Here Kate Tyte gives us a fascinating overview of Mesmerism, a popular hypnotic process that united all classes and many people believed in through the 18th and 19th centuries.

“There is only one illness,” pronounced Franz Anton Mesmer, “and only one cure.” This cure was animal magnetism, a practice that united eighteenth century society in debate. From royalty to peasants, politicians to revolutionaries, scientists to Freemasons: everyone had an opinion on magnetism.

Franz Anton Mesmer was born in Germany in 1734. He studied medicine in Vienna, married a wealthy widow and became a fashionable doctor. Not bad for the son of a game keeper.

In 1774, Mesmer was introduced to patient Francisca Oesterlin. She suffered from ‘constant vomiting, inflammation of the bowels, stoppage of urine, excruciating toothache, earache, melancholy, depression, delirium, fits of frenzy, catalepsy, fainting fits, blindness, breathlessness, and lameness.’ Mesmer tried a novel cure. He gave her a medicine containing iron and applied magnets over her body to create an ‘artificial tide.’ Oesterlin was cured. In fact, she was so well she soon married Mesmer’s step-son. Mesmer now theorized that the whole universe was held together by magnetic fluid, and that disease was caused by blockages in free-flow of this fluid through the body. Animal magnetism was born.

Mesmer developed his cure. He would stare into his patient’s eyes and massage their body, wave a wand at them, or have them put their feet in magnetic water, until they had a ‘crisis’ or a fit and were cured. He was soon hounded out of Vienna as a charlatan and moved to Paris. Once again the medical and scientific authorities were skeptical, but the public loved magnetism so much he had to introduce group cures. His patients would hold onto a tub of magnetized water, a magnetized tree, or simply hold hands.

The authorities felt threatened by Mesmer’s miracle cures and were determined to stamp out animal magnetism. In 1784 the King appointed a Royal Commission of eminent scientists, led by Benjamin Franklin, to investigate. It was rather awkward as they were all members of a masonic lodge that was very keen on magnetism. But their scientific self-interest won the day. They reported that ‘magnetic fluid’ was humbug and that Mesmer’s cures were either fake or a product of the imagination. Mesmer was a staunch materialist and strongly denied that his cures were produced by the mind.

The commission finished Mesmer’s career. He left Paris and drifted around Europe. He was later imprisoned in Vienna as a suspected revolutionary, and died in Germany in 1815.

Magnetism lives on!

Meanwhile, animal magnetism continued to march through Europe and remained as popular as ever. This was hardly surprising. In the late eighteenth century all the medical establishment could offer was blood-letting, vomits and purges. Given the choice between a cure that was painful, dangerous and useless, or one that was pleasant, safe and useless, I would pick the latter option every time.

In 1784, the same year as the Royal Commission, Armand Marie Jacques Chastenet, Marquis of Puysegur, took magnetism in a new direction. He discovered he could induce a new state of consciousness, called ‘artificial somnambulism’ or ‘magnetic sleep.’ This sometimes gave patients occult powers such as clairvoyance and extra-sensory perception. Puysegur’s ‘spiritual’ or psychological version of animal magnetism, became known as ‘mesmerism’, and ensured the continued popularity of the practice.

The British

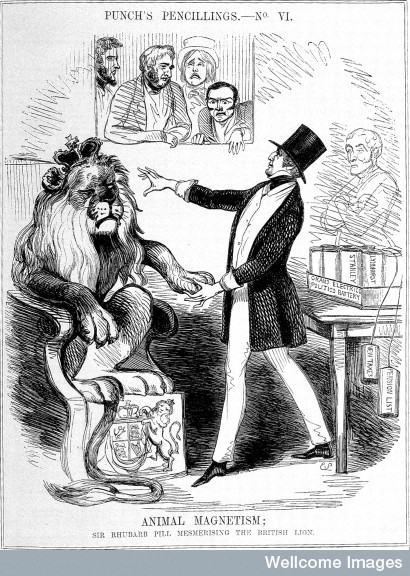

Mesmerism spread to Britain in the 1780s. The establishment was skeptical. They saw mesmerism as unscientific, and worse, un-English. The Frogs and the Krauts might go in for such effeminate mumbo-jumbo, but John Bull was not going to fall for such nonsense. Despite this, the political classes got quite hysterical about it during the revolutionary wars. They worried that the French were using ‘magnetic spies’ to pry into the minds of the British.

Mesmerism was re-born in Britain during the 1830s and 1840s when several popular books on the subject started a craze dubbed ‘mesmeric mania’. The salons of high society delighted in mesmerism and even Charles Dickens had a dabble. Many people think of mesmerism as an eccentric pursuit by the fringes of Victorian society, but for about 20 years it was all-pervasive and inescapable in every aspect of British life.

The working classes were just as fascinated by mesmerism as the wealthy. Mesmeric showmen toured the country giving demonstrations. Mesmerism’s appeal was obvious. It was exciting, mysterious and wonderfully meritocratic. Anyone could mesmerize. There was no need for expensive training or membership of exclusive professional bodies. Mesmerism was used as a cheap form of medicine for the poor and also a way to explore paranormal phenomena, such as clairvoyance. It could also be deliciously subversive. Men who dropped their aitches could mesmerize duchesses, throwing the whole social order into glorious disarray. And some Socialist groups actually promoted mesmerism as part of a radical political agenda.

The medical profession, though, remained vehemently opposed to mesmerism. John Ellitson, senior physician at University College Hospital and respected medical author, was eager to experiment. He found mesmerism helped many of his patients so he began lecturing on it. This caused a mighty row with the hospital authorities and ended his career. The hospital didn’t care whether mesmerism worked or not. They simply felt that it was disreputable and a threat to their status. Thomas Wakley, editor of The Lancet, said that mesmerists ought to be shunned “more than lepers, or the uncleanest of the unclean.” Wakley had no such qualms about the ludicrous pseudo-science of phrenology.

The medical profession even dismissed mesmerism’s use for surgical anesthesia. Hundreds of operations were carried out using mesmeric pain relief in the 1830s and 40s. At one colonial hospital in India, mesmeric anesthesia caused the death-rate to plummet by 50%. The medical establishment simply ignored this evidence and claimed that all the patients had been faking it! Ellitson asked in despair, “How long will you refuse to spare a single wretched patient the pain of your instruments?”

As it turned out, not long. Mesmerism made the infliction of pain surgery seem like an avoidable trauma, rather than a simple fact of life. Mesmerism inspired surgeons to experiment and by the 1850s ether and chloroform were being used widely.

The mesmeric craze died out in the 1850s. Chemical anesthesia rendered it redundant in operations and the public had moved on to a new craze for séances, ouija boards and spiritualism. It took many years for mesmerism, or hypnosis as it was later called, to be taken seriously and recognized as tool with great potential for psychological healing. In the meantime the mesmerism craze was practically written out of history as a silly and embarrassing episode. This was unfair, as mesmerism had in fact spared many patients from pain and suffering.

By Kate Tyte. Kate is an archivist, history writer and blogger. You can follow her on twitter at @KateTyte and find her blog at katetyte.com.

You can also find out more about Mesmerism in Robin Waterfield’s Hidden Depths – The Story of Hypnosis. Available here: Amazon US | Amazon UK