DETERMINATION

When Al Smith was nominated by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) for a second presidential run in 1928, Roosevelt was again approached about running in the New York gubernatorial campaign. Committed to his full recovery—and even more dubious about the Democrat’s chances of success in 1928 then he was in 1924—Roosevelt was determined to stay out of the political race, or so he thought.

Roosevelt returned to his beloved Warm Springs after delivering Smith’s nomination speech in Houston. He was barely settled into his routine at the Georgia hideaway before he was summoned to New York City by the DNC. For the next three months, FDR remained on the periphery of the Smith campaign. Finally, in late September, Roosevelt escaped back to Warm Springs. He needed to get away, as much for his health as to avoid the importuning politicians who were already harassing and cajoling him to run for governor of New York.[1]

Howe agreed with Roosevelt’s decision not to run for three important reasons. First, he concurred with Roosevelt’s concern for his health. The second reason was their mutual awareness that FDR might be defeated. Third, they “felt that 1928 was too early for [Roosevelt] to run again for office.”[2] Smith implored Roosevelt on multiple occasions to reconsider his candidacy and each time Roosevelt remained unwavering in his opposition.

Once situated in Warm Springs, Roosevelt began taking increasing steps to “deliberately cut himself off from communication with” the Democrat delegates in New York that were pushing him to accept the nomination.[3] Eleanor, who had remained in New York was under pressure from the delegates to convince him to run. She held out until October 1, when she finally agreed to help Smith get in contact with her husband.[4] In the conversation that followed, Smith brought all the force he could bear against the reluctant Roosevelt. Finally, the combination of Eleanor’s tacit endorsement of his nomination, John Raskob’s promise to financially maintain the Warm Springs Foundation, and Smith’s decision to frame his plea on a personal basis, Roosevelt, at last, began to buckle.[5]

Smith and the DNC believed that without Roosevelt, he had no chance of carrying New York in the general election, and if he did not carry New York, then he had no chance of securing the electoral votes needed to win. Roosevelt argued against this line of reasoning, but once Smith had made the matter personal, Roosevelt knew that if he refused, he would likely lose the support of Smith and his political machinery in all future endeavors. As the conversation came to its conclusion, the exasperated Smith was nearly shouting into the phone. He asked whether Roosevelt would “actually decline to run if nominated.”[6] At this FDR waivered. He told Smith that if the convention, in full knowledge of his wishes, chose to nominate him, then he was unsure what he would decide. Roosevelt might as well have announced that he wanted to be drafted. For Smith, the effect was the same.

The very next day, FDR was nominated by the convention in Rochester, New York. Mayor Walker of New York City announced FDR’s nomination to the crowded convention. He lauded the choice of such a “distinguished, honorable American” assuring the crowd that Roosevelt would “maintain the same high degree of efficiency, the same genius, in fact, in government, the same sterling honesty that has characterized the present Governor of this State.”[7] At 1:10 P.M. that afternoon, Roosevelt sent a message to the convention acknowledging his intent to accept the nomination.[8] The nomination of Roosevelt inspired Democratic party leaders.[9] Even the heavily Republican press was pleased with the nomination. Two New York papers, The Sunand The New York Telegram, which had both supported Herbert Hoover in the national election, immediately came out in support of Roosevelt.

GETTING A “RUNNING” START

At once, Roosevelt set himself to the task before him. He plunged into the campaign with the same force of determination with which he had initially refused, though his past reluctance haunted his initial steps. As Kiewe explains, “the campaign ahead was largely defined by Roosevelt’s refusal to run due to the health issue.”[10] The disease that had paralyzed him was once again a hurdle to his ambitions. The New York Herald Tribune threw the first stone on October 3, one day after Roosevelt’s nomination. It complained that his nomination was “unfair to the people of the State who, under other conditions, would welcome Mr. Roosevelt’s candidacy for any office.”[11] Smith backed up his candidate by returning fire through the New York Times:

‘The real fact is this,’ the Governor said. ‘Franklin Roosevelt today is mentally as good as he ever was in his life. Physically he is as good as he ever was in his life….a Governor does not have to be an acrobat. We do not elect him for his ability to do a double back flip or a handspring. The work of the governorship is brain work. Ninety-five per cent of it is accomplished sitting at a desk. There is no doubt about his ability to do it.’[12]

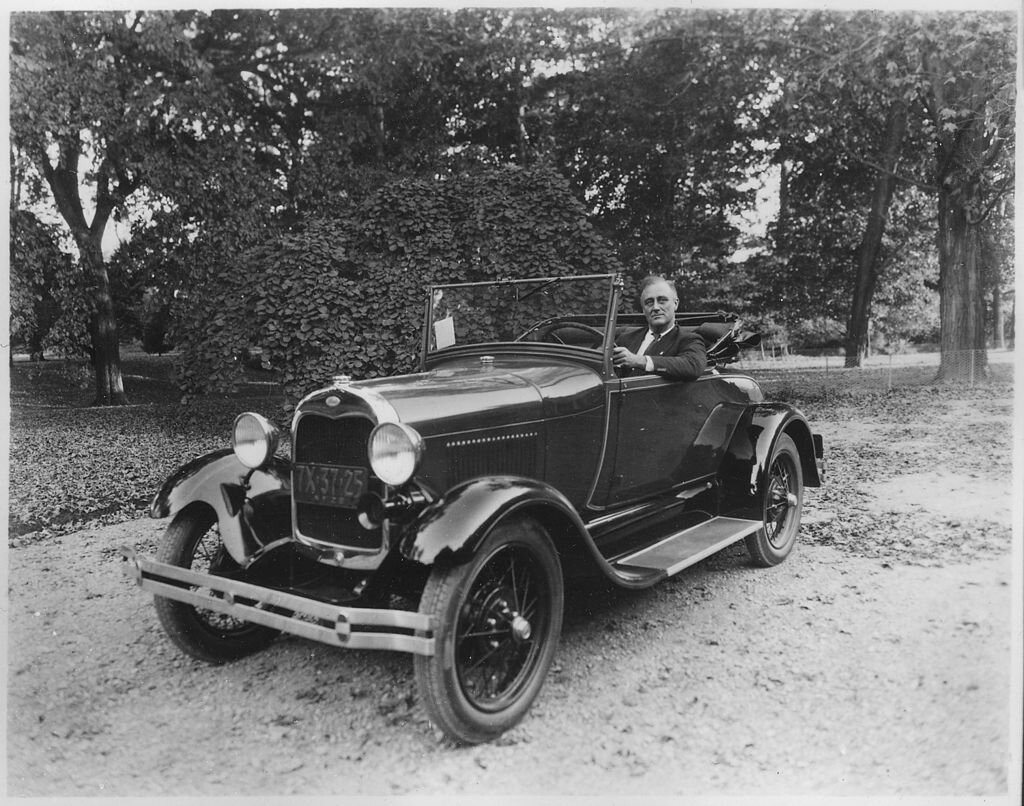

Despite Smith’s vigorous advocacy, Roosevelt would still have to prove to the electorate the truth of those assertions. The key to putting the questions regarding his disability to rest was to cultivate the image of an active and mobile campaigner.[13] He further defused the health question by making light of his disability. In an interview with the New York Herald Tribune, Roosevelt stated that “most people who are nominated for the Governorship have to run, but obviously I am not in any condition to run, and therefore I am counting on my friends all over the state to make it possible for me to walk in.”[14]

Even before returning to New York, FDR had begun planning his campaign. In a telegraph to some of his political allies in the City, Roosevelt indicated that he would run an aggressive campaign for himself as well as other Democratic candidates at the State and national level.[15] Instead of confining his race to the Democrat-controlled cities, plans were put into place to carry the campaign “into the ‘enemy’s country.’”[16] These were the rural districts where Democratic voters had been rare in past elections.[17]

Roosevelt arrived in New York City six days after accepting the nomination via telegraph. He used his travel as an opportunity to campaign for Smith. In one speech on October 6, in Cleveland, Roosevelt revealed some of his up-coming platform for the New York race. Following a denunciation of religious bigotry, Roosevelt stated that he accepted the nomination because he was “so anxious to see Governor Smith’s policies continued that he was willing to make the effort.”[18] He also stated his belief that prohibition was a “cloak for something else” but in his view, the tactic’s effect was receding.[19]

Campaign team

His first stop in New York was Hyde Park where he was greeted by “200 of his neighbors in an impromptu celebration.”[20] On October 8th, FDR met with the candidate for Lieutenant Governor, Colonel Herbert Lehman, and other party leaders at the campaign headquarters in the Biltmore Hotel. The next day, Roosevelt met with Smith to finalize his campaign plans. Among the strategies adopted was the creation of a Citizens’ Campaign Committee designed to register voters and encourage people to go to the polls in November. When Smith last ran for Governor, the Democrats had instituted a similar Committee with success. This time, James Farley and the Chairman of the Democratic Committee, William Bray, were responsible for the up-State campaign, while the infamous Tammany Hall handled New York City and the boroughs.

Apart from Howe and Farley, there were several other indispensable figures in Roosevelt’s campaign. The Bronx Democratic Boss, Edward J. Flynn, was among the first to join Roosevelt’s team. Flynn had been active in Smith’s presidential election but, because of New York’s importance in the national election, he detached himself from the Smith campaign to aid Roosevelt and secure the State’s desperately needed electoral votes. Raymond A. Moley, a professor at Columbia University was summoned to aid the campaign as speech draftsman and as a consultant on issues of crime prevention and criminal justice.[21]

Then there was William H. Woodin. A life-long Republican and the President of the American Car and Foundry Corporation, Woodin had endorsed the Smith campaign in July. He personally contributed $25,000 to the Democratic national campaign fund. Woodin was enlisted as Roosevelt’s “financial dictator.”[22] Henry Morgenthau, Jr. was personally recruited to direct the campaign’s agricultural platform. One of the most important aids brought into was Samuel I. Rosenman who joined after Roosevelt requested an advisor that could supplement his deficiencies concerning the legislative history of the parties in New York.[23]

After conferring with Smith and his team at the Democratic campaign headquarters in the Biltmore, Roosevelt made his first formal interview with the press concerning the gubernatorial race. There, he announced that he did not favor re-enacting the Mullan-Gage State Prohibition Enforcement act. He further added that while traveling throughout the country he had found the Prohibition acts of other States no more effective than those of New York, which relied exclusively on Federal laws.[24] When asked if, as Governor, he would veto a Legislative bill for the enforcement of Prohibition, he replied in the affirmative.[25] He closed his remarks by promising to run an active campaign “with a lot of handshaking and close contact with the voters.”[26]

Campaign starts

By Friday, October 12, the campaign itinerary was released. It listed Roosevelt speaking at nineteen events over nineteen days beginning on the 17th in Binghamton. His final speech would be made on the last night of the election, November 5, in Poughkeepsie at a neighborhood rally.[27] The campaign was officially kicked off when Roosevelt officially accepted the nomination at the National Democratic Club on the 16th. He opened his speech saying, “I accept the nomination for Governor because I am a disciple in a great cause.”[28] The cause he was referring to was the continuation of Governor Smith’s reforms. Continuing, consolidating and making permanent these reforms was the first great issue of the campaign. The second great issue, Roosevelt declared, was whether New York would “undertake new improvements” in government to “keep pace with changing times.”[29]

“Progress means change,” he said, and there were four areas he had in mind. [30] The first was the passage of law mandating the public retention of State-owned water-power resources. Second, he called for a reform of the Judicial System. He asserted that the judiciary “failed to keep pace with the advancement[s] of a practical age.”[31] The final two points focused on New York’s rural districts. He believed that measures were needed to improve the economic conditions of agricultural communities. Finally, he called for governmental reorganization policies at the State level to extend to county and town administrations as well.[32]

With these points Roosevelt launched his campaign. His opponent for the governorship, Albert Ottinger, had already accepted his party’s nomination and begun campaigning. During his acceptance speech, Ottinger indicated his stance on the opposite side of the water-power issue. The Republican Party in New York had long stood against the policy advocated by Roosevelt. Ottinger, in lockstep with his party, was a consistent advocate of private waterpower. If elected, he promised to create a commission of experts to investigate the subject and recommend policy.[33]

Now, read part 3 in the series on what happened during the short 1928 New York Gubernatorial campaign here.

What do you think of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s decision to accept the nomination in 1928? Let us know below.

[1] Davis, FDR: The Beckoning of Destiny 1882-1928, 838.

[2] Ibid., 839-840.

[3] Ibid., 848.

[4] On October 1, Roosevelt had deliberately planned to spend “a long afternoon of picnicking at the Knob, miles from the nearest phone, planning to return to his phoneless cottage barley in time to dress for the political speech he was to make that evening in Manchester, ten miles from Warm Springs.” Thus, he had hoped to “double lock the door of unwanted opportunity.” However, Eleanor knew, as did the Smith, that Roosevelt would not refuse a “person-to-person” phone call from his wife. With this backdrop, Eleanor knew that her assent to Smith’s plea was “no neutral, noncommittal gesture.” Rather, she knew that it would be interpreted by her husband as a silent conclusion that he should accept the nomination. Ibid., 846, 848.

[5] Ibid., 851.

[6] Gunther, 253.

[7] Special to The New York Times, (Oct 03, 1928), “Roosevelt Lauded by Mayor Walker,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[8] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 3, 1928), “Roosevelt Yields to Smith and Heads State Ticket; Choice Cheers Democrats,” New York Times (1923-Current file), 2.

[9] “F.D. Roosevelt Drive Will Start at Once; To Centre Up-State,” (Oct 04, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File, 1.

[10] Kiewe, 158.

[11] Goldberg, 108.

[12] From a Staff Correspondent of The New York Times, (Oct 03, 1928), “Choice of Roosevelt Elates Gov. Smith,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1-2.

[13] Kiewe, 159.

[14] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1928-1932, 31.

[15] “F.D. Roosevelt Drive Will Start at Once,” 2.

[16] Ibid., 1.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Special to The New York Times, (1928, Oct 07), “Bigotry is Receding, Says F.D. Roosevelt,” New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “F.D. Roosevelt Back; Sees Leaders Today,” (Oct 08, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[21] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1928-1932, 33.

[22] “Roosevelt Confers with Smith to Map Campaign in State,” (Oct 10, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[23] Davis, FDR: The New York Years 1928-1932, 35.

[24] “Roosevelt Opposes Any Move to Revive New York Dry Law,” (Oct 09, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[25] Ibid

[26] Ibid., 2.

[27] “Roosevelt to Make Wide Tour of State,” (Oct 13, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.

[28] Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The Candidate Accepts the Nomination for the Governorship, October 16, 1928,” The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Vol. 1, The Genesis of the New Deal 1928-1932, (New York, NY: Random House, 1938), 13.

[29] Ibid., 16.

[30] Ibid., 14.

[31] Ibid., 15.

[32] Ibid., 16.

[33] “Roosevelt Demands State Keep Power,” (Oct 17, 1928), New York Times (1923-Current File), 1.