Charity Lamb (c. 1818-1879) was infamous in her time for the being the first woman convicted of murder in the new Oregon territory (the territory in the north-west of the United States). Here, Jordann Stover returns and tells us about the murder, Charity’s trial, and the aftermath.

You can also read Jordann’s article on Princess Anastasia Romanova, the youngest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II here, and on Princess Olga ‘Olishka’ Nikolaevna, the Eldest Daughter of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia here.

The Oregon Hospital for the Insane, where Charity Lamb spent her years from 1862.

Charity Lamb -- we do not know the exact date of her birth or what she looked like. We have photos of the asylum she spent the rest of her days confined to, photos of her lawyer but there is nothing of the woman herself. She was born around 1818 and died some sixty years later. She was convicted of murder, the first woman to recieve such a conviction in the new Oregon territory after she plunged an axe into her husband, Nathaniel’s, skull.

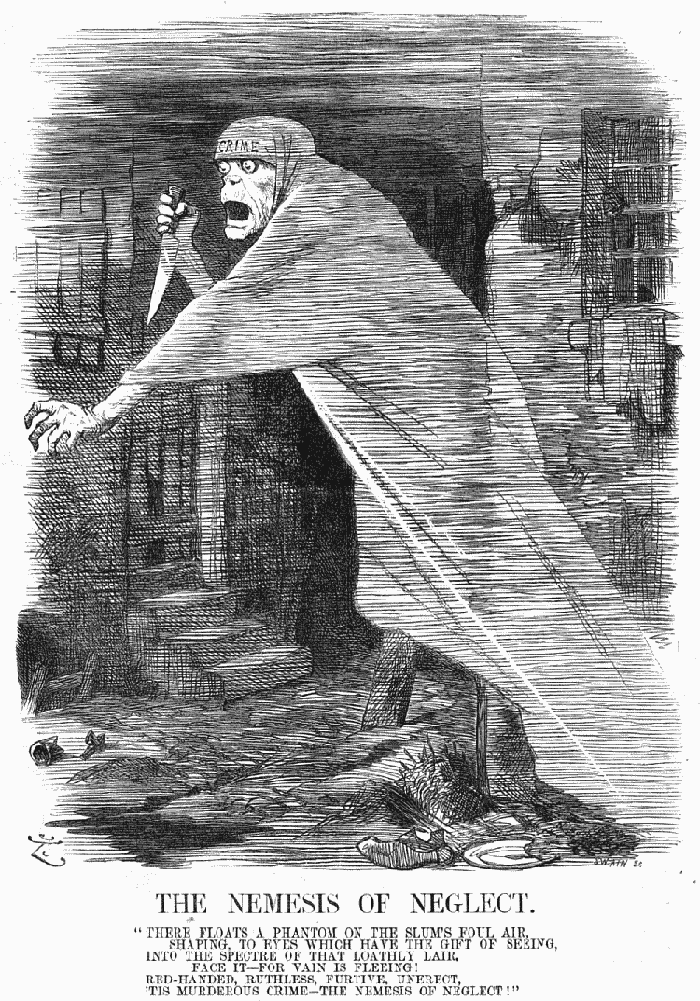

Humans have always had an inherent curiosity for crime, the deadlier the better. We find ourselves captivated by blood spatter and ballistics, by the process of getting into the mind of the world’s most violent individuals. Just as we have done and continue to do in the face of horror, Charity Lamb’s case was sensationalized by the world around her. There were talks of love triangles, insanity, infidelity, and more. The Oregon territory would have had you believing that Lamb was certifiable, that she was a woman lusting after a young man under her husband's (and daughter’s) nose. She, who was almost certainly a housewife who led a monotonous, ordinary life up until the beginning of this fiasco, was seen as a cold-blooded sex-feind. The truth was, of course, far less Lifetime-y. The story of Charity Lamb is one born of an all too familiar circumstance-- a woman trying desperately to survive her marriage to a violent man.

The Crime

It happened on a Saturday evening. Charity, her husband, and their children sat around the table for a dinner Charity had certainly spent some time preparing. At some point during the meal, Charity stood from the table and left the cabin. We cannot be sure if there was a reaction of any sort from the rest of the family, not until Charity returned just a moment later with an axe. She stepped up behind her husband and hit him as hard as she could in the back of his head not once but two times. After doing so, she and her eldest child, Mary Ann, who was seventeen at the time, fled. The remaining children watched in horror as their father fell to the floor, his body “scrambl[ing] about a little” before falling unconscious. The man did not die immediately; instead, he held on for a few days before dying.

What seemed to have precipitated this event was the affections Mary Ann felt for a man named Collins. Collins was said to have been a farmhand working for a family nearby. There is no record to confirm whether or not the feelings were reciprocated. Perhaps Mary Ann had not gotten a chance to truly express her feelings to the man before her father forbade her from being with him which subsequently led to the teenager asking her mother for help in writing a secret letter to the young man.

Nathaniel discovered the letter on his wife and accused her of having feelings for Collins herself. We cannot be sure whether or not she truly had feelings for the young man but we can make assumptions-- a case such as this makes a retelling without such assumptions practically impossible. It is unlikely that this woman with a group of children and nearing forty would have been pursuing a presumably penniless farmhand. What is far more believable is that Charity, a mother who knew very well how deeply her daughter’s feelings went, was doing her best to help. Regardless of what was the truth, Nathaniel was furious. He threatened Charity, threatened to take her children away, to murder her. Charity was quite obviously terrified but according to their children who testified at her trial, Nathaniel had frequently been violent with their mother. He’d knocked her to the ground, kicked her, forced her to work when she was sick. He was downright brutal with her for their entire marriage which leaves us to wonder-- what was it about this last threat that scared her so much? Charity was used to this violence so whatever he said to her, whatever he might have done was enough for her to legitimately believe her life was in jeopardy.

According to Charity, he’d threatened her just as he had many times before; however, this time he was serious. He told her that she would die before the end of the week and once she was gone he’d take their children far away, hurting them in the process. He told her that if she ran, he’d hunt her down and shoot her— it was known how good of a shot Nathaniel was as he was an avid, accomplished hunter.

The Trial

Charity and Mary Ann were arrested following the events of that morning. The community was outraged. They hated them, and saw them as monsters. Newspapers practically rewrote the events to match whatever story they believed would sell. They told salacious fable after salacious fable until Charity became the most hated woman in the Oregon territory.

Mary Ann went to trial before her mother and was acquitted. One can only imagine the relief Charity must have felt— this was her fight, certainly not something she wanted her daughter tangled up in anymore than she already was. Charity’s trial followed a few days later and a similar outcome was expected; however, she would not be so lucky.

A part of the blame can be put on the men who decided to defend her. They had her plead not guilty by reason of insanity, insisting that Charity was not mentally sound; therefore, she could not have known the consequences of her actions. They claimed that her husband’s actions had driven her to insanity. This proved to be the beginning of the end for her hopes of acquittal as anyone in the room could see that she was relatively competent. The judge, in a move that was questionable for someone who was supposed to remain impartial in such matters, sympathized with her. He instructed the jury to acquit if they truly believed her actions were done in self defense.

Despite the sympathies of the judge and the testimonies of the Lamb children confirming the abuses Charity claimed to experience, she was found guilty of murdering her husband.

Charity wept loudly as the verdict was read. This woman who had survived the Oregon Trail, multiple pregnancies, life on the frontier, and a violent husband was sentenced to prison where she would be subjected to hard labor. The officers had to take her infant from her arms, depositing the child into the arms of another.

There were no prisons for women in the Oregon territory; Charity was the first woman to be charged with such crimes in the area. The local prison where she was eventually sent had no provisions for her and she remained the only female prisoner for her entire stay. She did the warden’s laundry and other household tasks to fulfill her sentence of hard labor until she was transferred to Oregon Hospital for the Insane in 1862. She lived out the rest of her days in that hospital with a smile on her face and proclaiming her innocence.

What do you think about the trial of Charity Lamb? Let us know below.

Sources

Lansing, Ronald B. "The Tragedy of Charity Lamb, Oregon's First Convicted Murderess." Oregon Historical Quarterly 40 (Spring 2000)

“Charity Lamb.”, The Oregon Encyclopedia

https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/lamb_charity_1879_/#.Xukj7kXYrrc