The varsity sports teams at the University of Notre Dame are called ‘The Fighting Irish’. Thousands of Irish pubs have sprung up across the world; the Irish are notorious for their drinking. Where did these stereotypes come from? Have the Irish always been thought of in this way?

Becky Clark considers these questions and explains what happened when many Irish people immigrated to England in the nineteenth century.

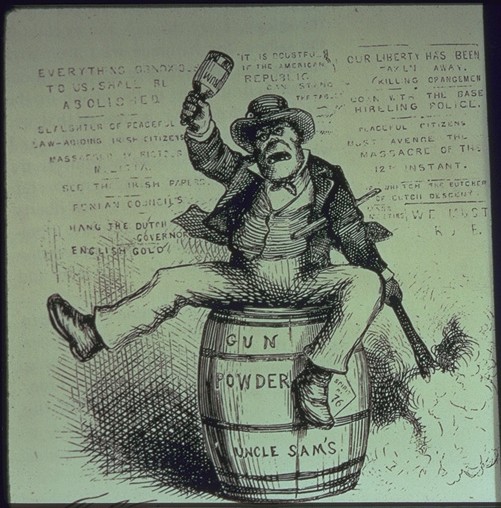

An American anti-Irish cartoon, The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things, by Thomas Nast from Harper's Weekly in 1871.

Today, the Irish are known for being friendly, fun, and the best drinking companions; in reality, the Irish stereotype has fluctuated throughout history.

The truth is, most people know very little about the history of Ireland. Most of us recognize St Patrick’s Day; some of us might know that there was a potato famine, and others probably have snippets of information to pull out about the IRA. What most of us don’t realize is that Britain was the source of a great deal of anti-Irish sentiment in the nineteenth century. It’s something that maybe isn’t taught about as much as it should be, but equally something that we should really be aware of.

I didn’t really come across much Irish history until my fourth year of university, when I started to learn more about the great famine of Ireland in the mid-nineteenth century. I discovered that poverty was rife in Ireland in the nineteenth century; only a quarter of the population were literate, and life expectancy was a mere 40 years of age. A majority of the Irish peasants subsisted on a diet of mainly potatoes. When the leaves suddenly turned black and the crops began to die, peasants struggled to find an alternative to replace it. Calls for help to the British government only met a response of a ‘laissez-faire’ approach. The result was that an estimated one million people died from starvation. Hundreds of thousands more emigrated in the hope of a better life. 200,000 Irish immigrants a year between 1849 and 1852 travelled across the sea, causing cities like Manchester, Glasgow and London to be cast as ‘Little Irelands’.

However, their reception upon arrival was hostile and unwelcoming. Workplaces began to advertise jobs in their windows with the words: ‘Irish need not apply’. Newspapers began to publish stereotype images of ‘Paddy’, the Irish Frankenstein: unhygienic, violent, ungrateful and inherently criminal. Where did this hostility come from? The ‘paddy’ of the early nineteenth century had been presented as somewhat of a lovable rogue. Several factors could be induced for causing this hostility – anti-Catholicism, the perceived contagious degrading nature of the Irish, and the accusation that they were taking English jobs – but these all aligned under one overarching aspect: the consequence of timing. These masses of Irish immigrants arrived into a country besieged by economic, religious and social problems, and one that was looking for a reason on which to pin these problems. The Irish immigrants provided a ready-made scapegoat.

‘They’re taking our jobs’

This one might be familiar to you. It’s one that comes out in any time of economic crisis, when financial stability is under threat. You might be interested to know that this one goes back centuries; working class English people lamented the arrival of the Irish for fear that they were a threat to the security of their own jobs and income. Due to the extent of their poverty, these Irish immigrants were often willing to work any kind of job; longer hours, for less pay, and in worse conditions than their British counterparts. One ballad outlines:

‘When work grew scarce, and bread was dear,

And wages lessened too,

The Irish hordes were bidders here,

Our half paid work to do.’

In effect, the Irish immigrants provided a ready-made target for the frustrations of a class suffering from the job insecurity and poor living conditions of a newly industrialized state.

‘Degrading influence’

Britain was still undergoing industrialization when the influx of Irish arrived, and the symptoms of any industrializing state are squalor and misery. Industrial Britain proved a troublesome and unsanitary place for the lower classes. Living standards were low; disease, overcrowding, poor sanitation and consequent crime made life difficult in the bigger cities. The arrival of the Irish provided an easy scapegoat for this poverty: they were blamed for bringing degrading characteristics with them to pollute England. Inflated rents, a lack of accommodation and the general hostility of the community forced the Irish to overcrowd in poorly conditioned houses far from the city, forming what the English perceived as ‘ghettos’.

These ghettos were usually associated with high levels of drinking (due to the Irish drinking culture), casual violence, vagrancy, diseases and high levels of unemployment. Social investigators were horrified at the extent of violence they found. Rather than addressing the problems of industrial Britain, however, they tended to blame the Irish for their ‘degrading influence’. Nowadays, we know that political prejudice resulted in the Irish being vastly over-represented in crimes. At the time, however, people feared not only the squalor of the Irish, but that their habits would be a contagion, spreading to the lower classes.

In reality, this was not the spread of the contagion of Irish character, but the spread of poverty. Once again, anti-Irish sentiment was whipped into a frenzy, concealing the true root of the problem. It is interesting to see this technique of scapegoating those in the worst position for the country’s problems, particularly because it is a debate that we may still find in societies today.

‘No Immigrants. No popery’

Protestantism was the dominant religion in England in the nineteenth century, and this type of Protestantism was predominantly anti-Catholic. Loyalty to Rome was believed to compromise loyalty to the state, and people feared that the Catholic Irish were doing just that.

With the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850, ‘No Popery’ processions emerged throughout England and, on bonfire night, Catholic effigies were burned in numerous cities. The 1852 Stockport Riots are thought to have been prompted by anti-Catholicism, yet 111 of the 113 arrests were Irish – it became clear for many who the problem was. Religious conflict came to be associated with the perceived violent nature of the Irish. They had arrived into an environment already strongly anti-Catholic, at a time when people feared a revival of Catholicism. A good deal of the hostility towards these immigrants stemmed from a strong suspicion of their religion, which usually accompanied growing national sentiments.

An incomplete history?

It is surprising that the relationship between Ireland and England – from its early origins to the modern day – is so unknown in our historical and cultural imagination. Maybe it has something to do with the reason why British Imperial History is not a popular topic either. A friend had studied history for a year in Dublin; when she came back she told me that she was shocked by the long history between Ireland and Britain, of which she had hardly known about it. ‘It ought to be taught in schools,’ she told me. I agreed. We should study history as it happened – the good things and the bad. The moments that we can be proud of, and those that we cannot.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below…

References

De Nie, Michael, The Eternal Paddy: Irish Identity and the British Press, 1798-1882, (Wisconsin, 2004)

Finnegan, Frances, Poverty and Prejudice: A Study of Irish Immigrants in York 1840-1875, (Cork, 1982)

MacRaild, Donald, Irish Migrants in Modern Britain 1750-1922, (London, 1999).

https://radicalmanchester.wordpress.com/2010/04/08/stockport-riot-june-1852/ [last accessed April 17, 2016]

http://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/famine/introduction.htm