William McKinley was the 25th president of the USA - from 1897-1901. While before becoming president his political career was focused on Ohio, there was a status of McKinley in Arcata, California until it was toppled in February 2019. Here, Victor Gamma returns and looks at the case for and against the removal of the statue. In part 4, we look in depth at McKinley’s character and domestic life.

If you missed it, in part 1 here Victor provides the background to the statue removal, in part 2 here he looks at McKinley’s relationship with Native Americans, and in part 3 here he considers McKinley’s relationship with African Americans.

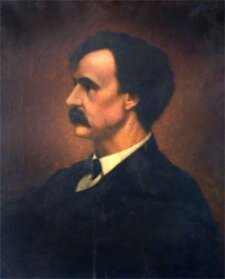

A photo of William McKinley.

The word included in the accusations brought against the man: “rape, murder, genocide, savagery” would be a good description of a serial killer or monstrous dictator like Hitler. But they are wildly inconsistent with the known character of William McKinley. The testimony of those who knew the man are universal in their admiration of his personal habits. In 1896 when a McKinley run for president became likely, the opposition mudslinging kicked into high gear. The problem was, they could find nothing to attack him on. His life was free from scandal, he was a hard worker. He had not used his office to enrich himself. The opposition then resorted to digging up falsehoods.

In fact, the general respect with which this man had garnered from public opinion is well illustrated from an incident occurring in 1893. In that year of financial panic, McKinley, through no fault of his own, faced bankruptcy. His debts far exceeded his ability to repay and so he considered quitting politics and returning to practice law. When his desperate straits became public knowledge, a great outpouring of public sympathy arose. As many as five thousand donations, many from Democrats, poured into the Governor's office. The reason? His reputation for kindness and as an honest public servant who never used his office for public gain. The Democrat Brooklyn Eagle described the entire affair, both the bankruptcy and the generosity of friends in coming to McKinley’s assistance as “a matter of hearthstone pleasure around the land.”

Honest politician

To those who say an honest politician doesn’t exist, I say, meet William McKinley. Even in that era when people took religion seriously, he stood out as an example of a complete Christian gentleman. He is, in fact, considered to be one of the most devout men to ever occupy the White House. He was a lifelong and pious member of the Methodist Church. As a holder of public office, he would often pray before making important political decisions. His soul-searching about what to do with the Philippines is not atypical. On that subject he said to a group of visitors: “I walked the floor of the White House night after night, until midnight. And I am not ashamed to tell you gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed to Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night.” He disapproved of off-color jokes or stories in his presence. As president of the local Y.M.C.A. he mentored young men to take their devotion to spiritual and moral standards seriously and led them in street-witnessing outings. McKinley characteristically proclaimed his spiritual convictions publicly, “Our faith teaches that there is no safer reliance than upon the God of our fathers, who has so singularly favored the American people in every national trial, and who will not forsake us so long as we obey His commandments and walk humbly in his footsteps.” I believe the record of his life, as witnessed partially in this article, provides abundant examples of the fact that his life and actions as a political leader were amply informed by his religious convictions.

Broad-minded

Next, evidence is abundant of his basic broad-mindedness. In the words of one biographer, “McKinley was devoid of bigotry…” For instance, although a dedicated member of the Methodist Church all his life, his creed based itself on the love and kindness of God, not doctrinal bickering. In contrast to a rising tide of anti-Catholicism, he consistently embraced into his circle of friends and into his administration followers of all creeds, including Catholic. His choice as Commissioner-General of Immigration was an Irish Catholic labor leader named Terence Vincent Powderly, founder of the Knights of Labor. At the presentation of the sword to Admiral Dewey on October 3, 1899, McKinley took the unprecedented step of having a Roman Catholic prelate, Cardinal Gibbons, pronounce the benediction. Despite his strict Methodism, he made many friends among the Catholic community of Canton.

Kindred to this, his attitude toward labor further underlined his humanity. Although a Republican and decidedly pro-business, he managed at the same time to be a friend of labor. This was no easy feat during the ‘Gilded Age’. Conflict between labor and the corporate interests was so intense at this time that some were afraid it would lead to a new civil war. Despite this, McKinley managed to win the support and respect of both sides. He understood the importance of a healthy business environment while at the same time sympathizing with the grievances of labor. His popularity with labor dates from an early court case in which he defended some miners who had been involved in a riot. He managed to get all but one acquitted. When the strikers scraped up money to reimburse him, McKinley refused to accept payment from the struggling miners. Numerous measures passed for the protection of workers during his tenure as governor of Ohio show his influence. He often took it upon himself to arbitrate labor disputes, attempting to win settlements favorable to both sides. When he did so, he insisted that his involvement be kept private.

Dedicated public servant

By all accounts McKinley was a dedicated public servant. As president, he rarely took vacations. In 1898, a very taxing year involving major foreign policy crises, he took one holiday lasting one week. Part of it was spent visiting a military hospital to check on conditions and encourage the sick and wounded. Intense pressure brought on by the Spanish-American War and scandals over the War Department would have driven a lesser man to frequent vacations - not the sober McKinley. Contrast this with the frequent vacations taken by recent presidents. During that war, which McKinley had done everything he could to avoid, he was governed by the rule he articulated to his Secretary of War, Russell Alger. The Secretary was eager to deflect negative publicity and cater to growing demands from militiamen who feared the war would end before they had a chance to see action. To accomplish these ends he proposed to the president an immediate attack on Puerto Rico. McKinley answered with his usual terse practicality and high standards, “Mr Secretary what do you think the people will say if they believe we unnecessarily and at great expense send these boys out of the country? Is it either necessary or expedient?”

Eyewitnesses also reported that the Major was devoid of pretense or self-importance no matter how high he rose in the public service. Both in speech and appearance he “showed no sign of self-importance or affectation” in Leech’s words, and was always accessible to the general public. He often insisted that his participation in certain accomplishments be kept out of the paper for he had “no desire to indulge in any pyrotechnics.” His attitude toward public service can be summed up in the following statements taken down by his secretary George Cortelyou, “when the time comes the question of my acquiescence (to re-nomination in 1900) will be based absolutely upon whether the call of duty appears to me clear and well defined.” Since McKinley was not known for empty platitudes, we can take these statements at face value.

Domestic life

In domestic virtues McKinley developed a reputation which approached the legendary. He married Ida Saxton on January 25, 1871. The marriage was sadly destined to have its share of tragedies. Two daughters were born to the couple, both of whom died in early childhood. The sad little graves of Katie and Ida McKinley can be seen in the McKinley Memorial in Canton, Ohio. McKinley’s wife never quite recovered from this double blow and was a semi-recluse for the rest of the couples’ marriage. As author Margaret Leech put it “The pretty, pleasure-seeking young woman McKinley had married had changed to a feeble, self-centered nervous invalid.” Much of the Major’s time was spent tending to his wife during her frequent bouts of illness and seeking respite by sending her to various cures. Ida could also be rather demanding. Many official meetings were interrupted by her insisting her husband leave the meeting immediately and tender his views on some domestic matter. Common themes were his opinion on which fabric to use in creation of some item of clothing or decor. The disgruntled participants of the meeting were surprised to see McKinley immediately leap up to go to his wife at these summonses. To many his wife’s solicitations seemed trivial, but McKinley invariably gave her his full and careful attention. Unlike many men in his circumstances, the Major never gave in to complaint or the seeking out of other female companionship. Instead, many observed him change to accommodate his wife. He was observed tirelessly ministering to her needs and attentive to her comfort. His tone of voice became soft and careful, he developed skill in diverting Ida, he endured close, stuffy environments because she avoided fresh air, he adjusted his gait to suit her hesitant pace. He became expert at diagnosing the degree of severity of her attacks and treating them. His example of domestic constancy was one factor in winning the support of women, who, although they lacked the suffrage at this time, were playing an increasingly important role in social and political issues. After decades of marriage he continued to sign his letters to her “your faithful husband and always your lover.” During the White House years, so devoted was the president to the First Lady that Senator Mark Hanna remarked that McKinley's dedication to her was “making it awfully hard on all the other husbands around here.”

Quotes on McKinley

But instead of relying on our distant voices alone, let us allow those who knew him to speak. The following are a series of quotes.

He was “a mediaeval knight in the dusty arena of Ohio politics” - Bellamy Storer.

“He never had a harsh word, but rather a kindly appeal: ‘Come now, let us put the personal element aside and consider the principle involved.’ “ - Robert La Follette.

“That never failing remedy of yours.” -- Mark Hanna on McKinley’s famous tact.

"In a few minutes word came from Mr. McKinley that he would see me. How any man can see so many people ... and still keep himself calm, patient, and fresh for each visitor in the way that President McKinley does, I cannot understand. - Booker T. Washington

McKinley Quotes:

“This seems to be right and fair and just. I think so don’t you?” (To Mark Hanna)

“There are some things … I would not do and cannot do, even to become President of the United States.”

“War should never be entered upon until every agency of peace has failed; peace is preferable to war in almost every contingency.”

This brings us back to the accusations. Bearing in mind that this article is by no means an exhaustive description of the admirable character of our 25th president, ask yourself, does William McKinley sound like someone who would be guilty of “racism, murder and slaughter” or willing to tolerate the enslavement and abuse of anyone? Or has he been most grievously misrepresented?

Having read the series, what do you think of William McKinley? Let us know below.

Now, if you want to learn about Tudor England, you can read Victor’s series on Henry VIII’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon here.

References

The Booker T. Washington Papers, Vol. 5: 1899-1900, University of Illinois Press, 1976.

“Conflict Among the Tribes and Settlers.” Nebraska Studies.org

Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of William McKinley, Lawrence: Regents Press of Kansas, 1980.

Gould, Lewis. “William McKinley Domestic Affairs.” 2019, miller center.org, accessed October, 2020.

Harpine, William D. “African American Rhetoric of Greeting During McKinley’s 1896 Front Porch Campaign.” University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Communication Department 2010.

Leech, Margaret, In the Days of McKinley, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1959

McKinley, William, First Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1897.

McKinley, William, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1897.

McKinley, William. “Veto Message to Congress.” May 03, 1900.

“William McKinley and Civil Rights” Presidential History Geeks, Oct. 13th, 2011, potus-geeks.livejournal.com, accessed October, 2020.

Marshall, Everett, Complete Life of William McKinley and Story of His Assassination An Authentic and Official Memorial Edition, Containing Every Incident in the Career of the Immortal Statesman, Soldier, Orator and Patriot, Originally published by Donahue, 1901

Morgan, H. Wayne, “The View from the Front Porch: William McKinley and the Campaign of 1896" presented to the 12th Hayes Lecture on the Presidency, February 18, 2001, in the Hayes Museum auditorium.

“Patterns of White Settlement in Oklahoma” Region 3 Oklahoma Historic Preservation Survey, Oklahoma State University, 1986.

Washington, Booker T. Up From Slavery, An Autobiography, New York: Doubleday, 1901.