In 1935 Fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini’s rule, invaded Abyssinia, one of the few independent countries in Africa at the time. The war split opinion in Europe, and caused particular issues for Britain and France as they hoped to ally with Italy against Nazi Germany’s plans. Should they strongly intervene against Italy, or offer a more limited response? Stephen Prout explains.

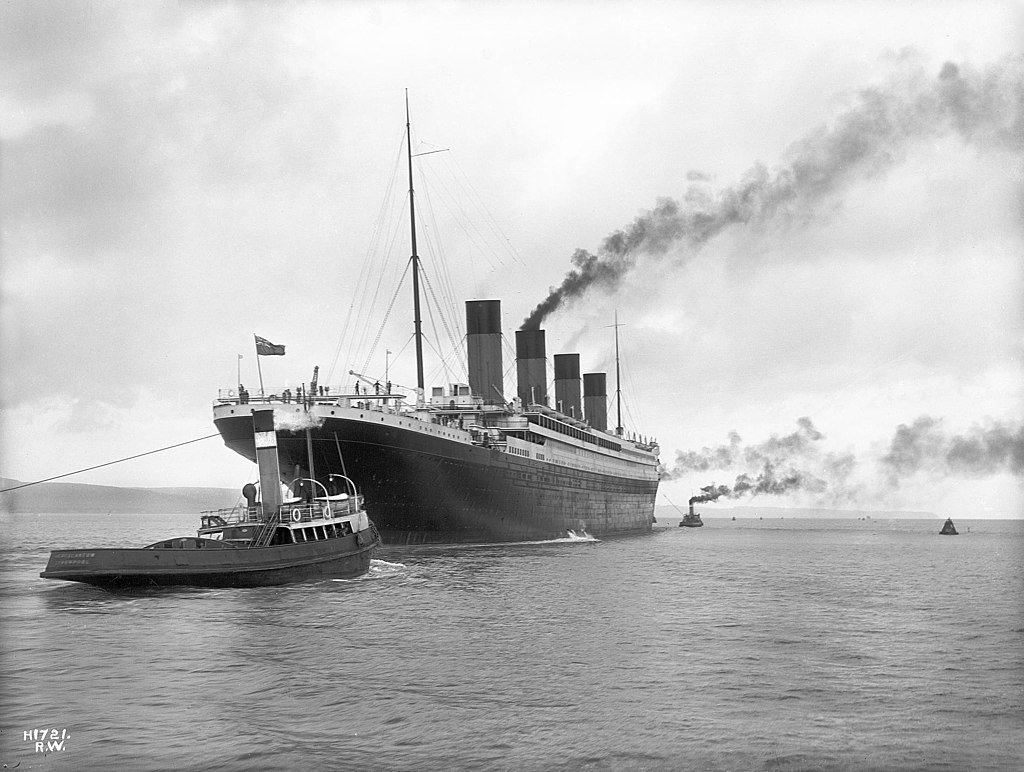

Italian troops advancing on Addis Ababa during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935-37).

Introduction

In 1935 Italy invaded Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia). Italy was then under the control of a fascist regime ruled by Benito Mussolini and part of his grandiose plans was to expand Italy’s modest empire. In the immediate years after the First World War’s end there was deep dissatisfaction with the terms of the Paris Peace conference, Vittorio Orlando and Sonnino his Foreign Ministers departed early betrayed by her Western allies. In the 1915 Treaty of London Italy’s former allies, Britain, France, and Russia, promised her territory in the Balkans and North Africa in return for her participation in the war on the Allied side - but these promises were broken and she left empty handed. Mussolini came to power in 1921. His aspiration was clear - it was to make Italy great, respected and feared. Part of that plan was the expansion of the Italian Empire.

Abyssinia was Italy’s first major territorial gain and in October 1935 forces of the Italian Army conquered the country isnless than a year. The new League of nations would be outraged and on the surface Britain and France would be disapproving. Although the conflict was on a different continent thousands miles away it had grave significance for European affairs. The outcome would place an isolated Italy in the Nazi Camp and once again divide Europe into two opposing camps.

Abyssinia and its relations with Europe

The imperial powers had always been present and hovering in the background since the late nineteenth century ready to meddle in Abyssinian affairs. Italy had long carried an irreconcilable sense of national humiliation from her defeat by Abyssinian forces in 1896 at Adwa. She had not had the opportunity to repair her international standing in the same way Britain did when the Zulu army overcame British forces at Isandlwana in the 1880s. This had always been a blight to Italy’s new national pride.

As far as other European powers were concerned, in 1906 Italy along with Britain and France formed a Tripartite Pact in which spheres of influence in Abyssinia were established amongst the three powers, and they were ready to enact and occupy in the event of the country’s collapse following a period of turmoil.

Abyssinia was one of two independent countries in Africa in the 1930s (the other was Liberia). That set them apart from the rest of the colonized continent (slight exceptions were South Africa and Egypt who had semi-autonomous roles as either veiled protectorates or Dominion status). Africa was still very much under European domination, mainly Britain and France. Italy was seeking expansion in North Africa, the Balkans and the Mediterranean. Abyssinia offered that sole opportunity as far as Africa was concerned. Trying to seize British or French territory was militarily out of the question for her.

When compared to European standards Abyssinia was very much behind economically, socially, and politically. Abyssinia entered the twentieth century with many of its medieval ways and customs intact. It operated a slave trade this far into the twentieth century and it did not end until after the Second World War. The education system excluded much of the population and the army was largely equipped with traditional weaponry. Conversely there was evidence of a nascent modernization as she had access to modest trade with the USA, Germany, Britain, and Italy at the turn of the century. For example in 1906 its exports to the USA amounted to 3 million dollars ($106 million in today’s money). Internally the education system was also progressing as a government edict made education compulsory for all males and it was no longer restricted to religious instruction.

For Italy there was the unresolved matter of her military defeat in 1896 and the promise to expand the Italian Empire to make good the broken promises of the 1915 Treaty of London. The pretext Italy used to justify the war was a retaliation to border violations after growing tensions supported with a spurious claim to abolish the slave trade that continued in Abyssinia. Mussolini had made it clear that he wanted to build a new Roman Empire and make Italy respected and feared. Abyssinia was his opportunity and he justified the action by believing that he was acting no differently to Britain and France in Africa. However, his mistake was not realizing that the time of empires and colonies had no place in the mid-twentieth century. Italy was fifty years too late for an African scramble.

The Dilemma for Europe

As far as the British public was concerned, on the surface this was a moral battle. An underdog nation was fighting for its existence against a more powerful aggressor. This hypocrisy seemed to largely ignore the fact that Britain still had a firm grip of its empire and was in some areas supressing with force independence movements. The resolve that was expressed however was clear and it was any action short of war, with no intention or plan for any alternative. In diplomatic circles in Europe the perspective was very different indeed. The events in Abyssinia from the Italian invasion were more of a side show but how could a developing country some eight thousand kilometres from Europe be a concern to the Western Powers of Europe and indeed Germany?

In truth the British and French were not concerned over Abyssinia. It was public opinion and the state of the League of Nations that forced the appearance of urgency from Britain and France. Underneath all this Italy was an ally despite its Fascist nature - and more importantly a member of the recently formed alliance that became known as the Stresa Front Alliance with France and Britain that had the aim of maintaining peace and stability in Europe and containing revisionist Germany. It was important that she was not irked or isolated by actions that Britain or France may be compelled to take on direction or pressure from the League of Nations.

Britain only had her own interests in mind and that was security in Western stability and her own colonies. The Permanent Under Secretary of State for the Colonies, John Maffey, quickly assured the Government that none of the nation’s British interests were at risk after the Italian invasion. At home not all British politicians shared the public outrage. Within the Conservative Party, Leo Amery expressed his support for the Italian actions. Churchill remained quiet on the matter. The widely held belief of Amery is that he was an anti-appeaser due his famous speech that he would make later in 1940 demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. In fact, quite the reverse was true. Amery voiced support for the Japanese invasion of Manchuria as well as for Italy’s actions in Africa. Amery argued in the case of the former that Japan had a “strong case for her invasion of Manchuria” and that Britain and France should have ceded Abyssinian territory much earlier to Italy and eschew League intervention. More specifically, in 1936 he stated that the Italian intervention would give a “merciful deliverance to be released from Abyssinian control”.

Britain was also concerned with her appearance before the League of Nations and had to balance her own interests with her obligations as a leading member. The Abyssinian crisis showed how impotent the League could be in the face of aggression from a permanent member and also when combined with conflicting interests and agendas of the members. Some diplomats were quite willing to circumvent the League in such cases as Lord Curzon during Italy’s actions in Corfu. In the background there was the concern that the presence of an independent nation on the borders of Europe’s colonies could also spread nationalistic ideas. This was especially a worry for Britain who had lost Egypt, Ireland, and Iraq already, while India was showing noisy displays of dissent. Therefore the Italian invasion of Abyssinia would not inconvenience her nor the French too much. Ever since In the Tripartite Treaty of 1906, the three were all prepared to occupy this independent nation if their own interests were threatened or if the situation in the country did not favor them.

For Britain and France Italy was more valuable in keeping on side within the 1935 Stresa front. Italian membership and military support were vital and essential if Germany was to be contained. The Western democracies were making overtures to Mussolini to avoid his isolation while applying very modest and meek sanctions to keep up appearances in the League. Abyssinia would be a small price to pay for their own security and interests, but ultimately the 1935 Stresa Front would crumble.

The Outcome

The outcome of the war was a victory for Italy. Within a year of the conflict ending the new Prime Minister of Great Britain Neville Chamberlain was already exchanging friendly correspondence with Mussolini and in 1937 was ready to acquiesce to Mussolini’s requests for recognition of Italy’s complete annexation of Abyssinia. Spheres of influence that were established in the Tripartite Act of 1906 were forgone, and the Western Powers even passed up the chance to fight for territory in Abyssinia. This displayed not so publicly how quickly the Western Powers could move on but how unimportant the sovereignty of Abyssinia was to them. Britain and France were colonial powers, and the disappearance of a sovereign nation would help to extinguish ideas of independence reaching their own colonies.

Britain and France could potentially have saved some of Abyssinia if they chose to by invoking the 1935 Stresa Front. By occupying their self-proclaimed spheres, they could have denied much of the country to Italian forces. This would have been a grander gesture than the mild sanctions applied. It only strengthened the point that the fate of Abyssinia was just not important enough.

Like all wars it had atrocities and more has been focused on the use of poison gas by Italy. Equally, Abyssinian combatants also acted outside of the conditions of the Geneva convention. The International Red Cross reported the castration of Italian prisoners of war by Abyssinian troops. Furthermore, it should be also noted that while under Italian occupation the slave trade was curtailed and outlawed, something which showed no signs of being arrested under the country’s old rulers. During Italian rule two laws were issued in October 1935 and in April 1936 which abolished slavery and freed 420,000 Ethiopian slaves. While not condoning Fascist actions the campaign was not as one sided as some accounts suggest. As far as the rest of the world was concerned the indifference to the fate of Abyssinia fate was shared as only six nations failed to recognise the Italian fait accompli.

The Abyssinians endured ten years of Italian occupation. Europe had now been forced into two camps with Italy now firmly on the side of the totalitarian powers rather than a country that would contain a growing and powerful Germany. Italian actions in Abyssinia along with Japanese intervention in Manchuria were portents. Italy would soon join Germany in intervening in Spain before participating against her former allies in the Second World War. Was it inevitable or was it a diplomatic tragedy?

What do you think of the Abyssinian Affair? Let us know below.

Now, if you enjoy the site and want to help us out a little, click here.

Sources

Encyclopaedia of Antislavery and Abolition [Two Volumes] -Greenwood Press, 2006 - Peter P. Hinks, John R. McKivigan, R. Owen Williams

Mussolini- A New Life – N Farrell – 2003 – Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

AJP Taylor – English History 1914 – 1945

Europe of The Dictators

Report of War Crimes and Atrocities Abyssinia – International Red Cross

Leo Amery’s Imperial Attitude to Appeasement in the 1930’s – Richard S Grayson – University of London 2006