and supported by Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty who made many unpunished errors in the matter. He had the diminished confidence of his Conservative peers owing to his costly actions in The First World War and India. Some feared that Norway would be a repeat of Gallipoli. In the debate in The House of Commons in May 1940 when questioned about the campaign Churchill said “I take complete responsibility for everything that has been done by the Admiralty, and I take my full share of the burden” only to be rebuffed by Lloyd George who vented his criticism out on Chamberlain whose fate was already sealed.

Chamberlain was not alone in his naivety that Germany was economically stretched and that a simple naval blockade would deprive her of her natural resources. Churchill even displayed lack of foresight over Germany’s strategic position when the Soviet Union invaded Poland when he immediately proclaimed, “Hitler’s Gateway the East was closed.” Under the 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Soviet Union was providing vast quantities of war materials to Germany. It was a spoken folly equal to “Hitler has missed the bus.”

The war materials the Soviet Union provided to Germany throughout the early years of the war were enough to render any Allied blockade ineffective. Whether Churchill knew the quantities and the extent is not known but it is likely that this would have been available via the British intelligence services. The true extent of the aid the Soviets gave was over 820,000 metric tons (900,000 short tons; 810,000 long tons) of oil, 1,500,000 metric tons (1,700,000 short tons; 1,500,000 long tons) of grain and 130,000 metric tons (140,000 short tons; 130,000 long tons) of manganese ore. This considerable amount of material excludes rubber and other industrial outputs that enabled Germany’s war machine. If Chamberlains political judgements were flawed then equally so were Churchills, but he was not in the Premier’s seat and so escaped much of the fallout.

Critics

Old adversaries and new would be particularly visceral in the debates that followed in parliament. It is interesting how some of Chamberlain’s most vocal and loudest critics were also the most hypocritical. Leo Amery famously quoted “You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!". Leo Amery was a supporter in the 1930s of Italian aggression in Abyssinia and Japanese ambitions in Manchuria. Lloyd George, who held a deep dislike of Chamberlain, also could not resist but he also conveniently forgot his courting of Hitler in September 1936 and his praising of a “pro-English Hitler”. Chamberlain’s premiership ended but he continued to serve in the higher levels of government until his death.

Chamberlain’s political career continued long after Munich and it was not yet over. He still served cordially under Churchill in the war cabinet. Despite the war controversy Chamberlain, in Churchill’s absence due to Prime Ministerial duties, still deputised and chaired the war cabinet meetings until cancer finally forced him to resign in 1940.

Chamberlain spoke of Churchill, “Winston has behaved with the most unimpeachable loyalty. Our relations are excellent, and I know he finds my help of terrific value to him.” Churchill reciprocated: “I have received a great deal of help from Chamberlain. His kindness and courtesy to me in our new relations have touched me. I have joined hands with him and must act with perfect loyalty.” And upon Chamberlains death he said. “What shall I do without poor Neville?,” as Churchill admitted that he “was relying on him (Chamberlain) to look after the Home Front.” Chamberlain had remarkable administrative skills Churchill recognised and still was of value to Britain’s war effort. Churchill himself admitted that the two men could work respectfully and professionally with each other.

In a eulogy in the House of Commons Churchill spoke highly in praise “He had a precision of mind and an aptitude for business which raised him far above the ordinary levels of our generation. He had a firmness of spirit which was not often elated by success, seldom downcast by failure and never swayed by panic…He met the approach of death with a steady eye. If he grieved at all, it was that he could not be a spectator to our victory, but he died with the comfort of knowing that his country had, at least, turned the corner.”

Churchill would conveniently forget this in the post war period and be one of many to blight Chamberlain's career and reputation. Dr Adam Timmins, reviewing the book Appeasing Hitler by Tim Bouverie sees that too much emphasis was put on one event and one person and no other factors that guided that decision which at the time appeared the only sensible option only hindsight offers other alternatives. Without the benefit of hindsight, the phenomena of Hitler were something that had never been witness or confronted before, and with that it is of no surprise that the states people of the 1930s failed to accurately judge him.

Conclusion

Neville Chamberlain’s presence in British history will always be overshadowed by Munich and the road to war. This will always continue to be enforced by surviving accounts such as Michael Foot’s Guilty Men or Churchill’s post war memoirs, which places the failure to contain Hitler together with the early misfortunes unfairly on his shoulders.

When we remove all of this from the emotional equation Neville Chamberlain has been unjustly criticised and maligned by political opportunists of the time who failed to understand the limitations Britain faced. Chamberlain was proof of the adage that “history is written by victors”, a phrase invented by Churchill who did just that when writing about Chamberlain. He conveniently chose to omit his own failures and ill judgement in the early days of the war. It is that context that the Director of Military Operations, Major-General J.N. Kennedy, remarked on later during the campaign in North Africa. "He (Churchill) has a very keen eye to the records of this war”, Kennedy wrote in his diary, “and perhaps unconsciously he puts himself and his actions in the most favourable light.” Churchill’s contradictions and self-aggrandization are unhelpful and misleading.

Chamberlain was the unfortunate victim of circumstances. AJP Taylor terms him a man of no luck whom the cards always ran against. He had a shaky start against Lloyd George and his humiliation at Hitler’s hands bookended his political career. The tide of the war would turn against Hitler and deliver Churchill two titanic allies with immense resources, the USA and T=the USSR, to form a formidable alliance. It was a matter of fortunate timing that Chamberlain would be denied and that Churchill would enjoy.

Chamberlain’s other work, which brought about significant and successful social reform, went unnoticed. At the outbreak of war, he said in Parliament "Everything I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins." Chamberlain’s legacy would be marred by his unwavering desire to avoid war that was further tainted and twisted by the hypocrisy of his critics. Neville Chamberlain will always be a subject of polemical debate and his reputation will continue to be blighted.

When do you think of Neville Chamberlain’s career? Let us know below.

Now read about Britain’s relationship with the European dictators during the inter-war years here.

References

Stuart Ball - Professor of Modern British History at the University of Leicester. Portrait of a Party: The Conservative Party in Britain, 1918–1945 (Oxford, 2013).

Leo McKinstry - In Defence of Neville Chamberlain – Article the Spectator Nov 2020

David Dutton – Reputations – Neville Chamberlain – May 2001 – Bloomsbury Academic

AJP Taylor English History 1914-45 and Origins of The Second World War

Graham Hughes, history graduate (BA) from St David’s University, Anglo-Nazi Alliance Debate