In this article, Jennifer Johnstone looks at what Charles Dickens thought about poverty in 19th century Britain. And considers what Dickens may think about modern-day attempts to reduce the size of the British Welfare State.

No one is useless in this world who lightens the burdens of another.

- Charles Dickens

By observing Charles Dickens’ work, what is clear is that poverty is a major theme. Dickens was an outspoken social critic in general, but especially about poverty. Before the birth of Britain’s Welfare State, which aims to support the poor, Dickens sought to help the poor by highlighting the social inequality in his country. In this respect, Charles Dickens was a man ahead of his time. The British Welfare State was founded in 1945, with the aim of providing people with a safety net ‘from cradle to grave.’ Dickens identified the reality of poverty many years before that. He acknowledged that poverty was not the fault of the people who endured it, but rather, the fault of the establishment, including the government. Indeed, I daresay that he would be of the same view today – that poverty is the fault of the government.

Mr Bumble, the beadle from the workhouse, leading Oliver Twist. The painting is based on the book Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens.

How would Charles Dickens view modern poverty?

The short answer is: he would have had as much contempt for the way society treats the poor today as he did when he was alive. With modern Britain vilifying the poor, or those on benefits, Dickens would have seen this as an attack on the poor; instead of society trying to eradicate poverty, society is blaming the poor for something that is outside of their control. Victorian Britain condemned ‘idleness.’ This Victorian attitude is something that we see creeping back into modern society. Since Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, Britain has been slowly eradicating its Welfare State. This weakening of the Welfare State is essentially attacking the poor, because, the poor rely on the Welfare State, whether they are the working poor, or the unemployed poor.

Dickens would have seen this as classism. And condemned it as such. He quite clearly condemns classism in Oliver Twist, and A Christmas Carol. Dickens, in both these works, portrays the rich as greedy, and as people who are unsympathetic to the poor.

The Poor Law

Dickens condemned ‘The Poor Law.’ This law resulted in the middle and upper-classes paying less to support the poor. In much the same way, Dickens would have said that cutting poor people’s benefits in modern Britain, was about punishing the poor. The book A Christmas Carol comes to mind at this point; we can view Scrooge as the symbol of taking more and more from the poor. We can see similarities with the Poor Law, and cuts to unemployment benefits today.

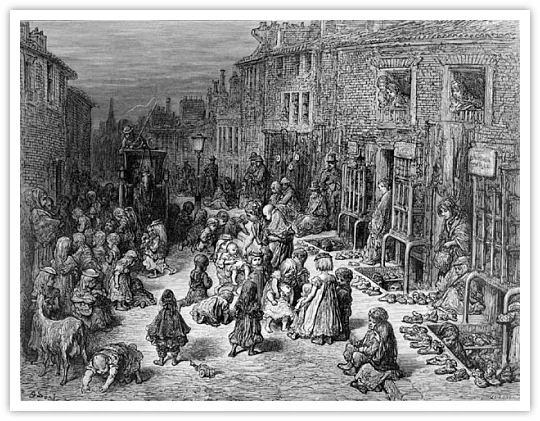

But, was Dickens right, was the Poor Law an attack on those who were poor? I think the answer is yes. The first reason is that The Poor Law attacked the impoverished, and meant that the richest contributed less. The second reason why the Poor Law attacked the poorest was because it forced people into the horrible workhouses. Workhouses were deliberately cruel. Usually one would only enter a workhouse as a last resort; they were internationally hard places to live in, forcing people into work in harsh conditions, even children. Not only that, but, as we see in Oliver Twist, people were not given an adequate living area, and nor were they fed well. Proper nutrition was absent within workhouses, except for the rich who worked in them.

Within the workhouses, people were essentially treated like prisoners; not human beings who were just unlucky enough to be born into poverty. The only seeming difference with workhouses and prisons was that the door was always open with workhouses. But, in reality, people did not have the choice to leave as they had no means to support themselves.

Oliver Twist

Dickens novel Oliver Twist is about an orphan boy. In the novel, Oliver is born within a poorhouse, but his mother dies. Later Oliver is sent to an ‘infant farm.’ Finally escaping the poorhouse, Oliver is sent spinning into the dark underworld of London, working for a gang of thieves led by Fagan and the Artful Dodger, Bill Sykes and Nancy. The reader sees through Nancy’s character, that those who are forced into this criminal underworld (in Nancy’s case - prostitution), are forced into poverty because of the problems in the system. Not only does it destroy their lives, but it also has a negative impact on society at large. We often see Nancy as a sympathetic character, one who tries to get Oliver out of this life of crime. It is interesting that Dickens uses Nancy’s character, as a symbol of domestic abuse. Not only does Nancy represent domestic abuse, but she also seems to be symbolic of the Victorian’s beating down on those who were sympathetic to the poor. It also seems like an indirect criticism from Charles Dickens to the state for having such an attitude.

In Conclusion

Dickens was a writer who often injected his work with realism and social criticism. His work may have included ghosts or time travel (A Christmas Carol), but Dickens work was more about reality than fantasy. And that is what makes Dickens’ novels so memorable; we are being educated about Victorian Britain, but in a way that is engaging to the reader. At the very heart of Dickens’ writing is a very serious message: the tragedy of inequality, poverty, and deprivation. In the second part of my analysis of Dickens, I want to turn to what can only be described as the dark side of Dickens.

Part 2 in this series will follow soon. In the meantime you can read more about crime in 19th century Britain here.

Now, if you enjoyed the article, please like it, tweet about it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below!

References

- http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/bleakhouse/carter.html

- http://classiclit.about.com/od/dickenscharles2/a/aa_cdickensquot.htm

- http://exec.typepad.com/greatexpectations/dickens-attitude-to-the-law.html

- http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/diniejko.html

- http://orwell.ru/library/reviews/dickens/english/e_chd

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-16907648

- http://www.dickens.port.ac.uk/poverty/

- http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/bleakhouse/carter.html

- http://charlesdickenspage.com/twist.html

- http://www.theguardian.com/politics/blog/2012/jan/12/welfare-reform-charles-dickens

- Little Dorrit: http://www2.hn.psu.edu/faculty/jmanis/dickens/LittleDorrit6x9.pdf

- Olive Twist: http://www.planetebook.com/ebooks/Oliver-Twist.pdf

- A Christmas Carol: http://www.ibiblio.org/ebooks/Dickens/Carol/Dickens_Carol.pdf

- The Noble Savage: http://www.readbookonline.net/readOnLine/2529/