In a letter to Horace Greeley in August 1862, President Abraham Lincoln declared that his ‘paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery’.[1] Yet by the end of the American Civil war the enslavement of blacks had been formally abolished thanks in part to legislation such as the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as the post-war 13th Amendment to the Constitution. In popular memory, the man responsible for these great changes to American society is Lincoln; remembered as the ‘Great Emancipator’ and depicted as physically breaking the shackles binding African Americans to their masters. Though it is true enough that the inauguration of this Illinois statesman and his Republican administration provided Southern slave owners with an excuse to push for secession and defend their property from what they claimed to be an imminent threat, Lincoln was very clear in his presidential campaign and at the outset of his presidential term that his aim was not to touch slavery where it already existed, but simply to prevent its expansion. Was the President, therefore, as integral to the demise of black enslavement as has been suggested?

If the role of Lincoln as the driving force is to be questioned, it follows to ask what other influences were at play. More recently, some historians have done just this. In the wake of the social and political upheaval of the later 20th century, the American academy has produced a ‘new social history’, of which has led to a separate branch of Civil War historiography looking to the role of the slaves themselves in securing their own freedom. Historians such as Ira Berlin have emphasized the grass-roots movement of black slaves during the war, and their personal fight for freedom through escaping to Union territory and challenging the status quo. However, it is difficult to view these historical people and events in complete isolation. Thus, in this essay, I will examine the actions of slaves in conjunction with that of the Union army and also the administration in order to illustrate how the process was more complex and multi-layered than simply one person, or one group, as the harbinger of emancipation.

Slaves and the Escape to Union Lines

Slaves were far from the passive and docile creatures that some pro-slavery activists liked to suggest. A steady trickle made the passage North even before the Civil War began, where their presence shaped the anti-slavery activities of white northern men. Frederick Douglass, for example, was a former slave who had managed to escape from his southern house of bondage in 1838. Douglass brought a unique perspective that would influence the abolition movement since he was able to express the hardships of enslaved blacks, as well as demonstrate the intelligence and capabilities of African Americans to northern audiences.

It was during the Civil War, however, that the number of slaves running away from their masters reached its peak and was largely based on the knowledge that refuge could be sought within the lines of the Union army. Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act, those who escaped to ‘free soil’, non-slaveholding regions, were considered to have self-emancipated; during the war, proximity to free soil was increased as the Union lines crept further and further south.[2]

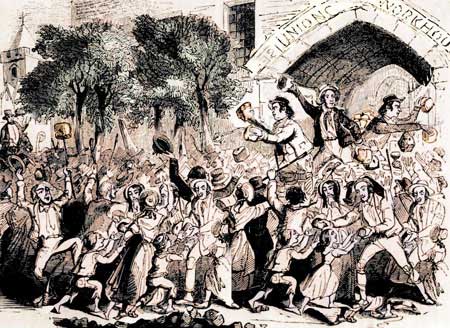

From the outset of war, thousands of African Americans flooded Union camps, sometimes in family units, and left army generals wondering how they should respond. After entering Kentucky in the fall of 1861, General Alexander McDowell McCook appealed for guidance from his superior, General William T. Sherman, on how he should respond to the arrival of fugitive slaves. McCook worriedly declared to Sherman that ‘ten have come into my camp within as many hours’ and ‘from what they say, there will be a general stampeed [sic] of slaves from the other side of Green River.’[3] General Ambrose E. Burnside faced a similar situation in March 1862, describing how the federally occupied city of New Bern, North Carolina, was ‘overrun with fugitives from surrounding towns and plantations’ and that the ‘negroes…seemed to be wild with excitement and delight.’[4] Such encounters would continue throughout the war as slaves made the decision to leave behind their life of enslavement for the hope of a better life with the advancing ‘Yankees’.

The Union Army: Active and Passive Advocates of Emancipation

Though it is clear that slaves made the personal decision to runaway, it was one that was facilitated by the context of war. While there were exceptions to this, including stories of slaves found hiding in swamps only 100 feet from their master’s homes, most had a destination in mind when they fled. Archy Vaughn’s escape is a case in point. One spring evening in 1864, Archy Vaughn, a slave from a small town in Tennessee, made a potentially life-changing decision. As the sun went down, Vaughn stole an old mare and travelled to the ferry across the nearby Wolf River, hoping that he would be able to reach the federal lines he had heard were positioned at Laffayette Depot. Unfortunately for the Tennessean slave, luck was not on his side. Caught near the ferry, he was returned to his angry master, Bartlet Ciles, who decided that an appropriate form of punishment for such misbehavior was to castrate Vaughn and to cut off a piece of his left ear. [5] In spite of the barbaric outcome, that Vaughn was hoping to ‘get into federal lines’ is demonstrative of how many slaves departed plantations on the basis that they would be able to seek refuge within the lines of the Union army.[6]

Indeed, the role of the Union army was crucial to the shaping of the future of fugitive slaves. Though this took various shapes and forms, it is a contribution that makes it impossible to view the road to freedom as one that slaves traversed alone and unaided. Some generals took a pragmatic approach to the situation they faced when entering slave-holding territory. General Benjamin Butler and his ‘contraband’ policy are noteworthy in this instance as examples of the army capitalizing on the events of the war. In July 1861, General Butler wrote a report to the Secretary of War detailing his view on how runaway slaves should be treated by the Union army which would become known as Butler’s ‘contraband’ theory. Here he made an emphatic resolution, decreeing that in rebel states, ‘I would confiscate that which was used to oppose my arms, and take all the property, which constituted the wealth of that state, and furnished the means by which the war is prosecuted.’[7] Hinting at the two-fold benefit of adding to the workforce of Union troops and damaging the rebellion’s foundation simultaneously, Butler’s theory that fugitive slaves were ‘contraband’ was the first to explicitly express the potential gains to be made from legitimizing the harboring of ex-slaves.

Other generals were more vocal of their hatred towards slavery, and more aggressive in the tactics they employed. One incident was General John C. Frémont’s proclamation of August 30, 1861, which placed the state of Missouri under martial law, decreed that all property of those bearing arms in rebellion would be confiscated, including slaves, and that confiscated slaves would subsequently be declared free.[8] Frémont’s proclamation at this stage in the war was provocative and quite blatantly breached official federal policy; slaves could be emancipated under martial law when they came into contact with Union lines, and this had certainly not been the case here.[9] Lincoln ordered that the general rescind the proclamation, but its initial impact was not lost, for it had signaled the possible direction that the focus of the conflict could be turned toward, and substantiated southern beliefs that the northern war aims were centered around an impetus to rid the nation of the evils of slavery.

Frémont was not alone in pushing the legal and political boundaries set by the administration, and similar occurrences repeated themselves throughout the war. Even when blocked by Lincoln, as in the case above, abolitionist Union officers were essential in the changing direction of the war. Whilst not all Union troops were politically motivated, the combination of those realizing the value of slaves in bolstering the war effort and those of an anti-slavery persuasion like General Frémont was an effective tool in aiding and sustaining the freedom of slaves across the United States.

The Republican Administration and Emancipation

In studying the response of the Union military it is easy to come to the conclusion that the federal government often lagged behind or was slow to respond to what was already happening within the Union army, or even that they were less supportive of the plight of the slaves during the war. Indeed Lincoln and his administration are often criticized on their attitude towards making the Civil War a war to free the slaves, particularly by historians who place the responsibility of slave emancipation on the efforts of the slaves themselves. Berlin describes the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation as ‘a document whose grand title promised so much but whose bland words delivered so little’, and further states that it freed not a single slave that had not been freed under the legislation passed by Congress the previous year in the Second Confiscation Act.[10] First of all, that the First and Second Confiscation Acts were the products of the administration should be noted. The Second, as referenced by Berlin, declared that any person who thereafter aided the rebellion would have their slaves set free.[11] Secondly, the notion that the Emancipation Proclamation was in essence no more than a grandly worded document without any backbone is false when it is understood how the proclamation’s inclusion of black conscription had wider repercussions for the Union military effort and the attainment of black freedom. Though examples of blacks serving in the military are visible before Lincoln’s proclamation, for instance Jim Lane’s 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry formed in 1862, the new federal policy made this a much more frequent occurrence. This is also to say nothing of the emotional and moral impact such a document made on the psyche of the African American community.

Though it can be conceded that the Emancipation Proclamation positively contributed to emancipation efforts, it would be wrong to claim as James McPherson does that Lincoln played ‘the central role’ in ending the institution of bondage.[12] The same is true for evaluations of subsequent abolitionist legislation, notably the Thirteenth Amendment. Oakes’ emphatic declaration that the amendment, which formally prohibited slavery across the United States, ‘irreversibly destroyed’ slavery is correct in highlighting the importance of an anti-slavery constitutional amendment but simultaneously overshadows the role played by non-political actors in the fight for freedom.[13] The movement of slaves towards federal lines and the protection they were then given is surely comparable to the effects of the Thirteenth Amendment, despite being described by Carwardine as ‘the only means of guaranteeing that African Americans be “forever free”.’[14]

Instead, as this essay has demonstrated, the freeing of slaves during the Civil War is best understood as a multi-layered, interactive process. Slaves were not passive participators; they could and would act on the opportunities to leave behind a life of slavery for one of freedom. Though things might not always go to plan, as Archy Vaughn’s violent tale illustrates, the impetus to leave among enslaved African Americans was strong. Nevertheless, they did not free themselves. The action of slaves alone was not enough to ensure freedom, and the slaves themselves knew this. The decision to seek refuge with the federal army is indicative of how slaves predicated their choice to leave from the very beginning on the support of Union military power. Members of the federal forces were also not passive agents in the emancipation journey. While General Frémont, for example, may have identified the need to destroy slavery from the very beginning of the conflict, by the end of the war there was a shared sentiment among the Union forces that the use of ex-slaves in the fight against the South, menial tasks and armed battle included, was a vital component of the war effort. The federal administration realized this too; implementing policies that further aided and legitimized the support given by the army to slaves, as well as enhanced the contributions made by slaves to the achievement of Union victory. Slaves were freed, therefore, through the interaction of the mutually reinforcing interests of fugitive slaves and the Union war effort. It was this collaboration that enabled the mutually beneficial outcome in which the Confederacy was defeated at the hands of an emancipating Union vanguard.

Did you find this article fascinating? If so, tell the world. Share it, like it, or tweet about it by clicking on one of the buttons below…

1. To Horace Greeley, 22 August 1862 in Roy P. Basler (ed.), The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953-1955) v, 389

2. James Oakes, Freedom National: the Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: London, 2013), pp. 194-96

3. Ira Berlin et al (eds.), Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War (New York, 1992), pp. 13-14

4. Ibid., pp. 35

5. Ibid., pp. 112-113

6. Ibid., pp. 113

7. General Butler’s “Contrabands”, 30 July 1861 in Henry Steele Commager and Milton Cantor (eds.), Documents of American History, 10th edn (New York, 1988) i, 396-97

8. Frémont’s Proclamation on Slaves, 30 August 1861 in Commager and Cantor (eds.), Documents of American History, i, 397-98

9. Oakes, Freedom National, pp. 215

10. Berlin, ‘Who Freed the Slaves?’, pp. 27-29

11. Second Confiscation Act, 17 July 1862 in United States, Statutes At Large (Boston, 1863) XII, pp. 589-92

12. James McPherson, ‘Who Freed the Slaves?’ in Drawn with the Sword (New York: Oxford, 1996), pp. 207

13. Oakes, Freedom National, pp. xiv

14. Carwardine, Lincoln, pp. 228