There are only two known survivors of the April 1717 wreck of the ship the Whydah Galley, commanded by Sam Bellamy: Thomas Davis, a carpenter, and John Julian, a pilot. But were they the only two men to survive the wreck? Laura Nelson, author of The Whydah Pirates Speak (Amazon US | Amazon UK), explains this American pirate story…

A model of the ship the Whydah Galley. Source: jjsala, available here.

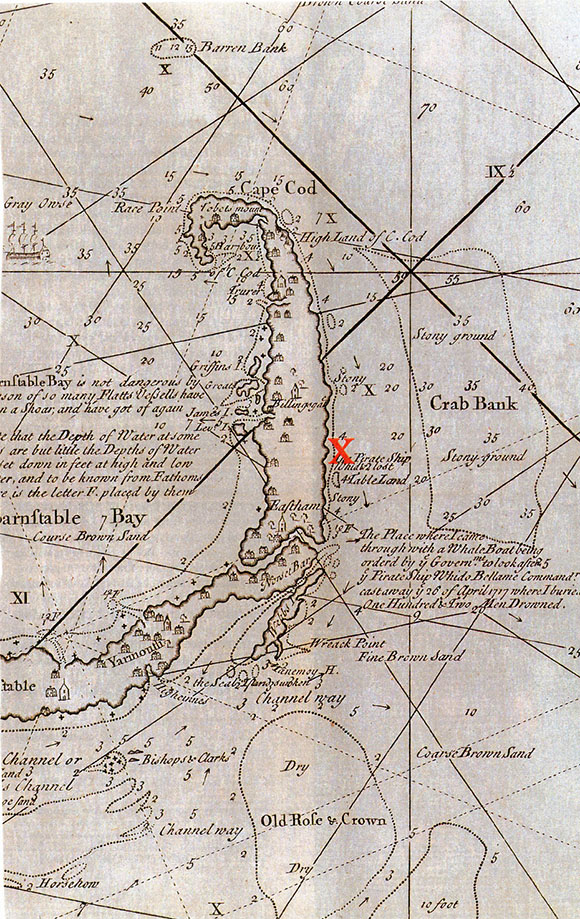

The location of the wreckage of the Whydah Galley in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, Cape Cod.

Bellamy and his crew were sailing north along the east coast of what is now the United States. Folklore says their intended destination was Eastham in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where Bellamy intended to pick up Maria Hallett, believed to be his lover, on their way to Rhode Island or Maine. He may also have been hoping to sell some of their booty…

The Storm

April 26, 1717, started out like any other day for the pirates. In the morning, they captured the Mary Anne, “a pink with more than 7,000 gallons of Madeira wine on board… and then the Fisher – a small sloop with a cargo of deer hides and tobacco” in the afternoon.[1] Per customary pirate procedure, smaller groups of pirates were sent over to these ships from the Whydah to act as the new crews of their “prizes.”

At the time of the wreck, the Whydah boasted a complement of about 150 men, all crammed into a ship that measured thirty feet wide and one hundred feet long. With the bulk of the pirates’ booty stored on the Whydah, the decks were probably starting to sag. Along with such items as “[e]lephant tusks, sugar, molasses, rum, cloth… indigo, and… dry goods…there was the precious metal, 180 sacks of coins, each… weighing fifty pounds.”[2] What this meant was the Whydah would have been very low in the water, a dangerous condition in a storm.

Throughout the afternoon a dense fog had rolled in, what should have been an early storm warning for the pirates. In the late afternoon the storm itself began. Instead of steering out to sea, Bellamy chose to stay close to the land, a move which leads many to believe he did indeed wish to try and make port somewhere in Cape Cod.

Sometime after 5pm Bellamy ordered all three ships to light lanterns on their sterns, a common navigational aid. But conditions continued to get worse.

“An arctic storm from Canada was driving into the warm air that had swept up the coast from the Caribbean. The last gasp of a frigid New England winter, the cold front was about to combine with the warm front in one of the worst storms ever to hit the Cape.”[3] “According to eyewitness accounts, gusts topped 70 miles [113 kilometers] an hour and the seas rose to 30 feet. [9 meters].”[4]

Square-rigged ships like the Whydah Galley did not handle so well in high winds, and since the winds were coming from the northeast, it was now pretty much out of the question for Bellamy to even try to attempt to head back out to sea. With each swell, the ship would have been pushed west by the winds, no matter how hard the pirates tried to keep heading north. One or more of them would have heard the sound of the waves hitting the shore and shouted, “Breakers, breakers!” But it was simply too late.

The accident was succinctly described by Thomas Davis in his deposition before his trial for piracy in Boston, Massachusetts, in October of 1717:

The Ship being at an Anchor, they cut their Cables and ran a shoar, in a quarter of an hour after the Ship struck, the Main-mast was carried by the board, and in the Morning She was beat to pieces. About Sixteen Prisoners drown’d, Crumpstey Master of the Pink being one, and One hundred and forty-four in all.[5]

“Although the beach was just 500 feet away, the bitter ocean temperatures were cold enough to kill the strongest swimmer within minutes. Other crew members were crushed by the weight of falling rigging, cannon, and cargo as the ship, her treasure, and the remaining men on board plunged to the ocean floor, swallowed up by the shifting sands of the cape.”[6] Anyone reaching the shore would then be faced with the challenge of climbing the seventy-foot cliffs (now called Marconi Beach).

Aftermath

When local residents arrived on the beach the next morning, “more than a hundred mutilated corpses lay at the wrack line with the ship’s timbers.”[7] Since the locals had no way of knowing how many men were on board the ship and obviously no knowledge of their names, individual corpses were not identified.

What Happened to the Others?

Around noon that same day nine men were arrested on suspicion of piracy. They had washed ashore off Wellfleet and were taken into the home of a local resident, where one of the original crew members of the Mary Anne, Andrew Mackonacky, exposed them as members of Bellamy’s crew.

First taken to Barnstable gaol in Wellfleet and then to Boston gaol the next day by horseback, Hendrick Quintor, Thomas South, Peter Cornelius Hoof, John Shuan, Thomas Baker, John Brown, Simon Van Vorst and Thomas Davis were tried in Boston, Massachusetts on 18 October 1717. South was the only one the court believed was a forced man and was acquitted. John Julian, also arrested that day, was sold into slavery. Davis was tried separately and also found not guilty.

Strange Tales Begin

Cape Cod folklore has many stories about a man who began to be seen not long after the wreck. The most famous reference to him is made by Henry David Thoreau, who wrote about the wreck of the Whydah and this stranger:

In the year 1717, a noted pirate named Bellamy was led on to the bar at Wellfleet by the captain of a snow which he had taken, to whom he had offered his vessel again if he would pilot him into Provincetown Harbor. Tradition says that the latter threw over a burning tar-barrel in the night, which drifted ashore; and the pirates followed it. A storm coming on, their whole fleet was wrecked, and more than hundred dead bodies lay along the shore. Six who escaped shipwreck were executed.

“At times to this day,” (1793) says the historian of Wellfleet, “there are King William and Queen Mary’s coppers picked up, and pieces of silver called cob-money. The violence of the seas moves the sands on the outer bar, so that at times the iron caboose of the ship [that is, Bellamy’s] at low ebbs has been seen.”

Another tells us that, “For many years after this shipwreck, a man of a very singular and frightful aspect used every spring and autumn to be seen traveling on the Cape, who was supposed to have been one of Bellamy’s crew. The presumption is that he went to some place where money had been secreted by the pirates, to get such a supply as his exigencies required. When he died, many pieces of gold were found in a girdle which he constantly wore.”[8]

Before the days of filing birth certificates with the county clerk and the Internet, it was not difficult for someone who wanted to escape the authorities to head a few towns away in any direction, make up a name, and start a new life.

The tales say that at night passers-by could hear screams and wails of torment and shouts of entreaty from within this man’s cabin. It as imagined that he was haunted by demons or the ghosts of his past crimes he had committed while pursuing a life of piracy.

Older tales told about how he frequently spent evenings in private houses, taking advantage of their hospitality to get free meals. If they had trouble getting him to leave, they simply started reading from the Bible or holding family devotions, causing him to leave.

Then, suddenly, they stopped seeing him. Some presumed he had traveled into Boston or another port and found work on a ship. Finally, someone was brave enough to enter his cabin, where he was found dead. Around his waist was a girdle filled with gold coins. He had claw marks around his neck.

A Last Tale

Amongst the many tales of this stranger is this one, which happened many years after the wreck:

One October [evening] in the year 1782, a resident of Eastham, after a great storm, decided to hike down along the beach toward the lower Cape, and reached the scene where the Whidaw had been wrecked… Far in the distance he saw a bonfire, and hastened toward it. Upon drawing closer, he discovered the same mysterious character known to almost every resident of that section.

This sinister individual, with a cocked pistol at his side, was three feet down, in a hole in the sand, and had just struck the top of a chest. The Eastham resident, in his excitement, dislodged a bit of material from the top of the cliff where he was walking, and the pirate, with an oath, sprang for his pistol.

The Cape Cod resident ran for the underbrush and escaped, but not before a close call from one of the pirate’s bullets. He returned several days later by daytime, but never found anything. The pirate was later found dead by the roadside with gold doubloons in his money belt.[9]

This last story is quite improbable, but the idea that someone could have survived the wreck is not impossible. Record-keeping in the early 1700s was rudimentary at best. And nearly all folklore has its basis in reality.

Let us know what you think of the article below.

Laura Nelson is the author of The Whydah Pirates Speak, available here: Amazon US | Amazon UK.

[1] Clifford, Barry, Real Pirates, p. 130.

[2] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited for Piracy,” p. 319. Peter Cornelius Hoof said in his testimony: “The Money taken in the Whido, which was reported to amount to 20000 to 30000 Pounds, was counted over in the Cabin, and put up in bags, Fifty Pounds to every Man’s share, there being 180 Men on Board… but none was to take any without the Quarter Masters leave.”

[3] Clifford, Barry, Expedition Whydah, p. 260. “Technically known as an occluded front, the warm and moist tropical air is driven for miles upward where it cools and falls at a very high speed, producing high winds, heavy rain, and severe lightning.”

[4] Donovan, Webster. “Pirates of the Whydah.”

[5] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited for Piracy,” p. 318.

[6] Clifford, Barry, Real Pirates, p. 131.

[7] Donovan, Webster. “Pirates of the Whydah.”

[8] Thoreau, Henry David. Cape Cod. p. 186-187.

[9] Snow, Edward Rowe. Boston Sunday Post (28 September

1947).