It may seem strange, but there is very strong evidence that the White House killed a number of presidents in the mid-nineteenth century. The deaths of Zachary Taylor, William Henry Harrison, and James K. Polk are all linked to something in the White House – although many believed that some presidents were poisoned by their enemies. William Bodkin explains all…

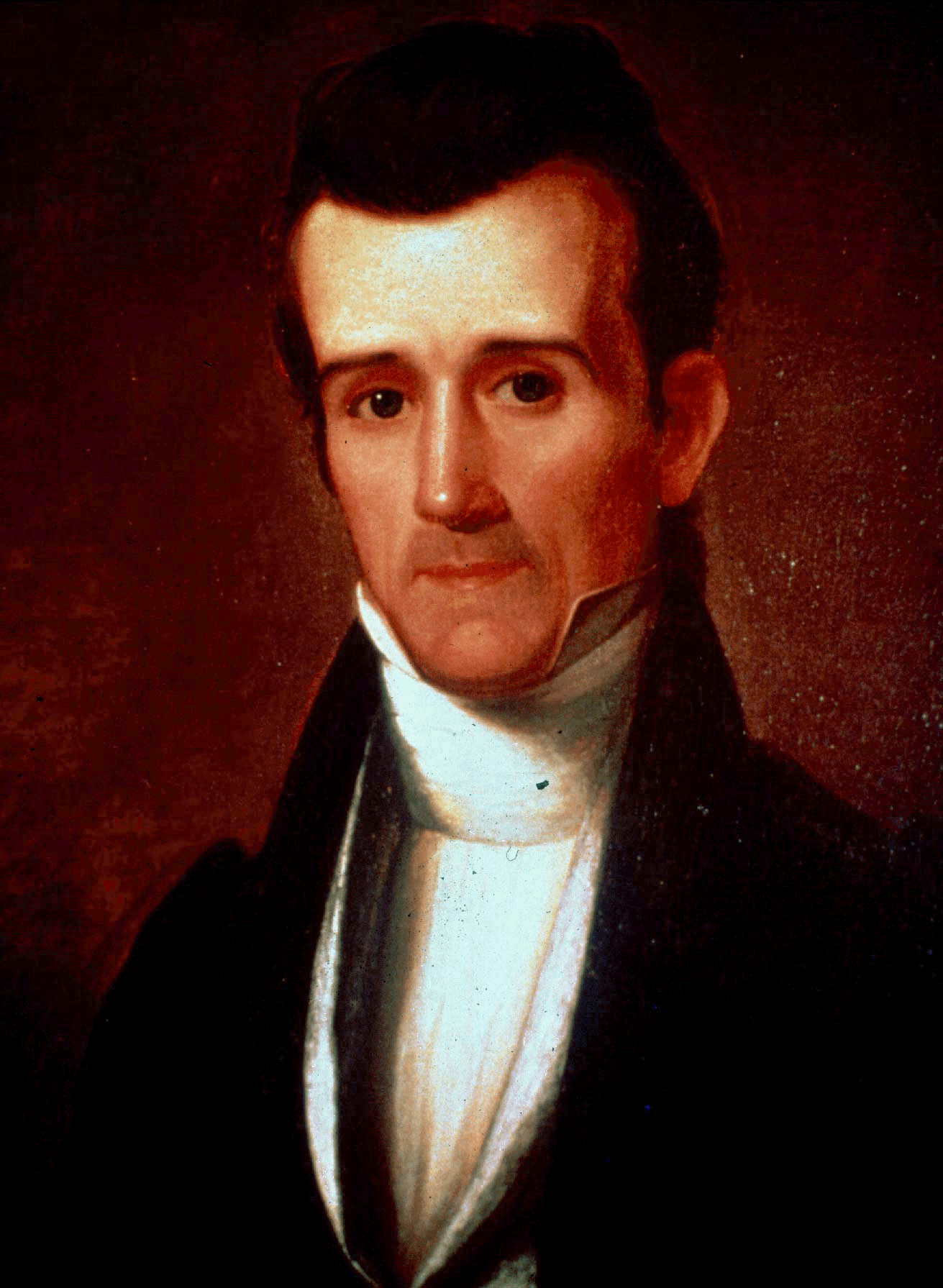

A poster of Zachary Taylor, circa 1847. He is one the presidents the White House may have helped to killed...

President of the United States is often considered the most stressful job in the world. We watch fascinated as Presidents prematurely age before our eyes, greying under the challenges of the office. Presidential campaigns have become a microcosm of the actual job, with the conventional wisdom being that any candidate who wilts under the pressures of a campaign could never withstand the rigors of the presidency. But there was a time, not so long ago, when it was not just the stress of the job that was figuratively killing the Presidents. In fact, living in the White House was, in all likelihood, literally killing them.

Between 1840 and 1850, living in the White House proved fatal for three of the four Presidents who served. William Henry Harrison, elected in 1840, died after his first month in office. James K. Polk, elected in 1844, died three months after he left the White House. Zachary Taylor, elected in 1848, died about a year into his term, in 1850. The only occupant of the Oval Office during that period to survive was John Tyler, who succeeded to the Presidency on Harrison’s death. What killed these Presidents? Historical legend tells us that William Henry Harrison “got too cold and died” and that Zachary Taylor “got too hot and died.” But the truth, thanks to recent research, indicates that Harrison, Taylor, and Polk may have died from similar strains of bacteria that were coursing through the White House water supply.

Conspiracies and Legends

On July 9, 1850, President Zachary Taylor, Old Rough and Ready, former general and hero of the Mexican-American War, succumbed to what doctors called at the time “cholera morbus,” or, in today’s terms, gastroenteritis. On July 4, 1850, President Taylor sat out on the National Mall for Independence Day festivities, including the laying of the cornerstone for the Washington Monument. Taylor, legend has it, indulged freely in refreshments that day, including a bowl of fresh cherries and iced milk. Taylor fell ill shortly after returning to the White House, suffering severe abdominal cramps. The presidential doctors treated Taylor with no success. Five days later, he was dead.

Taylor’s death shocked the nation. Rumors began circulating immediately concerning his possible assassination. The rumors arose for a good reason. Taylor, a Southerner, opposed the growth of slavery in the United States despite being a slave owner himself. While President, Taylor had worked to prevent the expansion of slavery into the newly acquired California and Utah territories, then under the control of the federal government. Taylor prodded those future states, which he knew would draft state constitutions banning slavery, to finish those constitutions so that they could be admitted to the Union as free states.

Taylor’s position infuriated his southern supporters, including Jefferson Davis, who had been married to Taylor’s late daughter, Knox. Davis, who would go on to be the first and only President of the Confederate States of America, had campaigned vigorously throughout the South for Taylor, assuring Southerners that Taylor would be friendly to their interests. But in truth, no one really knew Taylor’s views. A career military man, Taylor hewed to the time honored tradition of taking no public positions on political issues. Taylor believed it was improper for him to take political positions because he had sworn to serve the Commander-in-Chief, without regard to person or party. Indeed, he had never even voted in a Presidential election before running himself.

Tensions between Taylor and the South grew when Henry Clay proposed his Great Compromise of 1850, which offered something for every interest. The slave trade would be abolished in the District of Columbia, but the Fugitive Slave Law would be strengthened. The bill also carved out new territories in New Mexico and Utah. The Compromise would allow the people of the territories to decide whether those territories would be slave or free by popular vote, circumventing Taylor’s effort to have slavery banned in their state constitutions. But Taylor blocked passage of the compromise, even threatening in one exchange to hang the Secessionists if they chose to carry out their threats.

More speculation

Speculation on the true cause of Taylor’s death only increased throughout the years, particularly after his former son-in-law, Davis, who had been at Taylor’s bedside when he died, became President of the Confederacy. The wondering reached a fever pitch in the late twentieth century, when a University of Florida professor, Clara Rising, persuaded Taylor’s closest living relative to agree to an exhumation of his body for a new forensic examination. Rising, who was researching her book The Taylor File: The Mysterious Death of a President, had become convinced that Taylor was poisoned. But the team of Kentucky medical examiners assembled to examine the corpse concluded that Taylor was not poisoned, but had died of natural causes, i.e. something akin to gastroenteritis, and that his illness was undoubtedly exacerbated by the conditions of the day.

But what caused Taylor’s fatal illness? Was it the cherries and milk, or something more insidious? While the culprit lurked in the White House when Zachary Taylor died, it was not at the President’s bedside, but rather, in the pipes.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, Washington D.C. had no sewer system. It was not built until 1871. The website of the DC Water and Sewage company notes that by 1850, most of the streets along Pennsylvania Avenue had spring or well water piped in, creating the need for a sanitary sewage process. Sewage was discharged into the nearest body of water. With literally nowhere to go, the sewage seeped into the ground, forming a fetid marsh. Perhaps even more shocking, the White House water supply itself was just seven blocks downstream from a depository for “night soil,” a euphemism for human feces collected from cesspools and outhouses. This depository, which likely contaminated the White House’s water supply, would have been a breeding ground for salmonella bacteria and the gastroenteritis that typically accompanies it. Ironically, the night soil deposited a few blocks from the White House had been brought there by the federal government.

Something in the water

It should come as no surprise, then, that Zachary Taylor succumbed to what was essentially an acute form of gastroenteritis. The cause of Taylor’s gastroenteritis was probably salmonella bacteria, not cherries and iced milk. James K. Polk, too, reported frequently in his diary that he suffered from explosive diarrhea while in the White House. For example, Polk’s diary entry for Thursday, June 29, 1848 noted that “before sun-rise” that morning he was taken with a “violent diarrhea” accompanied by “severe pain,” which rendered him unable to move. Polk, a noted workaholic, spent nearly his entire administration tethered to the White House. After leaving office, weakened by years of gastric poisoning, Polk succumbed, reportedly like Taylor, to “cholera morbis”, a mere three months after leaving the Oval Office.

The White House is also a leading suspect in the death of William Henry Harrison. History has generally accepted that Harrison died of pneumonia after giving what remains the longest inaugural address on record, in a freezing rain without benefit of hat or coat. However, Harrison’s gastrointestinal tract may have been a veritable playground for the bacteria in the White House water.

Harrison suffered from indigestion most of his life. The standard treatment then was to use carbonated alkali, a base, to neutralize the gastric acid. Unfortunately, in neutralizing the gastric acid, Harrison removed his natural defense to harmful bacteria. As a result, it might have taken far less than the usual concentration of salmonella to cause gastroenteritis. In addition, Harrison was treated during his final illness with opium, standard at the time, which slowed the ability of his body to get rid of bacteria, allowing them more time to get into his bloodstream. It has been noted, that, as Harrison lay dying, he had a sinking pulse and cold, blue extremities, which is consistent with septic shock. Did Harrison die of pneumonia? Possibly. But the strong likelihood is that pneumonia was secondary to gastroenteritis.

Neither was this phenomena limited to the mid-nineteenth century Presidents. In 1803, Thomas Jefferson mentioned in a letter to his good friend, fellow founder Dr. Benjamin Rush that “after all my life having enjoyed the benefit of well formed organs of digestion and deportation,” he was taken, “two years ago,” after moving into the White House, “with the diarrhea, after having dined moderately on fish. Jefferson noted he had never had it before. The problem plagued him for the rest of his life. Early reports of Jefferson’s even death stated that he had died because of dehydration from diarrhea.

Presidents after Zachary Taylor fared better, once D.C. built its sewer system. The second accidental President, Millard Fillmore, lived another twenty years after succeeding Zachary Taylor. But what about the myths surrounding these early Presidential deaths? They were created, in part, by a lack of medical and scientific understanding of what really killed these men. With the benefit of modern science we can turn a critical eye on these myths. But we should not forget that myth-making can serve an important purpose past simple deception. In the case of Zachary Taylor, it provided a simple explanation for his unexpected death. Suspicion or accusations of foul play would have further inflamed the sides of the slavery question that in another decade erupted into Civil War, perhaps even starting that war before Lincoln’s Presidency. In Harrison’s case, that overcoat explanation helped the country get over the shock of the first President dying in office and permitted John Tyler to establish the precedent that the Vice-President became President upon the death of a President. In sum, these nineteenth century myths helped the still new Republic march on to its ever brighter future.

What did you think of today’s article? Do you think it was the water that killed several Presidents? Let us know below…

Finally, William's previous pieces have been on George Washington (link here), John Adams (link here), Thomas Jefferson (link here), James Madison (link here), James Monroe (link here), John Quincy Adams (link here), Andrew Jackson (link here), Martin Van Buren (link here), William Henry Harrison (link here), John Tyler (link here), and James K. Polk (link here).

Sources

- Catherine Clinton, “Zachary Taylor,” essay in “To The Best of My Ability:” The American Presidents, James M. McPherson, ed. (Dorling Kindersley, 2000)

- Letter, Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, February 28, 1803

- Milo Milton Quaife, ed., “Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845-1849” (A.C. McClurg & Co., 1910)

- Jane McHugh and Philip A. Mackowiak, “What Really Killed William Henry Harrison?” New York Times, March 31, 2014

- Clara Rising, “The Taylor File: The Mysterious Death of a President” (Xlibris 2007)