The source of the world’s longest river, the River Nile, had intrigued people for millennia. From the Egyptians onwards, the source remained a mystery, leading to be called “the problem of the ages”. In fact, it wasn’t until the nineteenth century when some extraordinary explorers found the great river’s source. Victor Gamma explains.

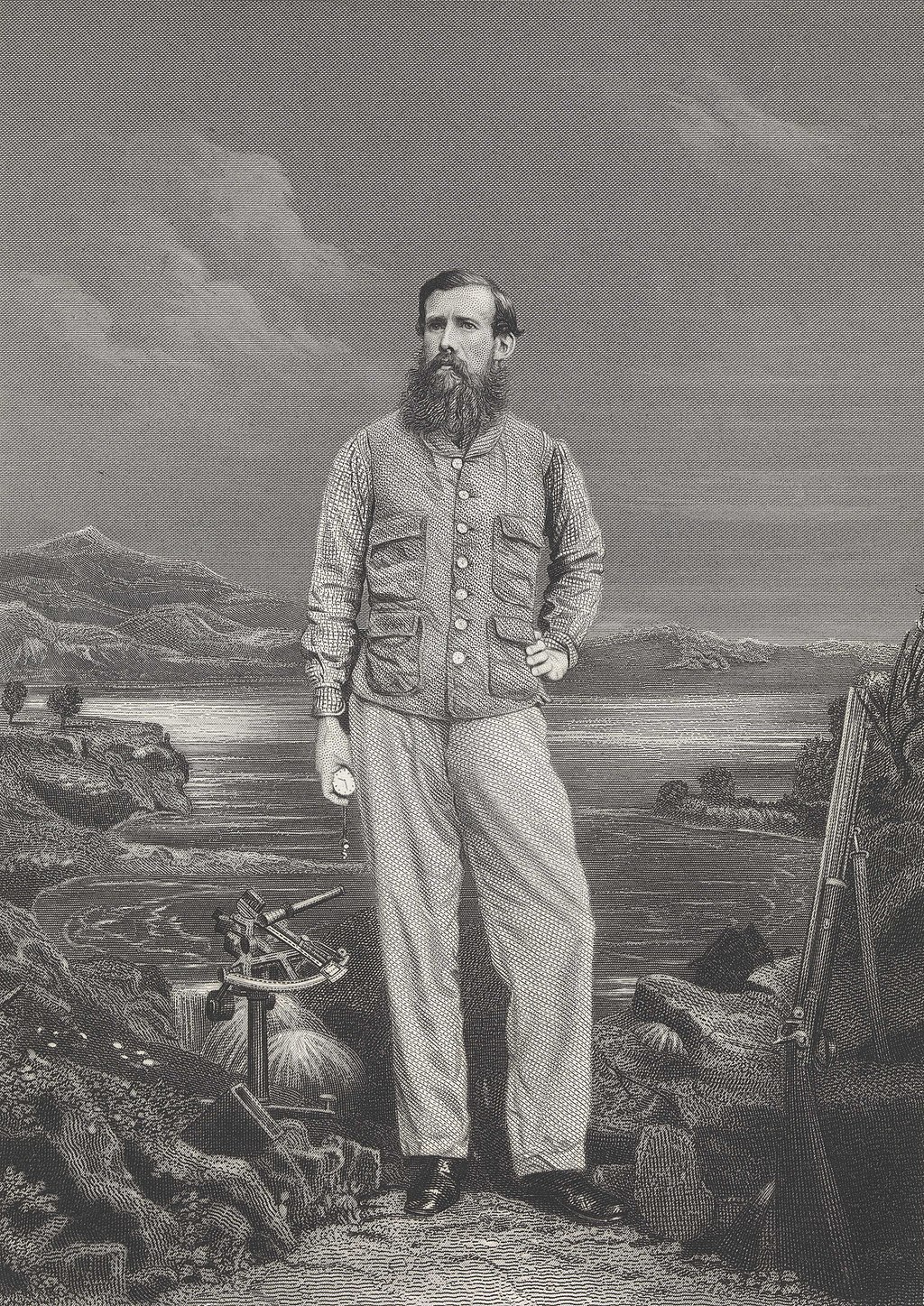

A portrait of John Hanning Speke, the man who played such a key role in the discovery of the source of the River Nile.

John Hanning Speke stared at the foamy torrents pouring out of the lake he had just named Victoria after his beloved queen. Speke smiled in triumph, and no wonder, the date was July, 28, 1862 and Speke, along with his companion James Augustus Grant was about to solve a riddle that had bedeviled the world for 2,000 years; the source of the world's greatest river, the Nile: "Here at last I stood on the brink of the Nile!", he later wrote in his journal.

It might seem strange that finding the place where a river begins would be that hard, but it was not called 'The Problem of the Ages' for nothing! In fact, the headwaters of the Nile River system have such a complicated geology that even today geographers and other scientists continue to study its labyrinth-like network of physical features and debate its source. Technically, that prize goes to a tiny spring in the hills of Burundi. This spring is amongst the headwaters that nourish Lake Victoria.

If complex geography weren't enough of a problem, think of how challenging it would be to explore that same system without the sophisticated technology and transportation that today's explorers enjoy. Traveling in that part of Africa in the mid-nineteenth century was not easy; fever, attacks by hostile locals, and desertions were only some of the problems encountered. When you realize that almost every rugged, hot, wet, scratchy, insect-infested mile was a struggle, you will understand why the discovery took so long.

Why was it so important to discover the source of the Nile anyway? The Nile River has always held a special place in humankind's imagination. To the Egyptians it was the divine basis of life itself, for without it, life was unthinkable. To them, its beginnings were lost in mystery, flowing from a land far beyond where they dared to venture, and they simply worshiped it as a god. Many later civilizations held the beautiful and marvelous culture of Egypt in wonder and could point to the Egyptians as the originators of civilized life. It is not hard to see then why, starting with the ever-curious Greeks, a quest for the source of the fabled Nile became an on-going obsession.

From Myth to Science

By the time Richard Burton and his partner Speke began their quest, two thousand years of failed attempts stretched before them. Both the Greeks and the Romans, unable to penetrate to the upper reaches of the Nile, fell back on speculation or hearsay as to the great river's ultimate origin. Puzzled Romans represented the Nile as a male god with his face and head obscured by drapery. To be fair, though, the Greek merchant Diogenes and the mathematician Eratosthenes both correctly identified lakes inland from the east coast of Africa as the Nile's source. This knowledge was noted by the great Ptolemy. But to make mention of something is one thing, to see it for oneself is quite another! For centuries after Ptolemy, the question was relegated to the realm of fable and speculation. These included the myth of Prester John and the idea that a branch of the Nile flowed into the Atlantic.

The mists of speculation began to clear up as the light of modern science and discovery shone on the question. By the mid-18th century the connection of the Blue and White Nile had been identified as well as a river meandering into Lake Tana, which we now know is the source of the Blue Nile. But it was to the Victorians that the honor of settling the "Great Question" was to be given; specifically Burton, Speke and Grant.

It would take a determined fellow to solve a 2,000-year-old riddle and these three men certainly fit the description. Speke was an officer in the Indian Army. After strenuous months of training and fighting Speke spent his furloughs not in relaxation but exploring the Himalayas and Tibet. Burton was already famous as a traveler, linguist and, shall we say, "eccentric?" Unlike the disciplined and well-mannered Speke, Burton was known to be irascible and difficult to deal with. Burton was one of those men who placed obedience to his own convictions above societal convention. His method of travel was to meld with the local population so as to be indistinguishable from them. His facility with five languages was another unusual distinction. What these two men shared, though, was an obsession for exploration and their combined talents attained one the great feats in the history of discovery.

It was Burton who invited Speke to join him in exploring east Africa. That was in 1854. Two years later, sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society, an expedition began into the interior of east Africa to locate a series of great lakes said to exist. They also, of course, were hoping to find the source of the Nile.

A Prize Gained but a Friend Lost

Their final attempt began in June 1857. This 500-mile trek was slowed not only with fever but the never-ending complications of local politics. As the expedition passed from the realm of one ruler to another great caution and skill were needed to secure permission and protection as well as to recruit guides. This involved so much gift giving and bribery that the expedition was well fleeced by the time Speke made his great discovery. Burton became so ill that he was eventually forced to stay behind while Speke forged ahead to a lake the locals called Ukerewe. This separation was to prove ominous to the two adventurers, for it meant that when Speke beheld what he believed was the source of the Nile, Burton was not there to see for himself. Burton would refuse to accept Speke's opinion. This led to a disagreement between the two men that quickly became very public and bitter.

Nonetheless, the parting of two great men of exploration did not stop the march of geographical progress. Leaving Burton behind in the Arab settlement of Ujiji, near the lake of the same name, Speke set out across this lake, now known as Lake Tanganyika, hoping it was the source of the Nile. Unable to obtain an adequate boat, Speke was forced to abandon the quest and rejoined Burton. While recuperating at Kaze, in the land of the Unyamwezi where they had stayed earlier, the locals related more tales of Lake Ukerewe to the two explorers. Illness sapped the interest that Burton would normally have had, but the stories fired Speke's imagination. With a hurriedly gathered force of men and supplies Speke set off for the fabled lake. On July 30, 1858 he reached the shores of the lake. He bestowed the name Victoria on the lake in honor of his queen. But lack of provisions and equipment forced Speke to content himself with a rough sketch of the lake and a burning conviction that he had the solution to a 2,000 year-old riddle. He returned to Kaze and presented his case to his colleague. The fever-stricken Burton, however, refused to accept Speke's conclusion. An on-going debate ensued in which the two men failed to agree. The discussion became exceedingly lively. Illness, exhaustion and divergence of temperament all played their part. The final fallout occurred when Speke, back in England, made his case to the Royal Geographical Society. Burton had remained in Zanzibar, too sick to travel but expecting that Speke would delay his announcement until Burton could be present to argue his side of the issue. Although Speke could hardly ask his sponsors to wait to hear the results of their investment, Burton saw Speke's actions as a mortal sin and never forgave him.

The Puzzle Unraveled at Last

To confirm the epic discovery, Speke returned to Africa, this time in the company of an old companion from his India days, James Augustus Grant. Having learned his lesson from earlier attempts, Speke and Grant assembled a well-provisioned expedition of 200 men before setting out in 1860. Nonetheless, the usual delays of travel in Africa at that time caused interminable delays. It would in fact be two years before Speke arrived at his longed-for destination. But when Speke heard of a river that flowed out of Lake Victoria, nothing could stop him from reaching for what men had dreamed of so long. Leaving the fever-stricken Grant behind to rest, he explored Lake Victoria and found the rapids where a river left the lake and fed the Nile.

Rejoined by Grant and accompanied by another associate from the Indian service, hunting-enthusiast Samuel Baker, Speke then began a descent of the Nile. Upon reaching Khartoum, Speke wasted no time in sending a now famous telegram to London. The terse but momentous message read simply, "The Nile is settled." Upon his return to England, Speke received full credit and plaudits for his accomplishments. Like Columbus, John Hanning Speke's moment of triumph was short-lived. Only two years later, in a tragic postscript, and on the day before he was to face his old colleague and enemy Burton in a debate over the Nile question, Speke was killed in a hunting accident. He was 37.

Final confirmation of the source of the Nile was to wait until 1875. It was then that Henry Morton Stanley, of "Dr. Livingstone I presume" fame, circled Lake Victoria and confirmed Speke's claim. Grueling determination, suffering and imagination had solved another age-old mystery.

What do you think of the explorers who confirmed the source of the Nile River? Let us know below.

References

Southwaite, Leonard, Unrollingthe Map: The Story of Exploration,The Junior Literary Guild, New York, 1930, pages 253-8

(February 4, 2010) "Speke and the Discovery of the Source of the Nile: An Introduction." [Web blog post], https://www.faber.co.uk/blog/speke-and-the-discovery-of-the-source-of-the-nile-an-introduction/