The Roman Dynasty ruled Russia from 1613 to 1917. Here, author Ellen Alpsten tells us of her fascination with Russian history and how she started to write her series on the Tsarinas.

Catherine I, one of the Russian Tsarinas. She was empress from 1725-27.

If ever there was a walk on the wild side, the early Romanovs in the 17th and 18th century took it. The wild and unbridled world of the Russian Baroque gives me the perfect backdrop for my novels of the ‘Tsarina’ series: epics cloaked in ice and snow, personal passions ruthlessly push on in the quest for power, resulting in the birth of the nation we know today.

My family’s stance on Russia is ambivalent – my father grew up in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), or East Germany. Forced to learn Russian he felt free to hate the Soviets. My cousin, however, runs a small, highbrow publishing house, which works with latter-day Russian intellectuals. I myself discovered this geographical behemoth and historical riddle when reading a book called ‘German and Russians’ by author Leo Sievers. It introduced me to the larger-than-life characters of Ivan the Terrible, the ‘Times of Troubles’ and finally the rulers of the young Romanov dynasty, who had been voted into office. I fell in love, head over heels, with these lives, fascinated by their uncompromising fullness.

But how to find out more about the shadowy figures that captured me the most: the women who dared to rise against the oppressing patriarchy in the world’s largest and wealthiest realm? The first century of Romanov rule was largely female-dominated. If the fact had not been ignored, research centered on Russian’s final Tsarina, Catherine the Great, who was not even a Romanov by blood, but a German Princess. Instead, I hoped to surprise and tell something new. Yet where to start?

Growing fascination

Nikita Romanov said it in 1666: ‘We are as cursed – our men are as meek as maidens, and our women as wild as wolverines.’ Dwelling deeper on such a quote did not allow for half-measures. I read voraciously, and such divers oeuvres ranging from Tolstoy, Pushkin, Gogol, and Dostoyevsky to modern sociological studies such as the deeply disturbing ‘The unwomanly face of war’ by Svetlana Alexeyevich, Biographies like ‘Young Stalin’ by Simon Sebag Montefiore and also the lost, genteel worlds of the few that came at the expense of millions in Vladimir Nabokov’s ‘Speak, Memory’. How else should a foreigner grasp a culture as complex as the Russian? My interest morphed into a passion: I watched Russian films such as ‘Battleship Potemkin’ and the experimental ‘Russian Ark’ movie. And, lucky me, there were fascinating original sources galore, such as the diary of the German merchant Adam Olearius, who visited Tsar Mikhail Romanov’s court, stunned by a people ‘hardly better than animals.’ Invaluable, too, were letters of foreigners at the Russian Court such as the British Mrs Rondeau, and reports by the Dutch ambassadors and his colleagues sent by Princes of German nationality. Rounding off things with Robert Massie’s and Henri Troyat’s biographies about Peter the Great was unavoidable. Last but not least, Professor Lindsey Hughes of the ‘London School of Slavonic Studies’ tome 'Russia in the time of Peter the Great' turned out to be my bible as I dwelled deeper and deeper into the strange, shocking, sensuous world of both Russian history and its soul. It combines seemingly insurmountable contrasts casually, a lack of compromise that is fascinating. Finally, I even read Russian myths and fairy tales, which disclose so much about the imagination of a people.

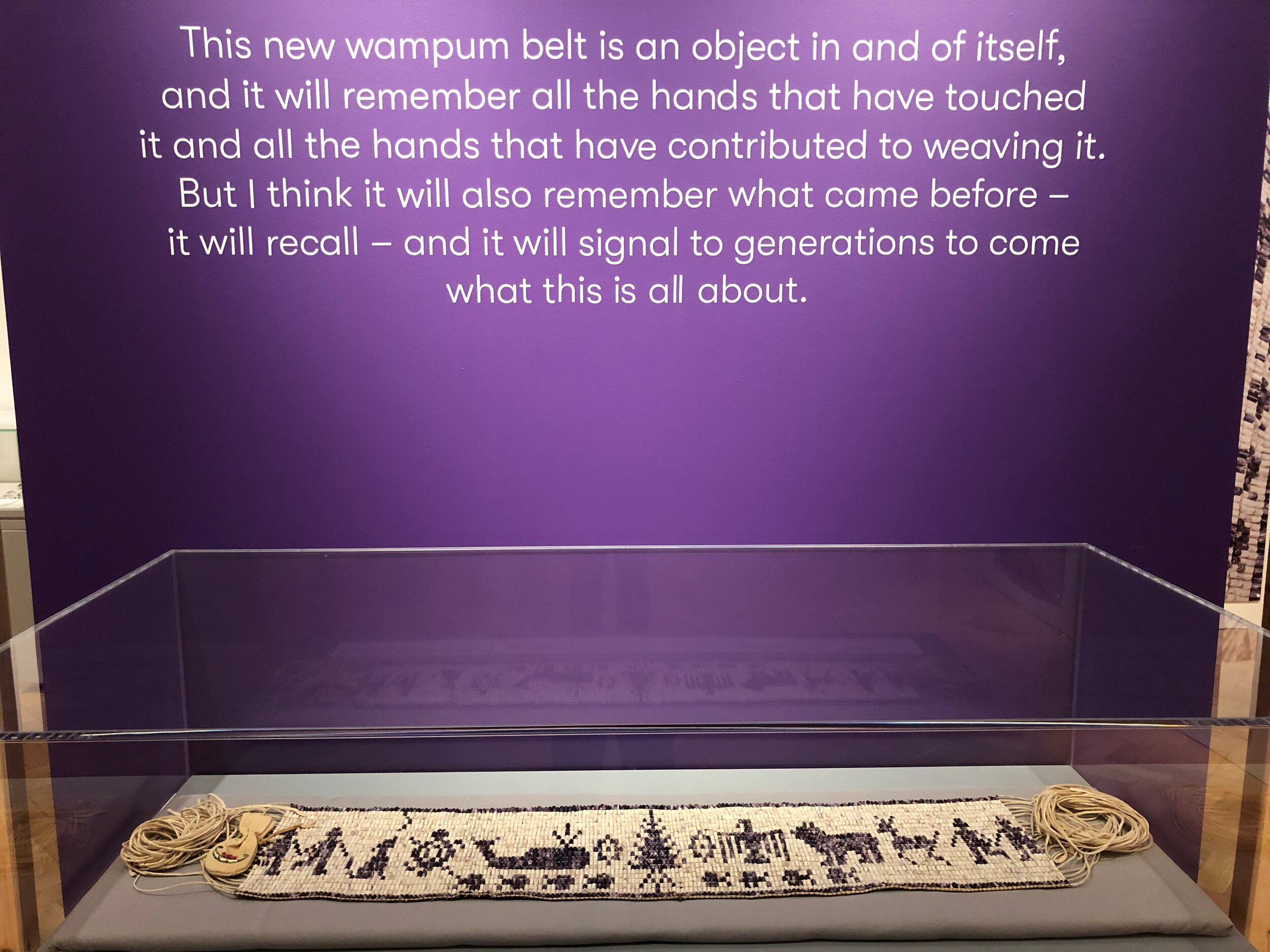

It took me a year to dare write the first word of my then debut, ‘Tsarina.’ The series is like threading a loom to weave a story as rich as any tapestry covering the walls of the Winter Palace. The novels attempt an answer to what my heroines’ lives were really like, flying in the face of a brutal patriarchy, and taking Russia from backward nation to beginnings of the modern superpower. Fleshing out those bare bones forced me to consider a myriad of aspects.

Writing

The Russians are a communal people – the word for happiness -‘shast’ye’- means being part of something bigger. Neither ‘Tsarina’ nor ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ ever surrendered to fate’s blows but made the best of a given situation. Their minds were not academically trained, they acted with courage, care and cunning, counting on people and rewarding family, friendship, and loyalty. Whatever obstacle there was to overcome, they dusted themselves off and saw another day, ready to be surprised by its gifts. This makes ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ a very modern book.

The strict framework of dates, events and details of the Russian Baroque and the Petrine era set of the beauty of my hitherto hidden historical heroines the better. If I was free to construct ‘my’ characters, every aspect had to be correct, from the clothes they wore, to the food they ate, the beliefs they held and how houses, roads, villages, carts etc. looked. As for the dramatic curve, I followed advice that the best-selling French author Benoîte Groult had once given me when I worked as her assistant: ‘To wish our hero well, the reader needs to see her/him sink low.’ Elizabeth, ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’, falls from riches to rags and rises from rags to Romanov!

After all this research I hope that nobody, who has read ‘Tsarina’ or ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’, will ever forget my heroines again; and I hope for my writing to be as raw and unafraid as their lives were. Any writer dreams of finding such unspoiled, unexploited characters as the ‘Tsarina’ series.

If an artist has a central theme to his creation, they are mine.

The Tsarina’s Daughter by Ellen Alpsten (Amazon), published by Bloomsbury, is out in hardback on July 8, and Tsarina, Ellen’s first book, is out in paperback now (Amazon US | Amazon UK).