By the latter half of the 17th century, the rule of Spain in the New World was reaching 200 years. Times were changing, both in the New World and in Europe, and the leaders of Spain knew it. Their problem was what to do about it. Spain had never had a coherent policy in its imperial rule. Since 1492, Spain was seemingly constantly at war, with an endless series of crises thrown into the mix. Solutions had to be found for the here and now, the future would take care of itself.

Erick Redington continues his look at the independence of Spanish America by looking at Venezuelan military leader and revolutionary Francisco de Miranda. Here he looks at Francisco de Miranda’s travels across America and Europe, including his time in revolutionary France.

If you missed them, Erick’s article on the four viceroyalties is here, and Francisco de Miranda’s early life is here.

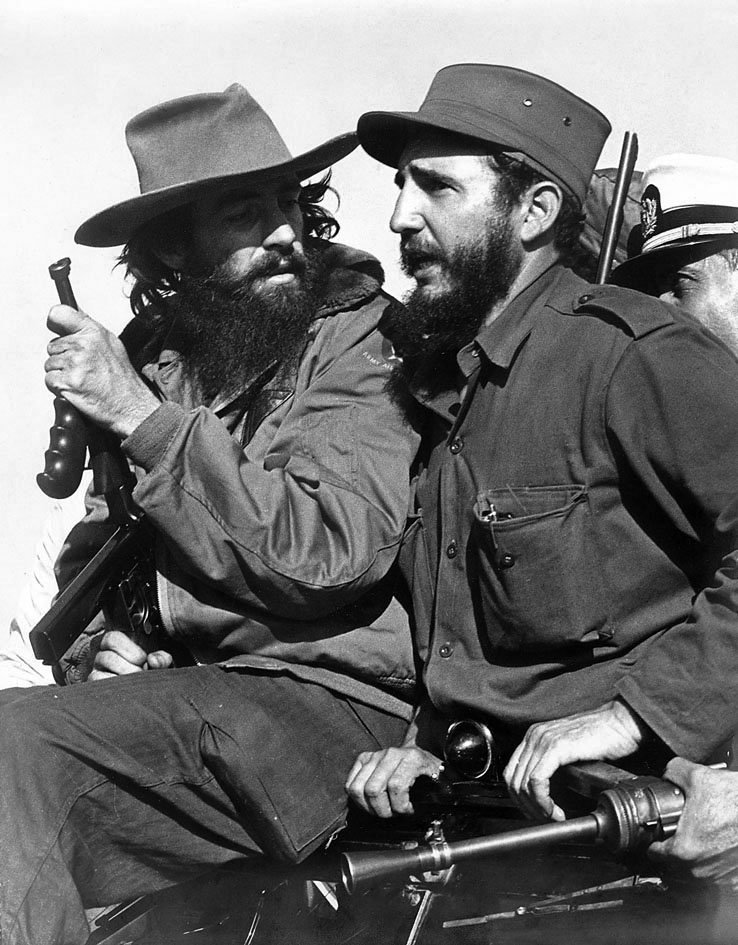

A painting of a young Francisco de Miranda. By Georges Rouget.

Having played a small part in the triumph of the American colonies in their revolution, Miranda wanted to see the society that the Americans were building. It was a natural choice for him. He already seemed to be developing his ideas for the independence of the Western Hemisphere from Europe. A society built upon liberal, enlightenment principles fit into his worldview. Being a highly literate man, Miranda would keep a diary during his travels. This record of his impressions and observations of the early United States is invaluable to any researcher and is one of Miranda’s best historical legacies.

On June 10, 1783, Miranda landed at New Berne, North Carolina. He would travel throughout the United States, seeking to meet not only the biggest players in the revolutionary saga but also the common folk as well. He was impressed that the lower-class whites and the wealthy would mix at common events (he did not mention what the views of the slaves at the events were). From the south, Miranda would journey north to visit the American capital Philadelphia. While in the city, he would insist on staying at the Indian Queen Inn, the same inn where Jefferson supposedly wrote the Declaration of Independence.

Armed with letters of introduction from those he met in the south, Miranda would put his natural charm and wit to work to ingratiate himself into Philadelphia high society. Since word of his status with the Spanish government had not caught up with him yet, he was wined and dined by members of the American government as well as foreign ambassadors and prominent citizens looking for Spanish contacts. Encountering George Washington, Miranda would say that he could not make a firm judgment on the man, due to his “taciturn” disposition. Lafayette, Miranda would find to be overrated. Leaving Philadelphia, Miranda would go to New York and meet two people who would influence his later life: Thomas Paine and Alexander Hamilton. Paine will become important later. Hamilton and Miranda were very much alike. Both men were bursting with energy and ideas. Both men believed that they had a destiny to lead their respective peoples. Both were highly intelligent and literate. Until Hamilton’s death, Miranda would continue to think of Hamilton as a friend.

After touring upstate New York and New England, Miranda’s past was beginning to catch up to him. Word from Spain had begun to filter into the United States. Instead of being an innocent victim of slander that Miranda had passed himself off as, he was in fact a deserter who was sentenced to lose his commission, pay a fine, and face exile. Miranda could no longer pass himself off as a lieutenant colonel of the Spanish Army. This change of status proved to be liberating in a way. When Miranda arrived in Boston, he used his letters of introduction to meet General Henry Knox, the future first Secretary of War under the Constitution. Miranda, Knox, Samuel Adams, and other men of the Boston merchant community would become intimate friends and form a discussion group. Over brandy, Miranda would spellbind these men with his ideas for the liberation of South America from the Spanish. Once Miranda saw all he thought he could see, as well as met all who were worth meeting, it was time to leave. While Miranda wanted to see the great experiment in action, he knew that at the present time, the United States was utterly incapable of furthering his plans for an independent South America. For this, he had to go to Europe.

Miranda Tours Europe

The Grand Tour was a trip around Europe that many upper-class people took as something like a right of passage after their schooling had been completed. It gave the young person a sense of worldliness and provided exposure to the cosmopolitan nature of 18th and 19th-century European upper-class society. Miranda, being a colonial, had not had the chance to go on the Grand Tour. He would rectify his missed chance. After reaching London, he would set out for the Netherlands and see the Continent.

As a man with command of many languages and being extremely well read, Miranda was able to ingratiate himself with the high society of each country he went to. His good looks and high wit were also helpful. He seemingly met everyone from Frederick the Great to Catherine the Great. He toured seemingly every city and historical location from Stockholm to Constantinople. Composers, philosophers, writers, and princes were all enthralled by him. He even allegedly had an affair with Catherine the Great, although this was never confirmed.

These contacts were not merely social for Miranda. It was a learning experience, yes, but he was also searching for support for his cause, the independence of Spanish America. Needing money, he would take financial support from them, then commonly called “patronage.” When he would inevitably (in his mind) strike for that independence, he wanted a network of supporters in Europe with their hands on the levers of power and money to give him their support when the time came. He was not simply playing the part of the international playboy gallivanting across the courts of Europe. There was a political dimension to this as well.

During his travels, Miranda would have to keep one eye always open. The Spanish government was still plotting to have him arrested. Through the Spanish intelligence network in Europe run through their national embassies and consulates, the Spanish would constantly attempt to arrest Miranda and bring him back to Spain. They knew what Miranda was doing, undermining their rule in the New World. In the end, the Spanish would fail to capture him due to a series of fortunate escapes as well as the influence of powerful friends. To protect Miranda, Catherine the Great would even make him a member of the Russian diplomatic service, thereby extending him diplomatic immunity.

For five years, Miranda would travel Europe. His travels would leave an indelible mark on those he met. In 1789, he traveled to France. Seeing the country, he despised what he saw as the backwardness of the peasantry. He wrote about visiting Versailles and feeling humiliated as he was forced to kneel upon seeing King Louis XVI. Miranda was not a fan of the French governmental system, and seeing it firsthand only made him despise it even more. He would leave France and return to London to begin lobbying the British government to support him.

Revolutionary Times

Miranda had a great deal of admiration for the British people and the balanced constitution of Great Britain. Although Miranda would remain a committed republican throughout his life, he would always recognize the inherent genius of the British governing system. Much of his admiration of the system itself would be tempered by seeing that system operate up close in his dealings with British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger.

Miranda would bombard Pitt with plan after plan and scheme after scheme to liberate South America from Spanish rule. All he would need, he would tell Pitt, was money…and men…and arms…and ships, etc. Miranda was the ideas man, the brains of the operation. All of the material support would have to come from elsewhere, and where better than the richest government on the planet, the British. Pitt would always keep Miranda close enough to use him. Occasionally throwing out hope to Miranda would keep him around just in case war with Spain would break out and he might in some way be useful. For over a year, Miranda would act out the same song and dance with the British government until he could bear it no longer. He decided he would go back to France.

Why go back to France, a country Miranda held in little esteem? Because, during his time in London, the French Revolution had broken out. The people had limited the powers of the King and were overthrowing society through the National Convention. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, authored by his friend Thomas Paine, captivated him. Here was a revolution, freeing the people and ushering in the glorious millennium of human freedom.

Arriving in 1791, Miranda would find France at war with almost all of its neighbors. The powers of Europe found the prospect of a revolutionary and trending radical republican France upending hundreds of years of tradition, as well as the balance of power on the continent, terrifying. The revolutionaries needed anyone with military experience to help secure the revolution from foreign powers whose stated goal was to overthrow the Convention and restore the powers of the king. Miranda had military experience and was made a general and ordered to take command of troops as part of the Army of the North.

With the Allies coming over the Rhine and looking to take Paris, the French needed victory. The Battle of Valmy, while being little more than an artillery duel, led to an Allied retreat. This victory was blown up in republican propaganda and was the victory that saved the Revolution. All the men involved became heroes and were declared military geniuses, and this included Miranda.

With his military reputation sky-high, Miranda was given command of a wing of the Army of the North. He was ordered by the commander, General Dumouriez, to invade the Austrian Netherlands (roughly modern Belgium) and the Netherlands. He would take Antwerp and exact a £300,000 “loan” on the city. With Dumouriez in Paris, Miranda was ordered to occupy Maastricht by the National Convention. An Allied counterattack would lead to a rout on the part of Miranda’s army. Dumouriez would return to try to salvage the situation, but it was beyond saving. Miranda had suffered a humiliating defeat. Dumouriez, however, believed the situation could be turned around. He would reorganize his forces and counterattack. At the Battle of Neerwinden, Miranda was in command of the left wing of the army. He was ordered by Dumouriez to attack the Austrian right wing. The Austrian commander, the Prince of Coburg, reinforced his position and the battle went back and forth for several hours. When the cavalry of Archduke Charles was sent in to press the attacks home, Miranda’s command was broken, and the men began to flee. Despite all of his best efforts, Miranda was unable to rally his men. Dumouriez, learning of the shattering of his left wing, ordered the army to retreat.

The Radicals Turn on Miranda

For Miranda, the defeat at Neerwinden was very ill-timed. The Revolution was taking a dark turn. The siege mentality of the National Convention was turning into political paranoia as the different factions were turning on each other. The faction he was associated with, the Girondins, was in decline, while their rivals, the Jacobins, were ascendant. In April 1793, Miranda was arrested. His old commander, Dumouriez, recognizing the cut-throat nature of revolutionary politics, denounced Miranda and stated that the blame for the defeat in the north could be laid almost entirely in Miranda’s lap. Miranda was accused of criminal incompetence and cowardice in the face of the enemy.

Then the situation became even more confused. Dumouriez, seeing the way the Revolution was turning, decided to try to overthrow the Convention and restore a previously discarded constitution. Counting on the loyalty of his troops to himself personally, Dumouriez negotiated with the Austrians to stop their advance in order to free up the Army of the North to march on Paris and suppress the Convention. As it turned out, the troops were not loyal to Dumouriez personally, and he was forced to flee across enemy lines and defect to the Coalition. Back in Paris, the first reaction amongst the radicals was that of course, Miranda had supported his old commander Dumouriez in his treason. This flew in the face of all logic since it was Dumouriez who was trying to destroy Miranda’s reputation. Despite this, the paranoia of the Jacobins, and their leader Robespierre, knew no bounds. Miranda would be brought to trial for both sabotaging Dumouriez’s chances at victory as well as allegedly supporting the same man’s treason.

On April 8, 1793, Miranda was interrogated by the Convention’s War Committee. The questioning of Miranda and his fitness for command as well as his actions gave him the opportunity to address the committee and state his case. All of the learning, literary training, and military studies that Miranda had focused on his entire life led to this moment. Against all odds, he was able to defend himself so well before the War Committee that he was able to escape the guillotine. He showed the logic of his actions, proved the accusations of cowardice to be false, and attacked the judgment of Dumouriez. He even commented on Dumouriez’s negative opinions of the members of the Convention, just for good measure.

In May 1793, Miranda appeared before a Revolutionary Criminal Tribunal, which again investigated the charges against him. Witness after witness would appear before the tribunal to support Miranda. Even Thomas Paine would take the stand in Miranda’s defense. The defense attorney, Chaveau-Lagarde, would point out to the jury all that Miranda had sacrificed for the freedom of the French people. He showed that Miranda was a man with an international reputation for integrity and was known as a lover of mankind and a freedom fighter. The letters of introduction from men such as George Washington, Joseph Priestly, and Benjamin Franklin were introduced to prove Miranda’s devotion to republicanism. Although the process would take too long in the judgment of Miranda, he was acquitted on all charges and released. The jury had unanimously returned a verdict of not guilty.

In Revolutionary France, no one was truly safe. In July 1793, the most radical leaders of the revolution began to consolidate their power in the lead-up to the Great Terror. On July 5, Miranda was arrested again, this time at the order of the Committee of Public Safety. The Jacobins were determined to destroy their Girondin opponents, and Miranda was one of the most prominent. This time, imprisonment would not be the same. Whereas before, Miranda had been incarcerated for only a few weeks, this time, he would sit in prison for much longer. Even after the fall of the Committee of Public Safety and the defeat of the Jacobins, Miranda was still not released. Only after a year and a half, in January 1795, would Miranda finally be let out of his dungeon.

During his time in prison, Miranda had begun to lose faith in the Revolution. He would begin to write and speak to his contacts about how the Revolution had lost its initial ideals. He opposed “spreading the revolution” through military conquest and expressed his skepticism of the French government. He would write a pamphlet calling for the reformation of government to create more checks and balances to prevent dictatorship and tyranny. Given Miranda’s international connections and reputation, it could not escape the French government that he had to be taken seriously. On October 21, 1795, the Convention ordered Miranda to be arrested yet again. Although this order would be rescinded, the French government was growing very tired of Miranda.

Returning to His Roots

In 1797, the French government was prepared to deport Miranda to Guiana. He knew his time in France was up. Before he would leave, however, he would take the opportunity that being around other revolutionary exiles afforded and held what was later called the “Paris Convention.” This meeting between Miranda, José del Pozo y Sucre, and Manuel de Salas drafted an Act of Paris which set out points that would guide the South American independence movements. Independence and friendship with Great Britain and the United States, repayment to Britain for services rendered to the revolution, commercial concessions to Britain, and recognition of Miranda’s leading role in the military aspect of the revolution. These men knew that the South Americans would have a hard time freeing themselves. They needed British support.

With the Act of Paris complete, Miranda prepared to leave France. He came to the country and was filled with disgust for the absolutist French. Seeing the Revolution, Miranda became a convert to the French cause and put his life on the line to defend it. The repayment he received was accusations and imprisonment. Coming full circle, Miranda would leave France bitter against both the country and its people. He had always favored British and American models, but his experiences had only reinforced his early views.

In January 1798, Miranda would leave France and arrive in Britain. Now, at 47 years old, having seen much of the Western world, met many of its leading lights, and had his star rise, fall, rise, fall, and rise again, Miranda would now turn back to the primary thought driving his life, the freedom of Spanish America from colonial rule. No more diversions, it would now be all-encompassing.

What do you think of Francisco de Miranda’s time in America and Europe? Let us know below.

Now, read about Francisco Solano Lopez, the Paraguayan president who brought his country to military catastrophe in the War of the Triple Alliance here.