Napoleon Bonaparte was famously defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 by British and Prussian forces. But what if that never happened? How would European history have changed if Napoleon had won? Here, Nick Tingley explores why history may have ended up repeating itself…

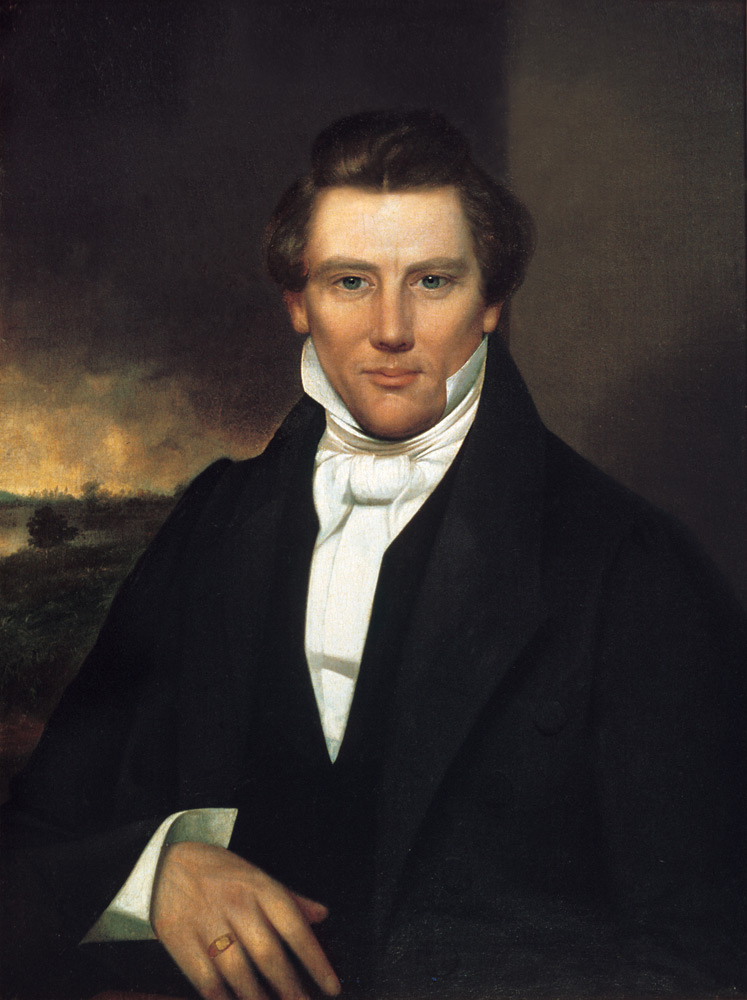

A picture of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The battle between France and Prussia in 1870 was all but decided at the Battle of Sedan on September 1. As Napoleon III was led through the French countryside for the nearest port, he knew that this battle would spell the end of the Empire. As he was sailed across to England for exile, a unified Germany was created off the back of French territory - and the landscape of Europe would be forever changed.

Had he been more like his uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte, the fall of Napoleon III’s government might never have happened. Bonaparte had known when to give up. Even as the British troops of Wellington and Blucher’s Prussians fled from the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Bonaparte had known that he had to pursue peace in order to survive. Bonaparte had even offered clemency to the British troops by aiding their evacuation from France after the battle, essentially bringing about a new era of peace in Europe championed by the two enemy nations. Bonaparte had developed so much since 1813 when he had refused a favorable settlement in defeat that he was able to bring about the longest lasting peace that Europe had seen in centuries…

But Napoleon III had not learnt from his uncle’s mistakes and the horrendous defeat at the Battle of Sedan would haunt him until his death in 1873…

When ‘What If’ Collides with History

Ironically, for a ‘What If?’ scenario, this version of history is not remarkably unlike our own. Whilst Napoleon Bonaparte did not win the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, his nephew did eventually become Emperor of France as a result of the 1848 revolutions that sprung up around Europe. His last act as Emperor was to lead French forces against Prussia in the War of 1870. He was captured at the Battle of Sedan and forced into exile in Britain, where he was forever haunted by the destruction of his Empire. His actions that year effectively allowed the creation of Germany that was, in no small part, responsible for much of the tension between the two countries over the next seventy-five years.

And yet, this event in history may well have occurred regardless of whether Bonaparte had won the Battle of Waterloo. If we suppose, for a moment, that Napoleon had managed to defeat the British and Prussian forces at the battle and maintain control of France thereafter, it is not beyond reason to suppose that, as Bonaparte’s nephew and heir, Napoleon III would have inherited the Empire anyway. Had that happened, the Battle of Sedan would almost certainly have occurred in the same way, leading to his downfall and the beginning of the tensions that would contribute to the outbreak of the First World War.

But what scenario would allow such a divergence from historical fact and yet still arrive at the same point fifty-five years later? Rather than looking to Napoleon III, our attention must be drawn to Bonaparte, the man whose decisions would ultimately determine the future of France and the rest of Europe.

Bonaparte the Warrior

At first we must address Bonaparte’s character. The Bonaparte of 1796, the year that he began his conquest of Europe, was a war leader to the greatest degree. Had he managed to defeat Wellington and Blucher at Waterloo, he would almost certainly have urged his officers to press after Wellington and Blucher’s scattered armies until every last one of them had been captured or killed. He would have then have turned his attention to the armies of Russia and Austria who, whilst not involved in Waterloo, were slowly advancing across Europe to address this resurgence of power.

This would have presented Bonaparte with a serious problem. In the first instance, Austria and Russia had armies of approximately 200,000 men working their way across Europe. In the second, Alexander I, the Tsar of Russia, was particularly keen to eliminate Bonaparte, as he believed that Europe would never remain at peace with him alive. Finally, French conscription, from which Bonaparte had been gathering troops during his previous campaigns, was not currently a policy in France. This meant that he didn’t have access to the same amount of reserves that he had previously.

In this scenario, Bonaparte would probably not have enjoyed any significant success for more than a week or two. With the arrival of the Austrians and Russians, Bonaparte’s armies would have stood little chance at all, and history would have certainly continued down the path that we are most familiar with.

Bonaparte the Stubborn

The Bonaparte of 1813 may have lasted even less time. In 1813, Bonaparte had refused any kind of settlement at all, even though he had been completely defeated at the Battle of Leipzig that year. In that battle, Bonaparte’s armies were effectively expelled from the rest of Europe and forced to retreat back in to France. Had Bonaparte sued for a peace at that time, he might well have retained his title and control over France. The result of his failure to do so was the invasion of France by the Coalition of Russia, Austria and Prussia and his own removal from the throne.

Had he treated his victory at Waterloo with the same refusal to negotiate, Bonaparte would have probably attempted to retake parts of Central Europe immediately following the Battle of Waterloo. Once again, Bonaparte’s failing would have been signaled by the arrival of Russian and Austrian troops which would have led to yet another disastrous retreat back in to France, if not the destruction of his entire army.

Bonaparte the Diplomat

There is, however, one scenario by which Bonaparte may have been able to win at Waterloo and still maintain control of France. If Bonaparte had granted clemency to the retreating British forces of Wellington, history could have taken a completely different turn. The British forces had granted something similar seven years previously at Sintra, where French forces had been allowed to evacuate from Portugal after several disastrous battles. Such an act of honor, whilst completely removed from Bonaparte’s character, may well have been enough to convince the British that there might be a peaceful solution to the French problem.

In the event that Bonaparte had sued for some sort of peace, before the arrival of the Russian and Austrian armies, they may well have found a new ally in the form of Britain. With the two former enemies working together to bring about a new era of peace, it is not beyond reason to suggest that the rest of Europe might have been tempted to follow suit. The Congress system that was prevalent in Europe for the years following Bonaparte’s downfall may well have still existed but with a stronger leader speaking on behalf of France.

However, all of this would rely heavily on Bonaparte being able to disregard all the previous behaviors that had come to define his reign. In order for this scenario to work, Bonaparte would have had to cease behaving like some sort of power-hungry megalomaniac and become a reasonable diplomatic presence in Europe. One can even imagine that, had Bonaparte become the diplomat that Europe needed him to be, the rise of Germany might have been significantly delayed.

The revolutions of 1848 might have been a significantly smaller affair as there would have been no antagonism towards a French monarchy, which would have disbanded with Bonaparte’s renewed rise to power, and therefore no revolution in France. The French revolution, which was one of the larger and more explosive of the 1848 revolutions, would not have existed to encourage the others across Europe. Without the discontent across Europe, we can easily see a scenario in which a united Germany never comes in to being, effectively removing the threat of World War One in 1914 and, therefore, the subsequent World War twenty-five years later.

The Likely Scenario

Unfortunately, Bonaparte’s actions were, by and large, a result of his psychological compulsions and the environment in which he came to power. He was very much a child of the French Revolution; his rise to power had been as a result of one of the bloodiest events in French history. The idea that a man, who owed so much of his power to man’s compulsion towards war, would be content at sitting around a conference table with the other leaders of Europe is improbable at best.

Had he been given the opportunity to make this decision, it is unlikely that he would have taken it, opting instead for the allure of battle. In the event that he had sued for peace, it would almost have certainly been a blind to allow himself time to build up his armies before making another attempt at conquering the continent. In all likelihood, rather than delaying the onset of a World War in Europe, he would almost have certainly caused one in his own right.

However, Bonaparte would not have had long to enact his plans. Barely six years after his victory at Waterloo, he would have succumbed to the pain of stomach cancer and his throne would have been left to his then thirteen-year old heir and nephew, Napoleon III. What chaos would have gripped France as a result of his death is almost unfathomable and not within the remit of this discussion. However, two scenarios present themselves. Either, under the influence of the rest of Europe, France would have returned to a monarchy-led government and once again would have continued down the course that we already know from history, or else the young Napoleon III would have taken to the throne, probably starting a civil war in the process. If Napoleon III were to survive such a period of unrest in France, he could have reigned for nearly fifty years, never having the opportunity to learn from his uncle that the best direction for Europe was towards peace…

Did you enjoy this article? If so, tell the world! Tweet about it, like it or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

You can also read Nick’s previous articles on what if D-Day did not happen in 1944 here, what if Hitler had been assassinated in July 1944 here, and what if the Nazis had not invaded Crete in World War Two here.

Sources

- Blucher: Scourge of Napoleon - Michael V. Leggiere (2014)

- If Napoleon had won the Batter of Waterloo - G. Macaulay Trevelyan (1907)

- Napoleon: The Last Phase - Lord Rosebery (1900)

- Napoleon Wins at Waterloo - Caleb Carr (1999)

- The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo and the Somme - John Keegan (2004)

- Trafalgar and Waterloo: The Two Most Important Battles of the Napoleonic Wars - Charles River Editors (2014)