Great Britain and the United States of America have cooperated in two World Wars, the Iraq Wars and the War on Terror. When considering these military theatres it can be forgotten that these two countries have fought one-another. The War of 1812 is one such example. The growing US strength in the aftermath of the War of Independence is revealed by the two ship-on-ship engagements which I will examine. Though Britain won this war with overwhelming naval control, the USS Constitution sank two Royal Navy warships in an impressive display of seamanship.

Here, Toby Clark follows his first article in the series (here) and considers the naval battle between USS Constitution and HMS Java.

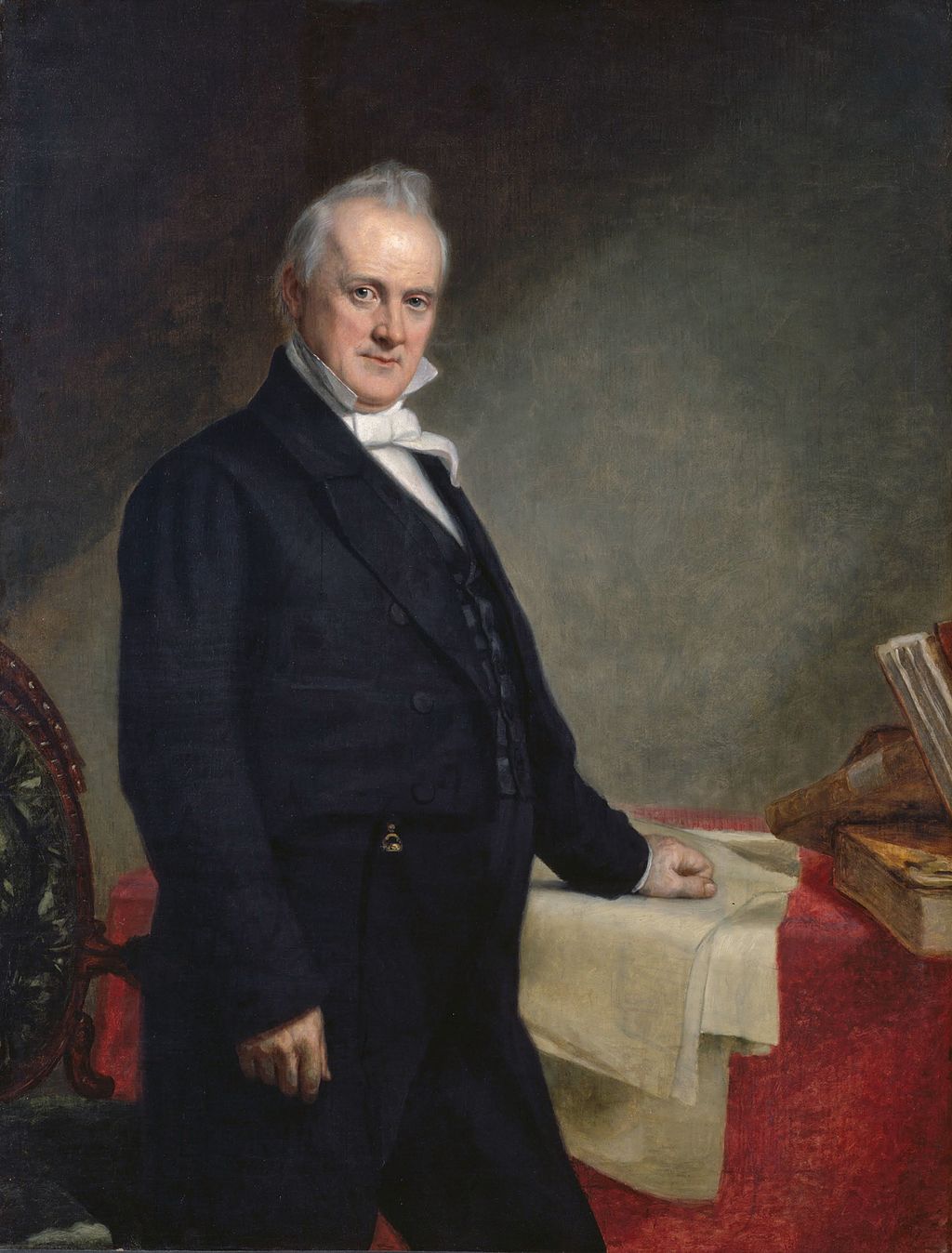

The USS Constitution and HMS Java in battle in 1812. Drawing by Nicholas Pocock.

USS Constitutionversus HMS Java

It was December and in the South Atlantic before USS Constitution caught the second British frigate. This time under the command of Commodore Bainbridge the Constitutionhad, in partnership with the much smaller USS Hornet patrolled to the port of Salvador, on Brazil’s East Coast. Leaving the Hornet to challenge the Royal Navy sloop HMS Bonne Citoyenneto a battle, Bainbridge had sailed northwards up the Brazilian coastline. The decision to leave the Hornet was taken because Bainbridge hoped that by withdrawing the Constitution, HMS Bonne Citoyennewould emerge from the port and fight. However, the Royal Navy sloop ignored the Hornet’s challenge. Ignoring a challenge might damage a ship’s reputation but HMS Bonne Citoyenne made the correct decision because her cargo contained bullion and specie, which was needed to sustain Arthur Wellesley’s Army in Spain.[1]By not fighting, HMS Bonne Citoyenne avoided USS Hornet’s Master Commandant James Laurence; the same man who would later reduce HMS Peacock to a shattered hulk but would go on to die in command of USS Chesapeake in the momentous fight with HMS Shannon.

Aside from this matter, the important engagement occurred on December 29, 1812 as Constitution sighted HMS Java. HMS Java was identical to HMS Guerriérebecause they were both French warships originally, but pressed into British service after they were captured. Such similarities meant similar weaknesses because HMS Java, like Guerriére, had 49, 18-pounder cannons, whilst Constitutionmounted 55, 24-pounder cannons.

Aboard HMS Java Captain Lambert decided to fight. This decision makes sense when we consider that Lambert was unaware of the destruction of HMS Guerriére; as communicating with ships at sea was extremely difficult.[2]The engagement began with Java chasing Constitutiontowards the open sea only for Bainbridge to suddenly turn towards the Java. Sailing parallel to one-another, Java on the left, or port and Constitution on the right, or starboard and the two ships remained out of range. Keeping the distance was certainly Bainbridge’s idea, knowing full well that 24-pounder cannon could outrange Java’s 18-pounders. By 14:00 PM Constitution andJava were ready for battle and the first shots boomed out across the calm sea; fired at long range by the Constitution these cannon balls struck the Java which was powerless to respond.

The Battle Gets Fiercer

The battle was decidedly one sided for these first forty minutes. HMS Java made efforts to close the distance between the ships but each time Lambert steered to starboard, Bainbridge drew Constitution away and as a result the British cannon could not be brought to bear. Unlike the engagement with HMS Guerriérewhich Constitution began in a poor position taking heavy fire and then concluded at short range with broadsides, here Bainbridge shrewdly chose to bombard Java without putting Constitutionin harm’s way.

Once satisfied that Java had been struck repeatedly by the heavier US cannonballs and damage sustained by the British gun crews, Bainbridge chose to bring the Constitutionalongside for the final reckoning. However, the maneuver did not go smoothly because Java was also attempting a similar move. The two ships came together with Java’s prow smashing into the rear port side of Constitution. Here was an opportunity that the British could not miss! Captain Lambert called for boarders to stream across the wooden bridge formed by Java’s jib-boom - the large mast rising above the prow - which was entangled with Constitution’s mizzen, or rear mast. This tenuous link was all the incentive the British needed as having endured an hour of maneuver where every attempt to engage was frustrated by Constitution pulling away, Lambert’s cry for boarders was eagerly answered. The pivotal moment approached as the British swept forward across Java’s deck. Faced with this charge the crew of Constitutionrose to the challenge and rapid musketry broke out from Constitution’s rigging. The British charge was doomed; not only had Captain Lambert and most of the boarders been smashed down onto Java’s deck by musket balls, the USS Constitution then pulled to starboard tearing Java’s jib-boom away and breaking free.

With the range closed, the two ships began firing broadsides. Huge crescendos filled the air as smoke, fire and iron seared the gap between the warships. Aided by her thick wooden walls and larger cannons Constitutionkept the advantage. Below decks the cannon balls ripped great holes in the wooden walls and sent splinters through the tightly packed gun crews. The carnage was worse aboard Java as 24-pounder balls blew cannon from their mounts, smashed stairways and floors, but worse of all caused catastrophic damage to Java’s masts. By 16:00 PM Javawas a hulk, with masts down, rigging and sails draped across the deck and over the sides of the hull. Most of the crew was incapacitated including Captain Lambert, who was mortally wounded, and the British gunnery dropped away to sporadic single shots. Realizing that Javawas stricken Bainbridge turned out of range to assess damage to his own ship.

Provided with time, the Java’s replacement commander, Lieutenant Chads, nailed the Royal Navy ensign to the stump that remained of the main mast and reorganized the ship. Unsurprisingly, Chads display of leadership was not enough and as the Constitution took up position for more broadsides, the Royal Navy ensign was hauled down. The time was 17:30 PM and HMS Java surrendered to USS Constitution.

The aftermath of the fight was a sorry affair; HMS Java was no longer seaworthy, 48 men were dying and 100 more were wounded. Due to Bainbridge’s decision to keep the Constitution out of range of the British guns for parts of the battle the US casualties were much lower, only 12 men being killed and 22 wounded. In this engagement with HMS Java‘Old Ironsides’ had once again protected her crew from the ravages of battle.

Analysis

The power of the Royal Navy was undisputed from 1805 until 1812 when the United States’ frigates targeted British warships. Here we see the primary reason for British defeat: unpreparedness. Professor Jeremy Black has suggested that the British warships were lacking a full complement of sailors which would reduce the frigates’ ability in battle.[3]This reduction in ability was due to the difficulty of firing and maneuvering a warship under fire without enough sailors for each role. The lack of sailors on board also suggests a lack of resources but the larger problem remains. By allowing the British frigates to patrol off the US coast whilst under-crewed shows unpreparedness because the US threat was deemed so weak that Royal Navy frigates were crewed for sailing rather than for fighting. This is demonstrated in the case of HMS Java which had an inexperienced crew as well as civilians on board. In light of these weaknesses, Phillip S. Meilinger concludes that HMS Javawas “hoping to avoid a fight”[4]which does not fit with the Royal Navy’s Nelsonian tradition of victory.

The major inaccuracy in the story is the supposed equality of the USS Constitution and the British warships that she destroyed. Firstly, the Guerriéreand the Java were smaller in size and had thinner outer-walls, added to which the British cannons fired smaller projectiles which did less damage. In the case of the Guerriérethe US frigate had another advantage because the British ship was an elderly French warship and her masts were rotten and too weak for rapid changes of direction, such as tacking into the wind.[5]In another inaccuracy, the British gunnery is downplayed to the point of ineptitude. However, aboard HMS Guerriéreand HMS Java the traditional Royal Navy excellence was in place.[6]Despite this, George Canning MP and a previous Treasurer of the Navy spoke in Parliament of how the “sacred spell of the invincibility of the British navy was broken by those unfortunate captures”. Canning went on to stress that this war “may not be concluded before we have re-established the character of our naval superiority, and smothered in victories the disasters which we have now to lament, and to which we are so little habituated.”[7]

Conclusion

The Royal Navy had lost two warships in foreign waters and this shocked the establishment. The loss of HMS Guerriére and HMS Java to a fledgling US Navy was the 19thCentury equivalent to HMS Repulse andHMS Prince of Wales being sunk by the new Japanese naval air arm in 1941. With time the British overwhelmed the United States Navy, blockaded the coastline, retained Canada, and burnt the White House. Signed on Christmas Eve 1814 the Treaty of Ghent ended the war and arguably came just in time for the United States.[8]

For historians this is the tale that is remembered; for example in his magnum opus,The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery, Paul Kennedy does not mention the US frigate victories at all. Instead Kennedy focuses upon the obvious limitations of British sea power, namely that in the future a large continental land mass like America could not be conquered by warships alone.[9]However, it remains ironic that the Royal Navy was held at bay by a warship named Constitution, evoking the document which had set North America apart from the British Empire. The British victory over the United States may have settled the relationship between the two countries, but the US successes at sea suggested an alarming future; a future which foresaw a rise of US maritime and naval power that would eclipse Britain in just over a century.

What do you think of this naval battle? Let us know below.

[1]Donald Macintyre, Famous Fighting Ships, 39.

[2]Donald Macintyre, Famous Fighting Ships, 39.

[3]Jeremy Black, A British View of the Naval War of 1812 (Naval History Vol. 22 Issue 4, August 2008, pp: 16-25)

[4]Phillip S. Meilinger, Review of The Perfect Wreck—“Old Ironsides” and HMS Java: A Story of 1812by Steven Maffeo (Naval War College Review

Vol. 65, No. 2, Spring 2012, pp: 171-172)

[5]Andrew Lambert, The Challenge: Britain Against America in the Naval War of 1812, 75-76.

[6]Andrew Lambert, The Challenge: Britain Against America in the Naval War of 1812, 77 and 99.

[7]Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, 18 February 1813:Address Respecting the War with America (Vol. 24, pp: 593-649)

https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1813/feb/18/address-respecting-the-war-with-americaDate accessed: 05/02/2019)

[8]Matthew Dennis, Reflections on a bicentennial: The War of 1812 in American Public Memory(Early American Studies Vol. 12, No. 2, Spring 2014), 275.

[9]Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London: Penguin, 2017), 139.