The Deep South has a history of racial animosity, but what happened when somebody tried to unite whites and blacks? Well, in Great Depression era Atlanta, Angelo Herndon tried to do just that. And he did so as a committed Communist. Bennett H. Parten returns to the site and explains what happened when the authorities tried to prosecute Herndon under an antiquated law…

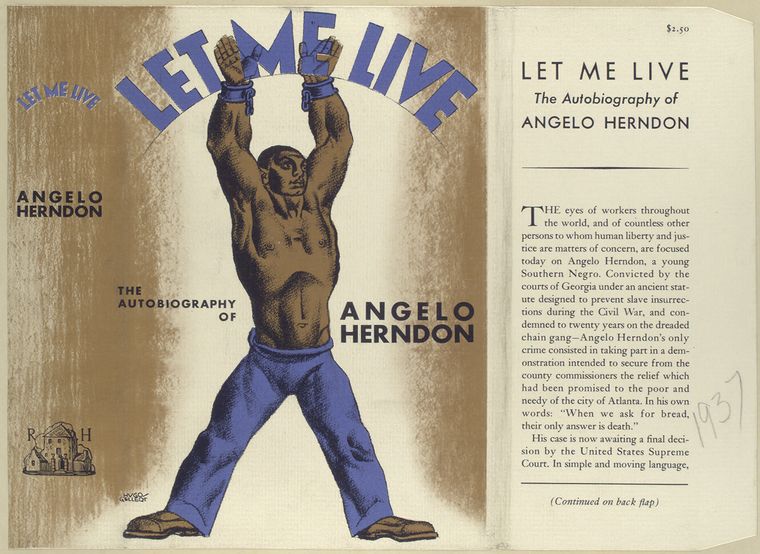

General Research Division, The New York Public Library. (1926 - 1947). Let me live : the autobiography of Angelo Herndon. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47db-d7dc-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Atlanta, Georgia is an anomaly, if not an oxymoron. It’s a commercial and industrial oasis in the middle of an agricultural desert, a regional capitol with an international profile, and an emblem of the Old South with an insatiable appetite for modernity. In the early 1930s, the city’s exceptionality emerged again as it somehow juggled being both a hub for Communist activity and a bastion of conservatism. The city, sadly, could only juggle this thorny coexistence for so long.

Fueled by civic boosterism and an influx of Northern capital, Atlanta experienced a period of rapid growth during the first few decades of the 20th century; however, the dawning of the Great Depression brought the engines churning industrial development to a screeching halt. As a result, unemployment lines swelled, the number of homeless grew, and wages were cut, leaving many to survive off of the city’s limited relief budget.

Enter Angelo Herndon. Born in Ohio, Herndon arrived in Atlanta by way of Kentucky and Alabama. While working for the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company in Birmingham, he was exposed to Communism through various labor organizers drifting through the Deep South. Officially joining the party in 1930, Herndon became an organizer and gained a degree of notoriety in Alabama, prompting a string of arrests and his eventual migration to Atlanta.

A volatile city

By the time he arrived in 1932, Atlanta’s relief situation had reached boiling point. The city’s relief budget was exhausted and payments were suspended. A number of citizens pushed the county commissioners to alter the budget so that there was more relief funding, but a number of commissioners believed the level of suffering in the city had been exaggerated, demanding that evidence of such hunger and starvation be proven before altering the budget. In a show of force, Herndon organized and led a “hunger” march on the courthouse in Atlanta that, by the time it was finished, accrued close to 1,000 angry workers demanding a continuation of the relief payments.

Never before had the city seen such a concerted statement on behalf of its working men and women. The march frightened Atlanta’s conservative commercial elite, revealing to them just how volatile and unstable the city had become. What frightened them the most, however, was the social make-up of the marchers. Poor whites as well as poor blacks marched step by step with one another, breaking Jim Crow South’s rigid social hierarchy. Interracial class solidarity on the part of the working men and women would, in the eyes of the business elite, only breed more discontent and challenge the city’s traditional conservative political leadership.

Their response was to simply destroy the movement by attacking where they believed it began: the Communists. Atlanta police began targeting suspected organizers and kept a watchful eye on the post office since the only piece of evidence on the leaflets used to announce the protest was a return address marked P.O. Box 339. Eleven days after the march, on July 11, 1932, Angelo Herndon was arrested while retrieving mail from the box in question.

Herndon was formally charged by an all-white grand jury with “attempting to incite insurrection” under an old statute originally designed to prevent slave insurrections. He received legal counsel from the International Labor Defense, better known as the ILD, whom placed noted Atlanta attorneys Benjamin Davis Jr, the son of a prominent Atlanta newspaper editor and Republican politician, and John Geer at the head of the Herndon case. The two young black lawyers designed a defense that sought to attack the constitutionality of the antiquated insurrection law and Georgia’s judiciary system by calling into question Georgia’s informal practice of excluding African Americans from serving on juries; Herndon’s defense would thus be one that would attempt to strike a major blow to the justice system’s role in preserving Georgia’s Jim Crow laws in addition to exonerating Herndon.

The trial

But Georgia’s seasoned justice system would not go down without a fight. As the trial commenced, the defense team set its sights toward the legality of all-white grand juries like the one that indicted Herndon. All of the witnesses testified that there had not been a black participant on a grand jury in recent memory, but in the absence of proof that African Americans had been systematically excluded, Judge Wyatt, whom Davis had said “used the law with respect to Negroes like a butcher wielding a knife to kill a lamb,” would not be moved (Davis 62-63). The legal team left the courtroom after the first day in an air of defeat.

The second day started off much better for the defense. The duo of Greer and Davis, with the help of attorneys A.T. Walden and T.J. Henry, launched an attack on the prospective jurors, getting one to confess to Ku Klux Klan membership. The team eventually landed on twelve jurors deemed suitable. The charge of insurrection was then debated. Atlanta policemen Frank Watson was the first to testify, reading off a list of items found in Herndon’s room. The list included rather harmless materials such as membership and receipt books, but Herndon did possess two books, George Padmore’s The Life and Struggles of Negro Toilers and William Montgomery Brown’s Communism and Christianism, that emphasized the Communist Party’s policy of self-determination for the South’s “Black Belt”, a stretch of land in the heart of the Deep South that housed large numbers of African Americans. The prosecutor, accompanied by a large map of Georgia, pointed out to the jury that under this policy a large majority of the state would fall under black political leadership, all but destroying the state’s white political stranglehold. But even with this evidence, Davis’s cross examination of Watson revealed that Watson never actually witnessed Herndon distribute radical literature or give a speech with revolutionary intent; Watson had merely seen Herndon checking his mail.

When Angelo Herndon took the stand, the momentum won with the Watson cross-examination again shifted away from the defense. In the witness stand, Herndon unleashed quite an oration, one more idealistic than inflammatory. He unabashedly emphasized the interracial aims of the party, pointing out the immense levels of suffering of both poor whites and poor blacks. He described the horrid conditions of the Fulton County jail, claiming that he had to share a jail cell with a dead man whom was denied proper medical treatment. His most radical claims, though, were made when he blamed the capitalist regime for race baiting, constantly pitting white versus black as a substitute for the natural animosities between the rich and the poor. Needless to say, Herndon’s own testimony did not do him any favors with the jury.

Closing the trial

As for the closing remarks, each of the four attorneys—two defense counselors and two prosecutors—took turns. When it came time, Benjamin Davis, vaunted for his oratory skills, released an emotional critique of the justice Herndon had been served. He charged that Herndon had simply been attempting to better the conditions of Atlanta’s working people in a peaceful way as the march on the courthouse was not violent nor did it cause any harm. According to Davis, Herndon was charged not for inciting insurrection but for being black, and his attempts to unite both races for the common welfare should be lauded. Davis’s remarks drew ire from the whites in the courtroom as well as those in the jury. Whenever he approached the jury box during his summation some of the jurors refused to listen and turned their backs on him. Davis, unfazed, went on. He read from one of the radical pamphlets found in Herndon’s possession that described the lynching and burning of a pregnant black woman. The description was so graphic and Davis’s dramatization so intense, one spectator fainted.

His summation hinged on the inherent irony of supposed “justice” in Georgia: a peaceful interracial Communist protest was condemned as insurrectionary while the justice system turned a blind eye to lynchings and other forms of racial oppression. He concluded his remarks by stating that if a guilty verdict was served, it would be derived only from the “basest passion of race prejudice”, and such a verdict would be “making scraps of paper out of the Bill of Rights” and the Constitutions of both the United States and Georgia (Herndon 351-354). Sadly, such an impassioned plea for justice was rendered fruitless as the white jury found Herndon guilty as charged.

But the battle was not over. Almost immediately, Davis and company submitted their appeal. Over the course of five years, their appeals garnered almost no headway at the national or local level. Finally, in 1937, with his case in the national spotlight—and Let Me Live, Herndon’s newly published autobiography on the bookshelves of civil libertarians and liberal thinkers nationwide—the Supreme Court struck down Georgia’s insurrection stature, arguing that it violated the First Amendment. Herndon was exonerated, and Georgia, a bastion of white conservatism, was forced to release an avowed Communist and radical interracial labor organizer. Jim Crow obviously did not die with Angelo Herndon, but his victory stood as a major blow to conservative Georgia’s ability to deal out so called “justice” in the courtroom.

Did you find this article thought provoking? If so, tell the world! Share it, like it, or tweet about it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

Bibliography

Davis, Benjamin J. Communist Councilman from Harlem: Autobiographical Notes Written In A Federal Penitentiary. New York: International Publishers, 1991.

Hatfield, Edward A. "Angelo Herndon Case." New Georgia Encyclopedia. 03 December 2013. Web. 30 June 2015.

Herndon, Angelo. Let Me Live. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Martin, Charles H. The Angelo Herndon Case and Southern Justice. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976.