In William Bodkin’s fifth post on the presidents of the USA, he reveals a fascinating tale on the Forgotten Founder, James Monroe (in office from 1817 to 1825). And the real reason why he was not unanimously re-elected to the presidency.

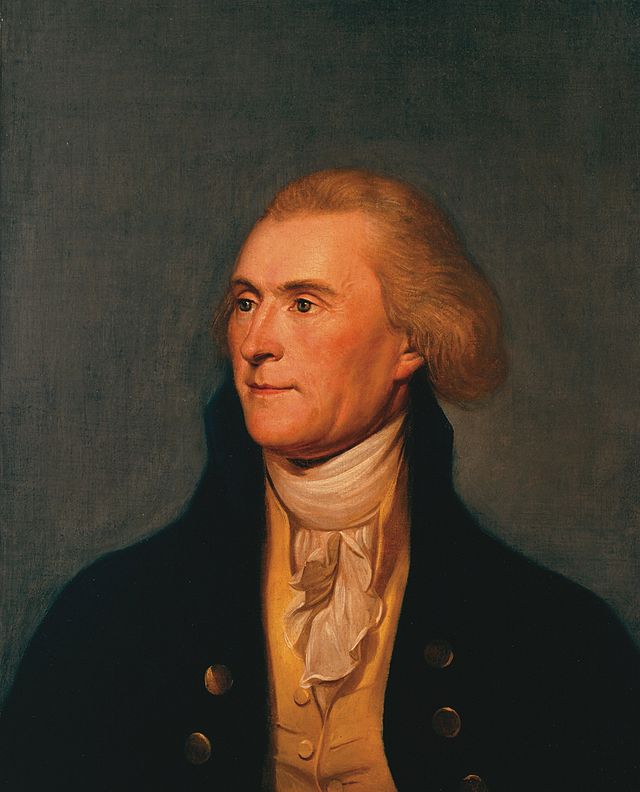

William's previous pieces have been on George Washington (link here), John Adams (link here), Thomas Jefferson (link here), and James Madison (link here).

James Monroe as painted by William James Hubbard in the 1830s.

James Monroe, fifth President of the United States, was the last American Founder to become President and a hero of the Revolutionary War. At the Battle of Trenton, Monroe, then a Lieutenant, and Captain William Washington, a cousin of George Washington, stormed a Hessian gun battery to prevent what would have been the certain slaughter of advancing American troops. Captain Washington, Lieutenant Monroe and their men seized the Hessians’ guns as they attempted to reload. For their efforts, Captain Washington’s hands were badly wounded, and Monroe was struck in the shoulder by a musket ball, which severed an artery. Monroe’s life was saved by a local patriot doctor who clamped the artery to stop the bleeding.[1] Monroe’s heroism was such that it is said that in the famous painting Washington Crossing the Delaware, capturing the moment when George Washington led the Continental Army into New Jersey prior to the Battle of Trenton, James Monroe stands next to George Washington, holding the American flag.[2]

Following the revolution, Monroe embarked on a long career in service of the new nation. He studied law with Thomas Jefferson, and then served as a United States Senator from Virginia, Ambassador to France, Governor of Virginia, Ambassador to England, Secretary of State and Secretary of War during James Madison’s administration, and was then twice elected President.

Despite this heroic and distinguished career, Monroe seems overlooked as a Founder, eclipsed by the long shadows of Washington, Adams, Jefferson and Madison, his presidential predecessors who created the new nation with their considerable intellects and political skills. Perhaps this is because Monroe was not considered their equal. William Plumer, a US Senator from New Hampshire, who went on to serve as Governor of that state, described Monroe as “honest”, but “a man of plain common sense, practical, but not scientific.”[3]

James Monroe is generally remembered for two things: the Monroe Doctrine, which sought to block Europe from further colonizing the Americas; and the fact that he was almost unanimously elected to his second term. History tells us that Monroe was denied a unanimous second term for the noblest of reasons. One defiant elector in the Electoral College voted for John Quincy Adams because he believed that George Washington should be the only unanimously elected President of the United States.[4]

Except that is not true, and the real reason is a lot more interesting. The truth involves William Plumer, who did not think much of Monroe, Daniel Tompkins, a Vice-President frequently too drunk to preside over the Senate, and the greatest orator in American history, Daniel Webster.

Unpacking the real story

Following the War of 1812, post American Revolution political tensions eased into the “Era of Good Feelings.” The Federalist Party had collapsed following the revelation that during the war, they were plotting to secede from the union,[5] essentially leaving no other national party to challenge the Democratic-Republicans of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe. The country, though, was not united behind Monroe, he just had no organized opposition. Monroe faced plenty of criticism, including from Thomas Jefferson, who opposed his former law student’s extravagant deficit spending and expansion of the federal government.[6] But with the Federalist Party unable to put up a national candidate for president, there was no way to protest Monroe’s policies. At least, not until a plan was hatched by Daniel Webster to protest Monroe by voting against the re-election of Daniel Tompkins to the Vice-Presidency.

Tompkins was widely regarded as a failed Vice-President. A former Governor of New York, Tompkins was far more interested in his state, even running again for Governor in 1820, just prior to being re-elected Vice-President. Tompkins was also a chronic alcoholic.[7] His alcoholism, though, was allegedly tied to a valiant cause. As New York’s Governor, Tompkins personally financed the participation of the state’s militias in the War of 1812 when the New York State Legislature voted against providing the funding. After the war, however, the state refused to reimburse him, causing him financial ruin.[8]

Despite the noble roots of Tompkins’ problems, Webster resolved to vote against him. Webster settled on a plan to gather votes for John Quincy Adams, the son of John Adams and then James Monroe’s Secretary of State. This plan was complicated, however, by the fact that Webster was a presidential elector from the state of Massachusetts. The head of that Electoral College delegation was John Adams. Webster, perhaps wisely, chose not to broach the subject with the former president. Instead, Webster sent an emissary to William Plumer, then mostly retired from political life, but who was serving as the head of New Hampshire’s Electoral College delegation, to enlist him in the plan.[9]

The vote against

Plumer embraced the idea. He sent a letter to his son, William Plumer, Jr., New Hampshire’s Congressman, asking him to approach John Quincy Adams with the idea. When the younger Plumer did, however, Adams was appalled. Adams noted that any vote for him, in any capacity, would be “peculiarly embarrassing”, especially if it came from Massachusetts. Adams made clear to Plumer he wished Monroe and Tompkins be re-elected unanimously, and that, in any event, there should not be a single vote given to him. Adams told Plumer that a vote for him would damage his prospects for winning the presidency in 1824.[10]

Plumer sent word to his father immediately, but it did not reach the elder Plumer before he left for Concord, New Hampshire, to cast his electoral vote. It is not clear where Plumer resolved to vote for John Quincy Adams not for Vice-President, but for President, and to do so as a protest against Monroe himself.[11] But he did. In a speech to his fellow electors, the elder Plumer announced his intention to vote for John Quincy Adams for president. In his remarks, Plumer stated that Monroe had conducted himself improperly as president, echoing Jefferson’s complaints concerning the vast increase of the public debt during the Monroe administration.[12]

How does George Washington fit into this? It is really not known. Newspaper accounts of the time accurately recorded Plumer’s dissent.[13] The first references to Plumer’s vote preserving Washington’s status emerged in the 1870s, when historians assessing the Founding Era noted the parallels between its beginnings, with the unanimous acclamation of George Washington as the indispensable man to the Republic, and its end, with its unanimous acceptance of James Monroe as the man no one opposed. The theory was first floated around then and it took on a life of its own.[14] In the absence of clear evidence of how this American legend began, perhaps it was just one of history’s quirks that James Monroe, who nearly sacrificed his life in service to George Washington’s army, was destined to sacrifice part of his historic reputation in service of creating the myth of George Washington, Father of the United States.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

[1] For the full story, see David Hackett Fisher’s “Washington’s Crossing” (Pivotal Moments in American History), Oxford University Press (2004).

[2] http://www.ushistory.org/washingtoncrossing/history/whatswrong.html

[3] William Plumer, Memorandum of Proceedings in the United State Senate, March 16, 1806.

[4] See, Boller, Paul F., Jr. Presidential Campaigns from George Washington to George W. Bush, Oxford University Press (2004), p. 31-32.

[5] See, connecticuthistory.org/the-hartford-convention-today-in-history/

[6] Letter of Thomas Jefferson to Albert Gallatin, December 26, 1820.

[7] Letter of William Plumer, Jr. to William Plumer, his father, on February 1, 1822, describing Tompkins as

“so grossly intemperate as to be totally unfit for business.”

[8] http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Daniel_Tompkins.htm

[9] Turner, Lynn W. “The Electoral Vote Against Monroe in 1820—An American Legend” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 42(2), (1955), pp. 250-273

[10] Turner, p. 257

[11] Turner, p. 258

[12] Turner, p. 259

[13] Turner, p. 261.

[14] Turner p. 269-270.