Mary would England into a war against France from 1557-1558, which ultimately proved to be a disaster for England, considering the loss of numerous lives and the loss of the Calais territory. Influenced by her husband, Philip, Mary entered a conflict that was initially contested by Spain and France over territory in Italy, known as the Italian Wars. Mary’s decision to enter the Italian War of 1551-1559 was also a result of two insurrections affiliated with the French by Henry Dudley and later Thomas Stafford. Mary’s involvement put her at odds with the Pope, Paul IV, turning her and the country against the authority of the Catholic Church, a relationship she had worked so hard to once again obtain. This would ultimately tarnish her reputation.

Prior to entering the Italian War of 1551-1559, France and Spain had long engaged in a war over claimed territories in Italy. Beginning in 1494, the Italian War dominated a majority of the sixteenth century, with a frequent back-and-forth between Emperor Charles V of Spain and the Valois kings of France.[1] Both countries continued lobbying for the support of the English, which placed England in the middle to serve as a potential ally to either of the two countries. All three countries depended on each other for trade. England and France exchanged grain in order to prevent food shortages. Spain heavily relied on access to the English Channel, which connected Spain to the Netherlands, another important country for trade, which was also a Spanish-controlled area.[2] Mary recognized the importance of forging peace between England and Spain in order to maintain access to the benefits England could receive through trade. Furthermore, Mary and Philip’s act of marriage prevented her from involving England in any conflict between France and Spain.[3] The act of marriage states:

The realm of England, by occasion of this matrimony, shall not directly or indirectly be entangled with the war that is between the most victorious lord the emperor, father unto the said lord prince, and Henry, the French king, but he the said lord Philip, as much as shall lie in him, on the behalf of the said realm of England, shall see the peace between the said realms of France and England observed, and shall give no cause of any breach…[4]

This statement from the act of marriage reaffirmed that Mary could not involve England in the current conflict happening between Spain and France. Mary initiated treaty negotiations in 1555; unfortunately, nothing resulted from these negotiations due to each country refusing to give up land the other had requested.[5] Despite this initial failure, negotiations continued, and Spain and England did ultimately obtain brief peace through the treaty of Vaucelles in February 1556.[6]

Not keeping the peace

However, the treaty of Vaucelles would not keep the two countries from eventual conflict due to interference from the Catholic Church. The newly elected Pope, Paul IV, was described as a “bitter foe” of the Spanish due to their rule of his native Naples. Overall, Paul was against Spanish control in Italy due to his overwhelming fear that the Spanish were a threat to the Papacy’s independence and authority.[7] Paul openly expressed his disdain by labeling Charles V as “heretic, schismatic, and tyrant” and asserting that Philip, who now assumed power after Charles abdicated the throne in 1556, was the same.[8] Paul stated that Charles, and now Philip, was attempting to take the lands away from the papacy to continue to amass their own wealth, and as he also stated, to “oppress the Holy See,” meaning to take away the authority and power of the Catholic Church.[9] Philip reacted to this denouncement of both himself and his father by prompting an invasion by his viceroy, the duke of Salva in Naples, of the Papal States in September 1556.[10] France had signed a secret treaty with the papacy in December of 1555 that promised them control of Naples if they could force out the Spanish.[11] They countered this attack through a surprise invasion of one of the Spanish occupied lands of Douai, France in January of 1557.[12] Thus, the treaty of Vaucelles was officially broken, war was declared, and Philip returned to England in March of 1557 to ask the assistance of his wife Mary.[13]

Mary’s hands were tied. Both France and Spain were allies to England, and the marriage act prevented Mary from placing England in the conflict between the two countries. Additionally, Mary and her council were concerned that if England were to assist the Spanish, they would be cut off from access to grain and wool from France.[14] The harvests responsible for supplying a vast majority of food within England were particularly horrendous in both 1555 and 1556, resulting in shortages of food and rises in prices due to scarcity. Maintaining trade with France was crucial in order to supply the people of England with food.[15] There was additional concern that assisting the Spanish would lead to France prompting Scotland to invade England, and Ireland, controlled by England at the time, to rebel against England.[16]

Choosing Spain

Despite these factors, due to preexisting French hostilities between France and England, as well as her marriage to Philip, Mary was more inclined to pursue assisting Spain against France. For example, prior to Mary’s ascension to throne, Henry II supported the Duke of Northumberland’s choice of Jane Grey as the successor of Edward VI due to Mary’s inclination towards the Spanish.[17] Another event that continued to sour Mary’s sentiment towards the French occurred in 1556: Henry Dudley, who allegedly conducted a conspiracy in France with French influence, was discovered attempting to steal from the Exchequer and invade England due to hatred of the Spanish and his favor of Mary’s sister, Elizabeth.[18] The conspiracy was defeated, and the French ambassador who was suspected in the plot, Antoine de Noailles, was dismissed from the English court.[19] England did eventually decide to assist Spain and declare war on France when nobleman Thomas Stafford arrived in England on April 23rd, 1557 with two French warships; combined with French and English rebels, they seized Scarborough castle with between 30 and 100 men.[20] Stafford further intended to dispose of Mary, declaring that she was “handing the country to foreigners.” He also added that the crown needed to be “kept in English blood,” and declared his right to the throne.[21] Mary and her council were informed four days later, and on April 28th the insurrection was defeated.[22] This event, along with the improved harvest in May of 1557, which meant England was not dependent on France for grain, allowed the council to officially declare war on France on June 7th, 1557.[23]

Although many still feared a break from France would have negative effects on England, there were some of Mary’s subjects who supported the war. For example, William Paget, the serving Lord Privy Seal and strong supporter of the marriage of Mary and Philip, was eager to get into the field of battle.[24] Support for the war was also derived from national pride and support of the King and Queen. For example, a Scottish Earl stated in a conversation with the earl of Westmorland, “I am no more French than you are a Spaniard,” to which Westmorland replied, “as long as God shall preserve my master and mistress together, I am and shall be a Spaniard to the uttermost of my power.”[25] This conversation insinuated that as long as they were able to maintain the safety of their monarchs and their way of life in England, they would be willing to fight. Furthermore, support for the war was created due to the job opportunities and profit it offered.[26]

At the start of the war, things looked optimistic for Mary and Philip. For example, large focus was placed on improving the navy. Initially rising to prominence in the early 1540s, the navy suffered under the regime of Edward VI, when economic issues resulted in Edward’s government having to sell off war ships in order to garner money for the government, thus downsizing the navy.[27] By the time war was declared during Mary’s reign, twenty new ships had been constructed.[28] By July of 1557, approximately 7,000 men were across the English Channel, and allied with the Spanish fleet, they were able to successfully clear out French ships from the channel.[29] Further victories came in August and October of 1557. One of these was the Battle of St. Quentein. On August 10th, 1557, Englishmen, as well as Spanish and Imperial forces, were able to capitalize on the mistake of the French Constable, Anne de Montmorency, and successfully break through French forces, killing 3,000 French troops as well as capturing 7,000 others, and eighteen days later they were able to take the town.[30] Additionally, the French were able to convince the Scots to join their forces. Mary of Guise, who was serving as Regent of Scotland, due to her daughter living in France, hoped to also maintain French support, which contributed to her aligning with the French.[31] The two forces first met in October of 1557, which saw the English emerge victorious.[32] Both Mary and Philip rejoiced as the war was seemingly progressing in their favor. However, as the war continued, things would soon begin to unravel.

Changing Fortunes

Despite their initial success, Mary and Philip’s luck ran out as the war progressed. Although the English and Spanish forces were victorious at the battle of St. Quentein, it can be argued that from an early point there was the foreshadowing of a negative outcome for the English. For example, according to casualty statistics from the treasurer, Mary supplied more men in battle than the Spanish.[33]

However, each group endured various circumstances that hindered their abilities in battle and the effectiveness of a large majority of English subjects in service. For example, out of the 4,148-foot soldiers, 417 were sick, 137 hurt, and 108 were discharged due to the severity of their sickness.[34] Additionally, the English were ill equipped with weapons, food, and money. These were provisions necessary for the English to handle a “large-scale” and surprise attack from the French. Absence of these provisions would prove to be detrimental for the English during the French attack on the English controlled town of Calais.[35]

The French were initially skeptical about deciding to attack the town of Calais. Calais was described as an “isolated fortress.”[36] It was protected by a series of smaller forts and benefited from its geographic location. To approach the town from the north, the French would encounter the fortress of Rysback that guarded Calais. Rysback, which bordered the English Channel was also surrounded by a marsh, which made it virtually impossible to penetrate the fortress.[37] Attempting to capture the town from the south also seemed impossible due to its protection by a fortress at Newnham Bridge, also called Nieulay by the French.[38] Despite the obstacles, King Henry II attempted to gain revenge from the loss of St. Quentein by calling upon the Duke of Guise, the brother of Mary de Guise and commander of the French army, to attack and claim Calais.[39] Furthermore, Antoine de Noailles, the former French ambassador to England, described that Calais possessed a large level of Protestant activity, and projected that any attempts by the French to claim Calais would be seen as favorable by the people living there.[40] In an attempt to take Calais, the Duke of Guise devised a plan.[41]

The Attack on Calais

In December of 1557, it was officially decided by the French to attack Calais while the Duke of Guise would also attack Calais from the south, separate his troops, and attempt to take the town from both sides. This plan would eventually prove to be successful.[42]

News of France’s intentions to attack Calais spread to the English government by December 22nd, 1557.[43] During this time, the English government was in the midst of reducing its army due to the fact that, historically, no attacks took place in December or January because of the holiday and weather conditions; additionally, peace was usually negotiated at this time.[44] On December 29th, Wentworth mistakenly wrote to Queen Mary I that the French were not targeting Calais when he heard of their presence in another one of Philip’s fortresses in France; he stated “the enemy's power is already planted before New Hesdin, where the French King is shortly looked for.”[45] This miscalculation would prove to be costly, as 27,000 men of the Duke of Guise’s forces arrived at Newnham Bridge on January 1st, 1558, while another group of Guise’s men simultaneously crossed the frozen marshes and arrived at Rysback the same day.[46] French forces were able to successfully defeat the English forces at Rysback on January 2nd and then Newnham Bridge on January 4th to finally proceed to Calais. Outnumbered, Lord Wenworth surrendered the town of Calais to the French on January 7th, 1558.[47]

Philip recognized that the loss would weaken both the English desire to continue to engage in a war in Europe as well as his own reputation in England.[48] People speculated that Philip purposely allowed Calais to fall so that he could conquer the territory himself.[49] This was widely debated due to Philip’s fervent pleas to the Privy Council to send troops to reclaim Calais as well as his mournful statements of the loss. Philip lamented, “That sorrow was unspeakable, for reasons which you well imagine and because the event was extremely grave one for those states.”[50] The cost of the war had drained Mary’s ability to afford to send more troops. At the start of the war, taxes had been raised to four times the normal rate on goods in order to accumulate £ 300,000.[51] Although the amount was achieved, immediate payments towards both weapons and soldiers quickly drained their expenses, which meant there was no more money in reserve. In order to avoid a taxpayer strike, Parliament refused to raise taxes, and denied the requests for reinforcements in March of 1558.[52]

Turning away from Mary

Coinciding with the loss of English morale was Mary’s declining popularity. Following the loss of Calais, soldiers soon began deserting their posts due to their lack of faith in Mary’s ability to recover from the loss. Additionally, soldiers and sailors also began deserting the army and navy due to Mary’s inability to pay their salaries, which led to a proclamation labeling desertion as a felony.[53] One of Mary’s subjects, Robert Cockrell, was executed for stating, “he would serve the French King before he would serve the Queen’s Majesty.”[54] John Knox, a Protestant reformer who was forced to retreat to Geneva, Switzerland during Mary’s reign, published The First Blast of the Trumpet the Monstrous Regiment of Women. Although the overall rhetoric of the publication was that women should not rule over men in all aspects of life, Knox used Mary as an example to justify his argument and commented on her marriage to Philip:

[55]Wonder it is, that the advocates and patrons of the right of our ladies did not consider and ponder this law, before they counseled the blind princes and unworthy nobles of their country to betray the liberties thereof into the hands of strangers: England, for satisfying of the inordinate appetites of that cruel monster Mary (unworthy, by reason of her bloody tyranny, of the name of a woman), betrayed, alas! to the proud Spaniard…

Knox commented that women should be wary of whom they marry. Additionally, he accused her of handing over the “liberties” of the English people to a “Spaniard,” and compared her to a “monster.”[56] Furthermore, Mary’s failure to secure Calais resulted in fear of a French invasion throughout the spring and summer of 1558 in England.[57] Mary’s health was also rapidly declining during this time; with her chances of survival low, Philip recognized that Elizabeth was next in line to the throne. In order to maintain an alliance with England, he secretly offered marriage to Elizabeth.[58] However, Elizabeth refused as she believed that, “the queen had lost the affection of the people of this realm because she had married a foreigner.”[59] Whether Mary knew of this is unknown; however, during this time and throughout the later months of that year, Mary’s health continued to rapidly decline, and on the morning of November 17th, 1558, Mary passed away at the age of forty-two.[60]

England’s involvement in the French War ultimately demonstrated how foreign influence was detrimental to Mary’s reign. Philip’s goading and Mary’s willingness to please her husband led to England’s involvement in a long standing rivalry between the French and Spanish. Although the war was initially successful, the outcome was ultimately a disaster with England losing Calais to the French. With the loss came the continued decline of Mary’s popularity, which plagued her reputation until her death.

What do you think of Queen Mary I of England? Let us know below.

Bibliography

Secondary Sources

Davies, C.S.L. England and the French War. In The Mid-Tudor Polity, 1540-1560, edited by Jennifer Loach and Robert Tittler, 159. London, England: Macmillan Press, 1980.

Loades, D. M. Mary Tudor: A Life. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

Loades, D. M. The Reign of Mary Tudor: Politics, Government, and Religion in England, 1553-1558. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1979.

Porter, Linda. Mary Tudor: The First Queen. London, England: Portrait, 2007.

Tittler, Robert. The Reign of Mary I. London: Longman, 1983.

Whitelock, Anna. Mary Tudor: England's First Queen. London: Bloomsbury, 2009.

Primary Sources

"'Act for the Marriage of Queen Mary to Philip of Spain (1554).'" Last modified 1920. http://rbsche.people.wm.edu/H111_doc_marriageofqueenmary.html -.

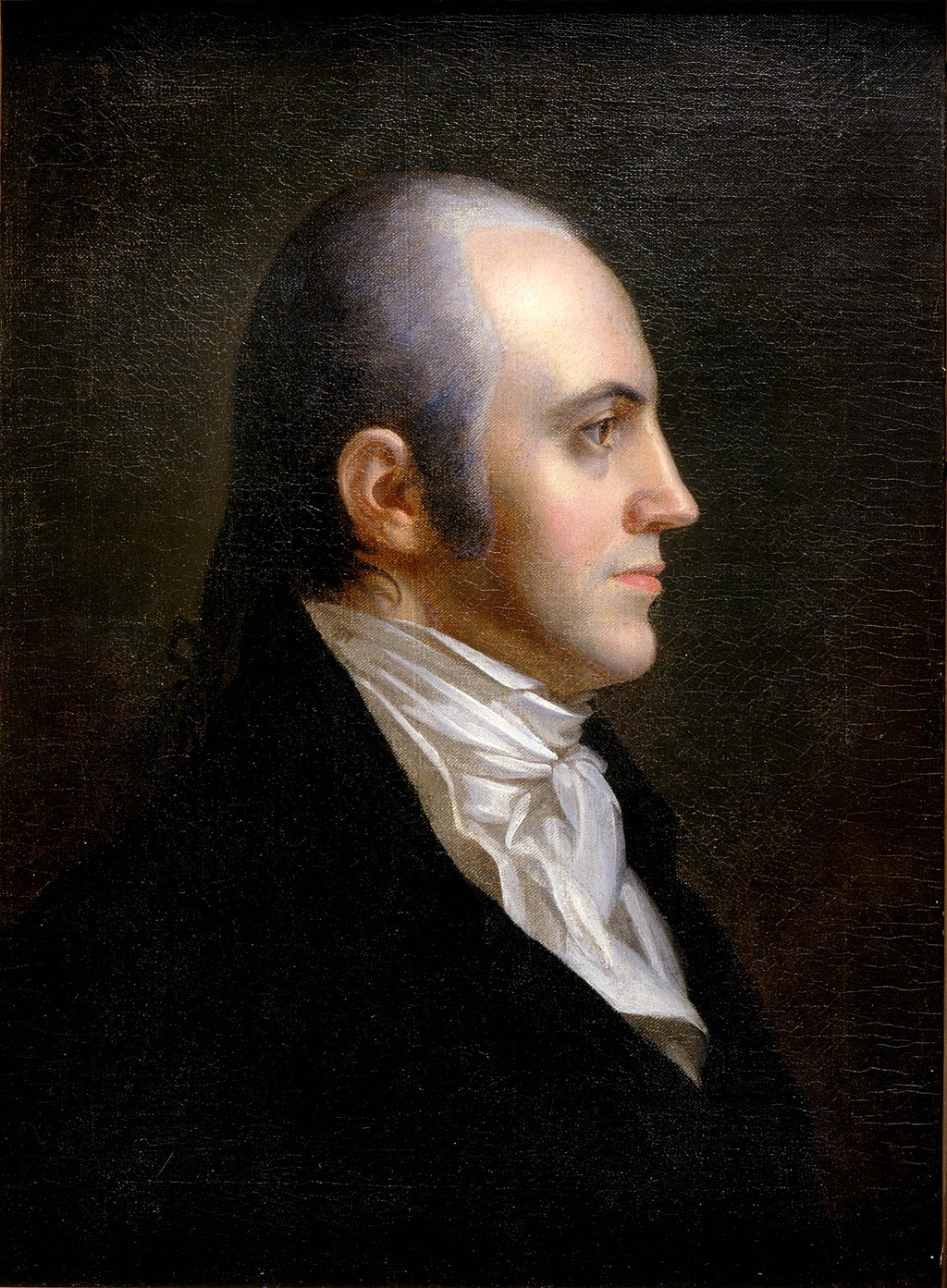

Eworth, Hans. Mary I and Philip II of Spain. 1558. Oil on Panel. Woburn Abbey, Woburn, Bedfordshire, England.

"Mary: August 1554," in Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Mary 1553-1558, ed. William B Turnbull (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1861), 110-117. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/foreign/mary/pp110-117

"Mary: December 1557," in Calendar of State Papers Foreign: Mary 1553-1558, ed. William B Turnbull (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1861), 346-354. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/foreign/mary/pp346-354.

Knox, John. The First Blast of the Trumpet the Monstrous Regiment of Women. N.p., 1558. http://www.swrb.ab.ca/newslett/actualNLs/firblast.htm.

[1] C.S.L. Davies. England and the French War. In The Mid-Tudor Polity, 1540-1560, edited by Jennifer Loach and Robert Tittler, London, England: Macmillan Press, 1980, 159.

[2] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 160-161.

[3] Titler, The Reign of Mary I, 68.

[4] "Act for the Marriage of Queen Mary to Philip of Spain (1554)." Act for the Marriage of Queen Mary to Philip of Spain (1554). http://rbsche.people.wm.edu/H111_doc_marriageofqueenmary.html.

[5] Titler, The Reign of Mary I, 68.

[6] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 160.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Titler, The Reign of Mary I. 68

[11] Ibid.

[12] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 161.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Titler, The Reign of Mary I, 69.

[15] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 161.

[16] Titler, The Reign of Mary I, 69.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Loades, Mary Tudor: A Life, 261. The Exchequer was a department that managed the royal revenue.

[19] Ibid, 262.

[20] Loades, The Reign of Mary Tudor: Politics, Government, and Religion in England, 1553-1558, 365.

[21] Ibid, 366.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 162.

[24] Ibid, 162.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 162-163.

[27] Ibid, 164.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Titler, The Reign of Mary I. 72

[30] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 164.

[31] Titler, The Reign of Mary I, 73.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 166.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid, 167.

[36] Ibid, 169.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid, 168.

[40] Ibid, 169.

[41] Figure 3 in Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 171.

[42] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 170.

[43] Ibid,173.

[44] Ibid,170.

[45] "Mary: December 1557," in Calendar of State Papers Foreign: Mary 1553-1558, ed. William B Turnbull (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1861), 346-354. British History Online, accessed September 13, 2016, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/foreign/mary/pp346-354.

[46] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 172.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Porter, Mary Tudor, 396.

[49] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 176.

[50] Porter, Mary Tudor, 396.

[51] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 180.

[52] Porter, Mary Tudor, 396.

[53] Davies, England and The French, in The Mid-Tudor, 179.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Knox, John. The First Blast of the Trumpet the Monstrous Regiment of Women. N.p., 1558.

[56] Knox, “The First Blast of the Trumpet the Monstrous Regiment of Women.”

[57] Porter, Mary Tudor, 401.

[58] Ibid, 405-406.

[59] Ibid, 406.

[60] Ibid.