Success at learning

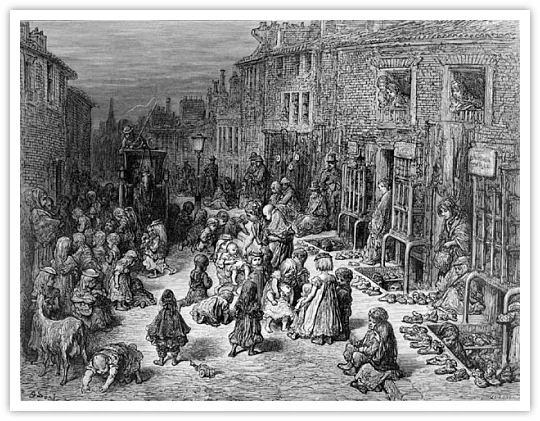

The youngest boy of seven children, Braun was born in June of 1850 at Fulda, a town northeast of Frankfurt still enclosed in its medieval walls. Despite his father's job as a mid level civil servant, Braun was raised in extreme poverty due to the billeting of Bavarian soldiers in his home. A time of unrest in Germany, Fulda was forced to house many soldiers forcing its inhabitants into sheds and barns, while the poor ate rodents to survive. Despite these inauspicious beginnings, Braun did attend to school. Hardly a prodigy, the fact that he had difficulty with mathematics outside of theory was often laughed at later in his life. Despite this, Braun wrote a book on crystallography when he was 15. Reviewed favorably by several professors it went unpublished due to his age. However Braun was undeterred, publishing several papers on aspects of chemistry before he turned 17.

Braun enrolled in experimental physics, mathematics, and chemistry at the college in Marburg just before his 18th year. Due to his physics professor's musical inclinations his studies were focused on acoustics, which while good at, Braun was not inclined to pursue. Even so, it is likely that his understanding of the concept of resonance would later play a role in his inspired electrical innovations. Dissatisfied with the scope of his studies at Marburg - with its mere 355 students and unimaginative professors - Braun cleared financial hurdles and went on to the University of Berlin, an undisputed leader in science, after his second semester at Marburg.

In Berlin, an elite physics laboratory existed with only 3 of 265 science students allowed access. Braun, after a single interview with the professor in charge, was allowed use of the lab in complete privacy and at no expense, an honor almost unheard of. Morally and financially compelled to return to Marburg after two semesters to please his father, Braun's next break came when offered a paid internship as a laboratory assistant and lecturer at what was to later become a section of the Technical University of Berlin. This allowed him to stay in Berlin under the tutelage of a Professor Quincke who promoted the spirit of German scientific education, something that was to eventually propagate through much of the academic world. This pairing reaped great benefits for mankind.

Braun's first dissertation earned him the beginnings of a reputation. His acumen for the mechanics of experimentation became evident to all those involved. His contributions to scientific knowledge are too numerous to even outline here, but his discovery of the "diode" effect should be mentioned. This discovery effectively makes him the great grandfather of every semiconductor ever manufactured. Braun was the teacher that every student hopes to get and if they do, they remember him for life. Braun taught at numerous German universities and his talent for amusing anecdotes once had Kaiser Wilhelm II repeatedly slap his leg and laugh during a lecture.

A history of invention

In the latter half of the 19th century, electricity was working its way into industry and society. Batteries, generators, lights, telegraphs, and other assorted technologies were being implemented while barely being understood. Braun was asked by early German electricity producers for help with various aspects of energy propagation. With characteristic energy, he tackled the problem by refining ideas published by Roentgen, the discoverer of X-Rays. Braun's solution to probing the inner workings of electrical circuits was the creation of the Cathode Ray Tube. A long glass tube with the air pumped out and two metal plates with a phosphor coated "screen" of cardboard. Braun was the first to control the horizontal and the vertical by waving magnets around the tube to deflect the electron beam, or cathode ray, which was a discovery in itself.

Braun, a kindred soul to Tesla and never a businessman by nature, altruistically published his findings with expediency, despite being aware of the enormous fiscal value of his invention. He honed his marvelous tube into what is known today as an oscilloscope, a fundamentally unchanged tool of electronics that is indispensable to any electronic engineer or technician. It was Braun's oscilloscope that first showed the German electricity producers that the electricity they were creating operated at a frequency of 50 "hertz" or cycles per second - a frequency unchanged in Europe to this day. To say the German industrialists involved were pleased with Braun's "Scope" is a huge understatement. Braun contributed many other items to the electric industry and his brother, a successful merchant, founded a company to reap some gain from Braun's inventive mind. The most pervasive legacy of this company remains with us in the form of the Braun electric razor. His tube, known in America as the CRT, is still called "Braunsche Rohre" (Braun's Tube) in German speaking countries and "Buraun-kan" in Japan.

At the tail end of the 19th century "wireless" communication was in its infancy, and utilizing "Spark Gap Transmitters" and releasing barely manipulated EMP (electro-magnetic pulse) assaults into the atmosphere, Braun hoped that someone could pick them up at distances measured in single to double digit miles. If one of these transmitters were "sparked up" today in a modern city, it is likely that all the iPads, iPods, and cell phones in the immediate area would suffer a premature death, all their semiconductor junctions fried at the hands of raw electromagnetic energy.

World War I and change

Ferdinand Braun helped change all that. Braun and Marconi were jointly awarded a Nobel Prize in 1909 for "contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy." Marconi even admitted to Braun himself that he "borrowed" several of Braun's patents. It was during his work on wireless telegraphy that Braun invented the first diode, without which there would be no modern electronics as we know it. It was also here that Braun's early work with acoustic resonance came into play as he improved the wireless technology including inventing the phased array antenna.

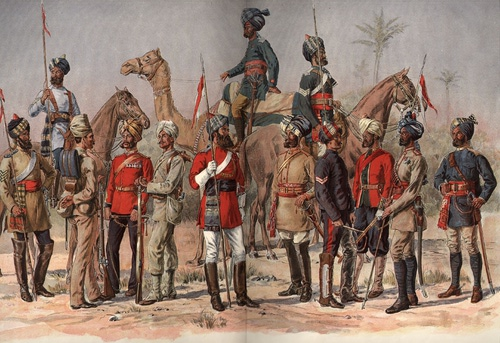

During the Russo-Japanese war of the early 20th century and before the outbreak of WWI, the combat efficacy of wireless communications was proven by the Japanese sinking of the Russian flagship Petropavlovsk. Baited out of Port Arthur with small ships, torpedo boats were called in as reinforcements by wireless. At the outbreak of WWI, Braun's workplace, then at Strasbourg, was shut down and the city filled with troops. Braun's family was scattered by various circumstances. When the tide of war ebbed Braun returned to Strasbourg to find his university's station locked behind closed doors, being used by the military as one point of the first known radio triangulation efforts to track ships at sea. The British ships were tracked and the U-boats success at finding prey may have been due to this effort.

Prior to the war, with Marconi's efforts tied up, the only world wide network of communications was set up by Telefunken. Many pieces of this network were destroyed in the early days of the war in an effort to isolate Germany. The Sayville station, outside New York and the last of the offshore Telefunken stations to remain operational, had recently been upgraded and was able to receive reports from Germany. It came under assault for patent infringements in efforts to shut it down, with Marconi himself scheduled to testify. Braun decided to travel to New York to help counter the British efforts to shut it down. Diagnosed and treated for cancer ten years earlier though, the disease was rearing its head again making Braun aware that this trip might be the last effort of his life. Risking winter travel and the Atlantic blockade (his own son had been caught at sea returning from America and imprisoned), Braun left for New York without much hope of seeing his homeland or family again. Departing from Bergen, the captain went far out of the normal sea routes, passing just south of Iceland to deliver his "cargo," for, besides Braun and his three companions, the ship was carrying a new transmitter and antenna setup for the Sayville station. Shortly after Braun's arrival in New York he had a pleasant surprise when his son, released from internment by the British, was allowed to return to America.

In part due to Braun's presence, the lawsuit against Sayville went in Telefunken's subsidiary's favor. However Sayville was taken over by the US Navy when America declared war on Germany.

His job done, Braun petitioned the British government for safe passage to Germany but they were non-committal. Braun remained in America under the watchful eyes of British intelligence, and coming to the realization that the British did not want him back in Germany, Braun resigned himself to life in the Catskill Mountains of New York until the war ended. Many American scientific groups, pleased to have a Nobel Prize winner nearby, treated him to feasts and event invitations, easing his isolation. He continued to write articles on physics, one of his last being "Physics for Women," a practical aid to housewives everywhere. In 1918 Braun slipped and fell. He broke his hip, went into a sickbed, and never arose. He passed away shortly thereafter.

Scientist, teacher, innovator, and patriot to his country, Braun was a remarkable and admirable man written out of history by the winners of WWI. The next time you view the iconic 1960s TV show The Outer Limits’ introduction, with its elemental display of oscilloscope functionality, take a moment to reflect upon a 20th century without the Cathode Ray Tube. Braun was the first to control the horizontal and vertical, bringing much of physics in to crystal clarity. Life would not be the same without his wonderful "Braunsche Rohre" and other miraculous inventions.

This article is by Kevin K. O’Neill.

You can read another article by Kevin, related to ghosts and science in the 19th century, here.