In this article, Kevin K. O’Neill looks at crime in early 19th century London. This was an age before the birth of the police, and in this grimly Dickensian world, crime was rife. Some of the crimes committed were simply shocking.

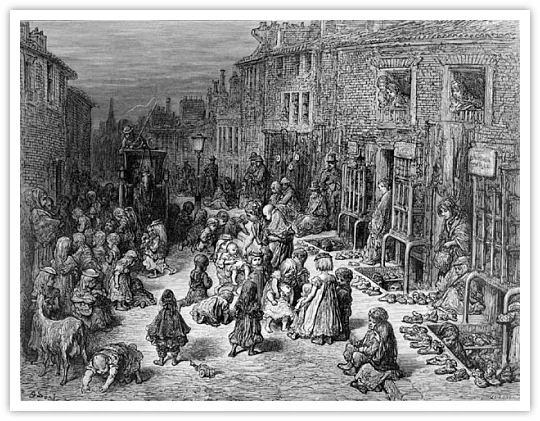

A street scene from 19th century London.

“Napping a Tick”, “Doing Out and Out with a Pop”, and “Teased” were but a few examples of the slang used by the denizens of London’s underworld in the early 1800s for stealing a watch, killing someone with a gun, or being hung. Before the formation of the Metropolitan Police in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel, the original “Bobbie”, London was fertile ground for crime to take root and grow. Sparsely lit by gas in only a few select areas, London was dark, in some areas even by day. With the murk of burnt sea coal hanging over the docks that were busily taking in valuable goods from every corner of the world, all manner of crime was possible, crime that was abetted by this dim anonymity. With a population of about one million inhabitants in the early 19th century, London was sharply divided by class with much of the disenfranchised lower classes active only at night. The only official watchmen, known as “Charlies” because of their creation in 1663 during the reign of Charles the Second, were armed only with a stave, lamp and rattle. Often morally and physically decrepit, they were rarely effective and often the butt of jokes. Indeed, a pastime for the drunk or bored was knocking them over in their watch-boxes.

Social Issues Grow

By the mid-18th century many factors were contributing to the need for a unified police force and social reform. One of the main influences lied in the pervasive effect of cheap gin, or “Blue Ruin”, on the lower classes of England’s populace. In some areas there were unlicensed gin shops, and the crime rate was proportionate to the density of these establishment. Some gin houses, termed “Flash Houses”, were meeting spots for criminal gangs and liaisons between underworld operatives and the greater public, including law enforcement, who would drink and gather information. In 1780, fueled in part by Blue Ruin and economic disparity, peaceful demonstrations against laws emancipating Catholics turned into what history remembers as the Gordon Riots, as part of which there was mob rule during a week long orgy of window shattering and violent assault. Much was said in Parliament after these riots, but little was done.

A scene from a slum in London.

Crime was rampant in early 19th century London, with numerous types of thievery permeating many aspects of life in London. Burglary from houses was so common that elaborate precautions had to be taken before leaving home for any amount of time longer than an hour or two. Every coachman was a guard as trunks could be cut from their vehicles in the blink of an eye. Petty thievery was a threat from many vectors such as the destitute “Mudlarks”, who wallowed in the mud of the River Thames hoping for valuable goods to be dropped from ships by chance or on purpose. Swarms of pickpockets haunted the richer areas of the city. Many of the petty thieves were children as young as ten, but arrests are known of children aged six. Beggars, often living the most pitiable existence, lined many of the same streets.

This all meant that several private law enforcement agencies were formed so that businesses and citizens could protect themselves from loss. Known for their fleetness of foot, the exploits of the Bow Street “Runners”, employees of an organization created to watch and protect property on the docks, were followed by the public with sportsman’s glee as they pursued the more successful thieves before they gained safety in the dark slums or “Rookeries.” The rookeries were notoriously dangerous areas in which nobody or nothing was safe - be it life, limb, or property. Charles Dickens once ventured into several rookeries, including the notorious “Rat’s Castle,” as the St. Giles Rookery was known, but did so only with an escort consisting of the Chief of Scotland Yard, an assistant commissioner, three guards, probably armed, and a squad within whistling distance. Perhaps more worryingly, a bold doctor who entered a rookery commented that he couldn’t even find his patient in his room until he lit a candle, despite the time being near noon.

Resurrection Men

And on to a crime that seems almost unbelievable…

Many of us are familiar with the horror movie theme of stealthy men with slotted lanterns lurking about graveyards with spades in hand in search of a fresh grave. This theme has more basis in fact than most realize as the “Resurrection Men” performed this ghoulish task on most every moonless night to supply the British medical community with fresh cadavers for study and dissection.

The story goes that as a deterrent to crime The Murder Act of 1752 allowed judges to substitute public display of an executed criminal’s body with dissection at the hands of the medical community thus giving the Resurrection Men legal elbow-room. The activities of the doctors and body snatchers were despised by many of the general public though. And mob justice was often dealt out to Resurrection Men caught performing their grim work, while patrols were increased at the upper-class graveyards and the rich bought special coffins to ensure their undisturbed rest peacefully. Finally, the public’s unease at the practice became anger with the Burke and Hare murders of 1828 in Edinburgh.

Burke and Hare, a pair of Irish immigrant laborers turned Resurrection Men, decided to expedite matters by killing sixteen people to be sold to the proxies of an Edinburgh anatomist, a doctor named Knox. The term “burking” traces its origins to the method they used for killing - the use of a pillow to smother victims. Once caught Hare turned the evidence against Burke in court. Ultimately, only Burke was convicted; after Burke’s execution, a hanging attended by thousands, he was publicly dissected in front of students at the University of Edinburgh. Those left outside without tickets demanded to be let in, until finally being led through the operating theater in groups of 50. Never interred, Burke’s remains were doled out for medical study, with pieces of his skin being used for books and calling card cases.

There were other co-defendants in this trial and they suffered similar fates to each other. After release from prison they were hounded by mobs at first identification. All were aided by the authorities to flee in various directions in search of security through anonymity. Never prosecuted due to his insulating layer of agents and Burke’s denial of his involvement in his confession, even Dr. Knox was vilified by the populace who hung and burnt him in effigy. It is notable that Burke asked that Dr. Knox pay five pounds owed to him for his final victim’s body so he could be hung in new clothes. Trying to address both the needs of the medical community and the moral outrage of the people, The Anatomy Act was passed in 1832. This law ended the use of executed murderers for dissection while enabling relatives to have the ability to release bodies of the newly deceased for the good of medical progress. For those who passed without known relatives, legal custodians such as public health authorities and parish councils were allowed the same right.

Now read on to find out about more on crimes in 19th century England, including the original Tom and Jerry, and a famous death in London. Click here.

Did you enjoy the article? If so, let the world know by clicking on one of the buttons below! Like it, tweet about it, or share it in one of hundreds of other ways!

Bibliography

The Maul and the Pear Tree, Critchley and James, 1971

Thieves’ Kitchen, Donald Low, 1982