The naval victory at Midway on June 4, 1942 has rightly been recognized as one of the greatest in the history of the US Navy, and one of the most significant victories in the history of armed conflict. However, events did not follow the plan formulated by US Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester Nimitz, and the battle was very nearly lost by Pacific Fleet forces. Conspicuously missing from earlier accounts of the Battle of Midway is a description of the Nimitz plan to confront the Japanese carrier fleet.

Dale Jenkins explains. Dale is author of Diplomats & Admirals: From Failed Negotiations and Tragic Misjudgments to Powerful Leaders and Heroic Deeds, the Untold Story of the Pacific War from Pearl Harbor to Midway. Available here: Amazon US | Amazon UK

Chester Nimitz while Chief of Naval Operations.

The actions taken by Pacific Fleet forces during the Midway battle deviated significantly from the Nimitz plan. But, despite the deviation, the battle was won. What occurred at Midway was essentially a broken play, but positive action from a junior task force commander, astute calculations from an air group commander, and intrepid, skilled flying from carrier pilots saved the day.

The intelligence team at Pearl Harbor had decrypted sufficient Japanese messages by May 27 to advise Nimitz of expected Japanese fleet movements on June 4. Nimitz’s intelligence staff, headed by LCdr Edwin Layton, informed him that the Japanese carrier fleet, or Striking Force:

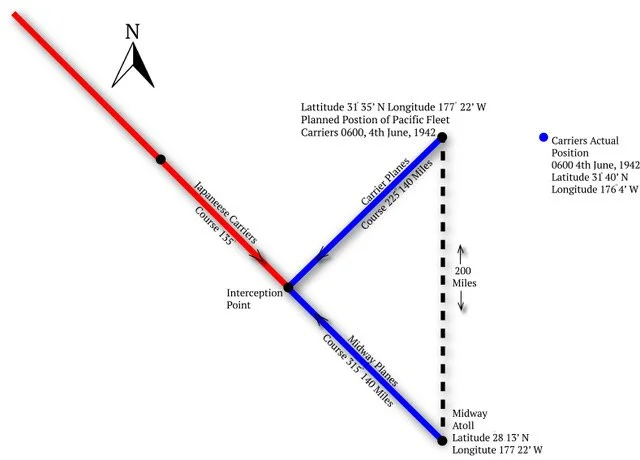

“would probably attack on the morning of 4 June, from the northwest on a bearing of 325 degrees. They could be sighted at about 175 miles from Midway at around 0700 (0600 local) time.”(1)

Layton expected four or five Japanese carriers steaming from the northwest at 26 knots. There were four: Akagi(flagship of carrier Striking Force commander Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo), Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu. Nimitz had a week to plan a defense of the attack, formulate a counter-attack, and continue to assemble forces on Midway to carry out the plan. He issued Operation Order 29-42 that detailed the forces that were to be employed, including the scouting operation of PBY amphibious planes and a picket line of submarines.

Additional Japanese forces included an amphibious Occupation Force operating south of the carrier force, a separate force to attack the Aleutian Islands, and a battleship force trailing 300 miles astern of the carriers. The battleship force included super-battleship Yamato with Combined Fleet commander Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto embarked.

The Japanese planned to launch 108 planes, half the total air complement of the four carriers, against the shore defenses of Midway Island at 0430 on June 4 when approximately 220-240 miles from Midway,. The remaining reserve force would be armed with anti-ship bombs and torpedoes to combat any unexpected Pacific Fleet forces. The Japanese command expected the Pacific Fleet carriers to rush to the scene from Pearl Harbor, and the Japanese would destroy them with their carrier planes and battleships in a showdown confrontation.

To counter the Japanese carrier force, Nimitz had planes on Midway Island and three Pacific Fleet carriers, Enterprise, Hornet and Yorktown, under the overall command of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. Fletcher, embarked on Yorktown, was in direct command of Task Force 17. A more junior rear admiral, Raymond Spruance, embarked on Enterprise, commanded Task Force 16 of Enterprise and Hornet.

Operating range

A particular problem was the difference in operating ranges between the Japanese carrier planes and those of the Pacific Fleet. The Japanese operating range was 240 miles, and the equivalent for the Pacific Fleet planes was just 175 miles. That difference meant the Japanese planes could attack the Pacific Fleet carriers when the Pacific Fleet planes were out of range of the Japanese carriers. Nimitz had to have a plan that would get the carriers through the band between 240 miles and 175 miles without being spotted and attacked. The difference, 65 miles, meant that a carrier covering that distance, averaging 25 knots, would have to steam for 2 ½ hours to cross the band where they were vulnerable to attack without being able to return it.

Nimitz designed an attack on the Japanese carrier fleet by moving the Pacific Fleet carriers through the night of June 3-4, under cover of darkness, to arrive at a position where they had the best chance to launch an attack before they were discovered by Japanese scouts. He planned to use PBY amphibious planes from Midway as scouts because the Japanese could sight the PBYs without being alerted to the presence of carriers. The light wind coming out of the southeast meant that the Japanese carriers, steaming into the wind, would launch and recover planes without changing course. Layton based his calculations on the PBYs taking off from Midway at 0430, plus plane and ship speeds, to arrive at his calculation that the PBYs should encounter the Japanese at about 0600, 175 miles from Midway. The planes on Midway would launch immediately upon receipt of the scouting report. Japanese carriers would move about 35 miles after the PBY report until the Midway planes intercepted them about 0720, 140 miles from Midway.

Nimitz formulated a plan for a concentration of force of Midway planes and carrier planes. To accomplish this, he determined that the Pacific Fleet carriers were to be at a position 140 miles northeast of the interception point at 0600. That position also was 200 miles directly north of Midway Island and was designated as the navigation reference point for the carrier force. When the report from a PBY was received at approximately 0600 the planes from both Midway and the three carriers would launch their planes. In a successful execution, all the Pacific Fleet planes would arrive over the Japanese carriers at approximately 0720 in a concentration of force. The goal was a victory by 0800-0815.

Because the Japanese planes attacking Midway would not return before 0830, the Pacific Fleet attack would be against just half of the Japanese air defenses. In addition, if the flight decks of the Japanese carriers were heavily damaged, even if the carriers themselves were not sunk, the planes returning from Midway would have to ditch in the ocean.

A graphic of Nimitz’s plan at the Battle. Copyright Dale Jenkins. Printed with permission.

After-action report

The after-action report of Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher confirms the intended movements of the carrier force in conformity with the Nimitz plan:

ENTERPRISE and HORNET maintained their air groups

In readiness as a striking force. During the night of June 3-4

both forces [TF-17 and TF-16] proceeded for a point two

hundred miles North of Midway. (Emphasis added) Reports of enemy forces to the Westward of Midway were received from Midway and Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet. These reports indicated the location of the enemy Occupation Force but not the Striking Force.(2)

The ComCruPac (Fletcher) report refers to PBY scouts on June 3, when the Occupation Force was sighted and the carrier Striking Force was still under heavy clouds. It confirms Fletcher’s knowledge of the plan and his intended movements. Further confirmation of the Nimitz plan and the ordered position of the carriers to be 200 miles north of Midway at 0600 on June 4 is contained in published accounts of at least three contemporary historians who had the opportunity to interview participants during and after the war: Richard W. Bates, Samuel Eliot Morison, and E. B. Potter. (3)

On June 3 the PBYs took off from Midway at 0430 and contacted the Japanese occupation force. This contact confirmed that the Japanese were proceeding with the plan as previously decrypted by Layton’s intelligence unit. The carrier force was still under a heavy weather overcast and was not discovered on June 3.

On June 4 the PBYs launched again at 0430. At 0534 a sighting of enemy carriers was transmitted to Admirals Fletcher and Spruance, and to the forces on Midway. At 0603 the earlier report was amplified:

“2 carriers and battleships bearing 320 degrees, distance 180, course 135, speed 25 knots.” (4)

Immediately after receiving the latter report the planes on Midway took to the air. Fighters rose to defend Midway, and six Avenger torpedo planes and four B-26s fitted with torpedoes flew to attack the Japanese carriers. Two more carriers were in the Japanese formation but were not seen by the PBY pilot.

However, Pacific Fleet carriers were not in position to launch planes at 0603 because Fletcher, while heading southwest overnight June 3-4 toward the designated position 200 miles north of Midway, decided that the scouting as ordered in Operation Order 29-42 might not be sufficient. At first light, he ordered Yorktown carrier planes to conduct a separate sweep to the north and east. To do this the carriers had to change course to the southeast to launch planes into the wind, and to be on that course to recover the planes. These course changes took the carriers away from the interception point. When the 0603 message from the scout arrived, the carriers were 200 miles east and north of the interception point and 25 miles beyond their operating range of 175 miles.

At 0607 Fletcher sent a message to Spruance:

“Proceed southwesterly and attack enemy carriers when definitely located. I will follow as soon as planes recovered.”(5)

Spruance, detached with Enterprise and Hornet, proceeded southwest at all possible speed to close the range, but at an average speed of 25 knots it would take an hour to cover 25 miles. Meanwhile, the planes from Midway arrived separately over the Japanese carriers and attacked. The plan for a concentration of force had failed.

The Avengers and B-26s, arriving at 0710, flew into the teeth of the Zero fighter defenders. They attempted valiant torpedo runs against two of the four carriers, but the inexperienced pilots were hopelessly outclassed by the fast, agile and deadly Zeros. There were no hits or even good chances for hits, and the Zeros sent five of the six Avengers flaming into the ocean. The B-26s hardly did better, but one pilot, with his plane on fire and probably knowing he was never getting home, dove at the bridge of the Japanese flagship. He missed by a few feet and crashed into the ocean.

B-26 pilot

The B-26 pilot may have done as much as anyone that day to turn the tide of the battle. At 0715 the shocked Admiral Nagumo, already notified that the Midway attack had run into heavy resistance, decided that a second attack on Midway was required. He ordered the armaments of the standby force to be changed from anti-ship bombs and torpedoes to point detonating bombs for land targets. All of this would require over an hour to complete, and not before the Midway attack force would be returning to land about 0830, low on fuel.

Admiral Spruance, ready to launch planes from his two carriers at 0700, plotted courses to a new interception. Ranging closely together between 231 degrees and 240 degrees, but delayed at the launch, the planes expected to arrive at the new interception at 0925 – almost 2 1/2 hours after the launch time.

At 0917, with the Midway force landed, Admiral Nagumo turned northeast to confront the Pacific Fleet carriers that a Japanese scout had discovered earlier. Decisions he had made, including landing the Midway planes, had delayed any attack on the American carriers. The Americans were still making attacks, but the Zeros swept them aside easily. Now Nagumo was supremely confident. Rearming and refueling the entire air complement on all four carriers would be completed by 1045. They would launch a massive, coordinated attack of over 200 planes and sink the American carrier fleet.

The Enterprise and Hornet planes crossed the revised intercept point at 0925 but found nothing but open ocean. The Hornet air group commander took his squadrons southeast to protect Midway. The Enterprise air commander realized that the Japanese carrier force probably had been delayed by earlier actions. He took two squadrons of dive bombers on a northwest course to retrace the Japanese movements, then began a box search that came upon a Japanese destroyer, and that led to the Japanese carriers. Diving out of the sun at 1025 caught the Japanese defenders by surprise, and in five minutes Akagi and Kaga were destroyed. The Yorktown planes suddenly appeared and destroyed Soryu.

Hiryu, the remaining Japanese carrier, launched dive bomber and torpedo plane attacks which led to the loss of Yorktown. Later in the day on June 4 Enterprise dive bombers destroyed Hiryu. The greatest victory of the US Navy had been realized.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the Midway victory no one was going to complain about not following the Nimitz battle plan, least of all Admiral Nimitz. Consequently, the existence of the plan has been overlooked until now. Whether following the plan would have resulted in the same victory by Pacific Fleet forces, or the same victory without as many losses in ships, planes and personnel, has never been explored and is left to speculation.

As a reminder, Dale is author of Diplomats & Admirals: From Failed Negotiations and Tragic Misjudgments to Powerful Leaders and Heroic Deeds, the Untold Story of the Pacific War from Pearl Harbor to Midway. Available here: Amazon US | Amazon UK

References

(1) Layton, Edwin T., And I Was There, Konecky & Konecky, Old Saybrook, CT, 1985, p. 430

(2) Report of Commander Cruisers, Pacific Fleet (Adm. Fletcher), To: Commander-in-Chief,

United States Pacific Fleet, Subject: Battle of Midway, 14 June 1942, Pearl Harbor, T.H., Para. 3, included as Enclosure (H) in United States Pacific Fleet, Advance Report – Battle of Midway, 15 June 1942

(3) Bates, Richard W., The Battle of Midway, U.S. Naval War College, 1948, p. 108; Morison, Samuel Eliot, Coral Sea, Midway, and Submarine Actions, Naval Institute Press, 1949, p. 102; Potter, E.B., Nimitz, Naval Institute Press, 1976, p. 87.

(4) Morison, p. 103.

(5) Morison, p.113