Historiography is composed of the principles, theories, or methodology of scholarly historical research and presentation. Here, James Zills looks at the consensus school in mid-20th century American historiography. He also considers the differences between the consensus and progressive schools of thought.

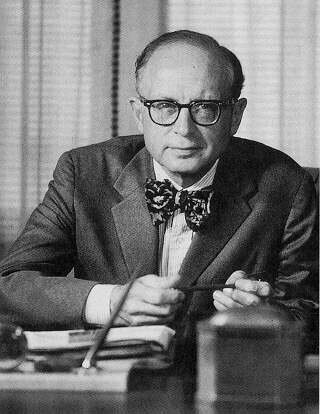

Daniel J. Boorstin, one of the leading figures in Consensus historiography.

The 20th century saw four schools of historical thought that impacted historiography, with some giving conflicting viewpoints and a desire to achieve opposing goals. In the United States, similar to some other countries, those opposing viewpoints come in the form of the New Left historians (progressive) and traditional viewpoints. Focusing on what has gone right as a viewpoint in historical writing serves to instill national pride, lifts a country up as one people, and unifies citizens to progress as a whole. The consensus school of history from the 1940s through the mid-1970s stressed that the shared ideas of Americans far outweighed the internal discourse of Americans. Consensus history made an impact on American values in the 20th century and played a crucial role in the developmental success of the nation, celebrating America’s rise as a national power, and advocated for the continuation of success.

By the end of 1945, the United States had cemented its status as a superpower by defeating the Axis Powers in World War II. With American servicemen on their way home, national pride was high, and the country was well on its way to an economic boom. Nationalism as a school of thought is not a new concept, as it existed in the works of Europeans historians of the 19thcentury. Prior to the consensus school of thought, American historians established the nation’s identity through national pride.[1] American nationhood was alive and well at the beginning of the 20th century when historians were celebrating national pride through the success of American expansionism. The assertion of power through the acquisition of Hawaii, establishing dominance over the Spanish Empire, and control of the Panama Canal renewed enthusiasm for Manifest Destiny.[2]

UNITY OF VALUES

Despite the many accomplishments Americans enjoyed as a whole, Progressive historians would dominate the first half of the 20th century. Their focus on class and sectional conflict brought about divisiveness in America through racial and social class ideologies. Instead of riding the achievements of America as one people, the Progressive historians broke the population down into categories of race, gender, class, and what they perceived as privileges from certain members of society. Progressives borrowed from the fields of sociology, economics, and psychology to interpret their version of history and advocate for reform. The resurgence of traditional history is credited to Richard Hofstadter and, with the joining of other prominent historians of the time, the consensus school of history brought with it a renewed sense of populism.[3]

The impact of historical research presented to the public plays a pivotal role in the way the population views itself, much like any other field of study. Consensus historians believed that the social progress of subjects was of far greater value than the internal conflicts of America.[4] This school of history brought about nearly two decades of uncomplicated patriotism and gave Americans a sense of pride, and political figures they could look up to. Racism, corruption, sexism, and America’s other internal problems, while not addressed, were not ignored as if they didn’t exist. People lived those experiences on a daily basis in the two decades of consensus history. The population needed something uplifting, something to give them a sense of pride, and something to work for. The constant reminder delivered by Progressives only served to drive the nation further apart, by destroying the one thing that could unite America - the country itself.

The absence of social problems brought strong criticism to consensus history from progressives. The disdain progressives have for consensus history can best be summed up by Ribuffo, where in his journal article “What is still living in “consensus” history and pluralist social theory, he says, “…the ghostly echoes are nearly drowned out by louder sounds in contemporary intellectual life.”[5] In this particular article the author questions what is dead and what aspects of consensus history still survive. Ribuffo, in his celebration of the death of consensus history, he asserts that this type of history is “extreme” as well as deluded and dangerous.[6] The approach Ribuffo takes to express disdain for consensus history was by making his criticism a personal attack, an all too familiar theme with progressive viewpoints. It was never the intent of consensus history to solve the social issues of the country, but only to bring us together under nationhood.

Consensus historiography aided in educating two generations of patriotic citizens who were proud Americans - and to some extent united. The school of consensus history was inclusive with historians holding both liberal and conservative political ideologies. Consensus historians describe the world as an operative whole with its shaping credited to the ideals and shared life experiences of its peoples.[7] According to the viewpoint of consensus history every individual within the confines of the borders of the United States plays a unique role in the shaping and the history regardless of their social classification. The contrasting differences in consensus and progressive history are astounding. Consensus history, with its sense of national purpose, showed the uniqueness of the country and its differences with Europe.[8] While consensus history faded away in the mid-1970s, it left a lasting effect, and a large portion of the population still subscribe to the notion of nationalism, thanks to consensus history.

STILL RELEVANT

Consensus history still resonates with historians and citizens today. A perfect example of the impact consensus had on America is the story about the aftermath of a series of violent storms that killed seventy-seven people and caused $300 million in damage to the city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. At the time of the floods Johnstown was no longer the steel-town it once was, with steel workers who once filled the restaurants on Main Street being replaced by bankers, nurses, and retail workers.[9] Long gone were the days when big steel companies like Bethlehem Steel invested in the town. There was an overbearing sense of nostalgia, a longing for the past where people knew one another and cared. The citizens knew that the key to survival was image, one that would give us an image of the past with a view of the future.[10] By celebrating their past through museums, refusing to be a town of shuttered factories, and sharing a unity for pride in their city, the people of Jonestown were able to hold onto their past while attracting future economic opportunities.

Consensus history as a school of thought and viewpoint on what was relevant made a major impact on society in America in the 1940s to the mid-1970s. It was a revival of 19th century institutional history through national pride. Consensus (traditional) history and historiography’s impact on American values in the 20th century played a crucial role in the developmental success of America, celebrating America’s rise as a national power, and advocated for the continuation of success. Without nationhood there would be no motivation to better ourselves as a society. Dismissing the great achievements made by the people as a whole in the country and saying that all is wrong serves to divide the nation and poses a threat to the positive progress and survivability as a nation.

What do you think of 20th century American historiography? Let us know below.

Now you can read James’ article on Ancient Greek historiography here.

[1] Ernst Breisach, Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, 3rd ed (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 309.

[2] Ibid, 310.

[3] Robert D. Johnston, "The Age of Reform: A Defense of Richard Hofstadter Fifty Years On." The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 6, no. 2, (April 2007), 129. Accessed December 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25144472.

[4] Michael Bentley, Modern Historiography: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 1998, 100.

[5] Leo P. Ribuffo, "What Is Still Living In "Consensus" History and Pluralist Social Theory." American Studies International 38, no. 1 (February 2000), 42.Accessed December 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41279737.

[6] Ibid, 43.

[7] Breisach, Historiography, 385.

[8] Ibid, 389.

[9] Don Mitchell, "Heritage, Landscape, and the Production of Community: Consensus History and Its Alternatives in Johnstown, Pennsylvania," Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 59, no. 3 (July 1992), 200. Accessed December 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27773545.

[10]Ibid

Bibliography

Bentley, Michael. Modern Historiography: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 1998.

Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval & Modern. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994

Johnston, Robert D. ""The Age of Reform": A Defense of Richard Hofstadter Fifty Years On." The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 6, no. 2 (2007): 127-37. Accessed December 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25144472.

Mitchell, Don. "Heritage, Landscape, and the Production of Community: Consensus History and Its

Alternatives in Johnstown, Pennsylvania." Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 59, no. 3 (1992): 198-226. Accessed December 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27773545.

Ribuffo, Leo P. "What Is Still Living In "Consensus" History and Pluralist Social Theory." American Studies International 38, no. 1 (2000): 42-60. Accessed December 17, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41279737.