Andrew Jackson was in many ways the first ‘self-made’ president of the USA. Not a member of any of the traditional ‘elites’, Jackson fought his way up to the top. And after being robbed of victory in the 1824 presidential election, he created an innovative way to win in 1828. William Bodkin explains.

A colored image of Andre Jackson, US President 1829-1837.

Andrew Jackson was different from the presidents who preceded him. Neither a Founding Father nor a Founding Son, he was not a prosperous Virginia landowner and was not a member of one of Massachusetts’ preeminent families. Perhaps as a result, after having had the presidency essentially stolen from him in 1824 despite winning the popular vote, Jackson and his supporters felt he needed something extra to put him over the top.

In 1828, something happened that provided the template for nearly every later presidential campaign.

Becoming Old Hickory

But what made Jackson a presidential contender? Jackson was, in many ways, the first presidential candidate from the “up-by-your-bootstraps” American tradition. Born in the backwoods of North Carolina in 1767, Jackson first distinguished himself as a teenage soldier in the Revolutionary War fighting with an American irregular unit. But the war was cruel to Jackson’s family. One brother died in combat, and Jackson’s mother and other brother died of smallpox immediately after the war in 1781. Jackson, then aged fifteen, was a battle-hardened veteran, alone and adrift in the world.

The law provided solace and eventually the path to accomplishment. Jackson read law for two years in North Carolina, and then took the opportunity to become a public prosecutor in Nashville. His career took off in the then frontier town: lawyer, delegate to Tennessee’s Constitutional Convention, the State’s first Congressman, a Senator, and then a return home to be a Superior Court judge. It was while judge that Jackson, in 1802, challenged the state’s governor in an election to be major general of the Tennessee militia. Jackson won handily. Further military exploits would prove elusive, though, until the War of 1812.

During the winter of 1812-1813, the call came for the Tennessee state militia to defend New Orleans. Jackson mustered 2,000 men, and, in January 1813, marched them as far as Natchez, Mississippi. For reasons that were unclear at the time and remain so to this day, the Secretary of War ordered Jackson to disband his men and head back to Nashville. But neither provisions nor pay were provided for the march home. Jackson thundered that he and his men had been abandoned in a strange country, but he vowed that he would never leave his men and would make every sacrifice to ensure his army’s safe return to Nashville. Jackson ordered his officers off their horses, and he gave up his own horses so volunteers who were sick or injured could ride back. Jackson, on foot, led the march back to Nashville. By the end of the journey, his men were calling him “Old Hickory” in tribute to his steadfastness and courage. Heroism, and an all-out rout of the British at New Orleans, came later.

Pursuing the Presidency

How was the 1824 election stolen from Old Hickory? Jackson was one of four presidential candidates that year, alongside John Quincy Adams, who had most recently served as James Monroe’s Secretary of State, William Crawford, who had most recently served as Monroe’s Secretary of the Treasury, and Henry Clay, then Speaker of the House of Representatives. Jackson won the popular vote, but no candidate won a majority of the Electoral College vote, sending the election to the House of Representatives. Clay, who had led some of the campaign’s sharpest attacks on Jackson, simply could not stand to see the presidency go to a man he thoroughly despised. Instead, Clay cut a deal with the supporters of John Quincy Adams to give his support to him in exchange for being nominated Secretary of State. Adams agreed, and what would go down in history as the “Corrupt Bargain” was sealed.

Following this defeat, on his return to Nashville from Washington, Jackson was greeted at every stop by supporters who expressed their fury. There was a will to overturn the Corrupt Bargain; all that was needed was the way. Into this breach stepped the United States Senator from New York, Martin Van Buren. Van Buren was the head of the “Albany Regency”, which was the first political machine in the United States. Through a shrewd combination of strict enforcement of party loyalty and strategic rewards via patronage appointments, Van Buren had gained control of New York State, and was eventually sent to represent it in the Senate while his loyalists maintained their grip at home.

Van Buren, perhaps a pure political pragmatist, chose as his first task the co-opting of John Quincy Adams’ Vice President, South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun. Van Buren sought to bring about an alliance of the plantation owners of the South and the Republicans of the North to deny Adams a second term. Calhoun, who had become completely alienated by John Quincy Adams, agreed to run as Jackson’s Vice-President. However, even as Van Buren courted various political leaders on Jackson’s behalf, he did not lose sight of the opportunity to court the popular vote. In doing so, Van Buren drew a sharp contrast between his war hero candidate and the notoriously aloof Adams, who, concerning his reelection, had observed that if the nation wanted his continued services as president, it must ask for them. Van Buren and his associates hatched a plan that revolved around Jackson’s rough-hewn image, embodied by his “Old Hickory” nickname.

Selling Old Hickory

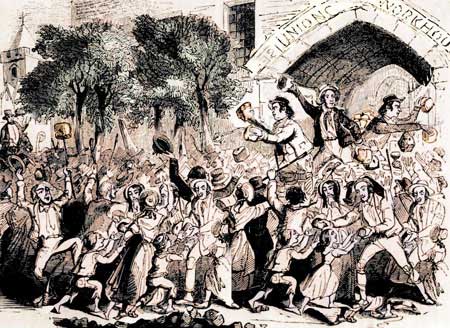

“Old Hickory” became the first brand name in presidential politics. Local political organizations supporting Jackson became “Hickory Clubs,” raising “Hickory poles” and planting hickory trees at barbecues and rallies. Drawings of hickory branches and leaves, along with likeness of Jackson adorned campaign paraphernalia, from badges to plates and pitchers, even snuffboxes and ladies’ combs. The Jackson campaign became a popular juggernaut the likes of which the new nation had never seen before, and that the Adams forces were powerless to stop.

Not that they didn’t try. Jackson was roundly pilloried for his marriage to his beloved wife, Rachel, whom he had the misfortune to meet while she was married to another man. They were smitten with each other nonetheless, and lived together as man and wife for years in the early 1800s before she received her divorce. The Jackson forces explained the oversight by stating that the couple thought Rachel had received her divorce, and quickly remedied it when they learned she had not. Jackson’s mother was not even spared the vitriol. One newspaper editor questioned Jackson’s parentage, printing that Old Hickory’s mother was a prostitute who had been brought to America by British soldiers, and who afterward married a mulatto with whom she had several children, Jackson being one.

These attacks, though, were of no avail. Jackson captured 56% of the popular vote and the Electoral College vote over Adams 178-83. The campaign masterminded by Van Buren expertly exploited the growth in importance of the popular vote in American politics, as the nation drifted away from the Founders and began to carve out a separate, more democratic, identity. Politics, in many ways, became a form of entertainment and sport for the people, with the “Old Hickory” collectibles and Jackson’s mass appeal forming a common bond among the common man, whether he lived in New York State, Tennessee, or Florida. So next time election season rolls around, and your neighborhood is once again awash in buntings, yard signs, pins, bumper stickers and coffee mugs promoting the candidates, give thanks to Andrew Jackson, and really Martin Van Buren. And remember that in America, campaign marketing and merchandise, in its own way, helped forge the many states into one Union.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

William's previous pieces have been on George Washington (link here), John Adams (link here), Thomas Jefferson (link here), James Madison (link here), James Monroe (link here), and John Quincy Adams (link here).

Sources

- Jules Witcover, Party of the People, a History of the Democrats, Chapter 7, “Jacksonian Democracy” (Random House, 2003).

- Jon Meacham, “American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House.” (Random House, 2008).

- Miller Center of the University of Virginia (www.millercenter.org); American President Andrew Jackson (http://millercenter.org/president/jackson).

- “The 1824 Election and the Corrupt Bargain” (http://www.ushistory.org/us/23d.asp).

- Public Relations Society of America, “Andrew Jackson—Founding Father of Politics As Usual” (http://www.prsa.org/SearchResults/view/7630/105/Bonus_online_article_Andrew_Jackson_founding_fathe#.VIUW5ofq2EQ).

- John C. Calhoun, 7th Vice President (http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_John_Calhoun.htm).