In 1860 Western forces burned the Summer Palace, a wonderful and magnificent building to the northwest of Beijing, China. British and French troops pillaged the palace, and then burned it to the ground in a terrifying act during the Second Opium War. Here, Scarlett Zhu explains what happened and responses to the attack.

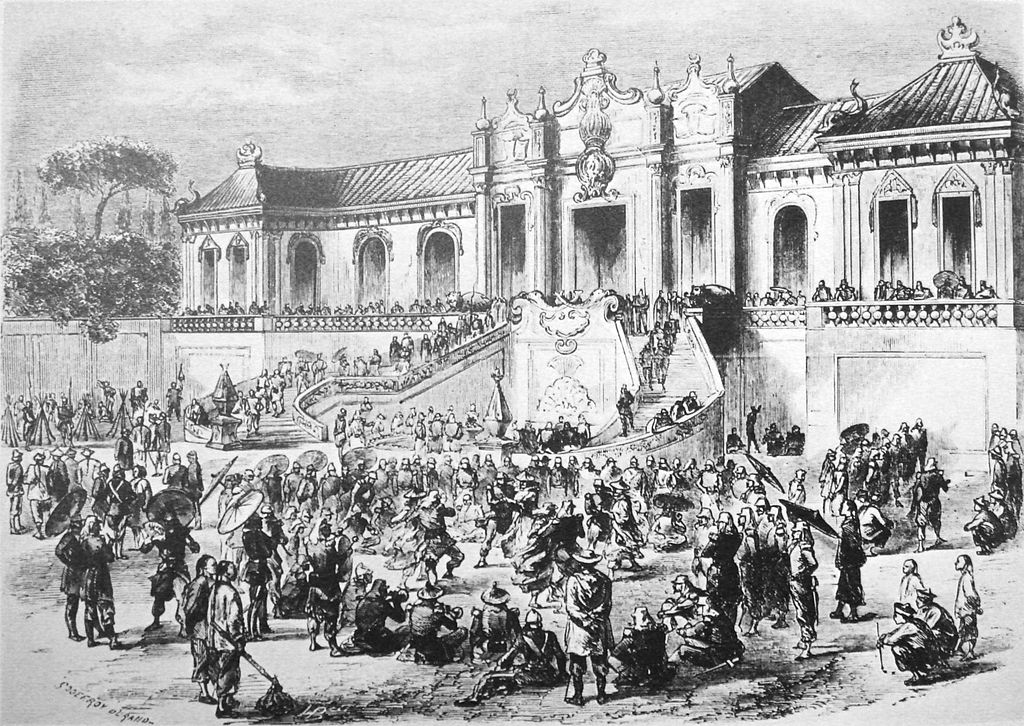

The looting of the Summer Palace by Anglo-French forces in 1860.

"We call ourselves civilized and them barbarians," wrote the outraged author, Victor Hugo. "Here is what Civilization has done to Barbarity."

One of the deepest, unhealed and entrenched historical wounds of China stems from the destruction of the country's most beautiful palace in 1860 - the burning of the Old Summer Palace by the British and French armies. As Charles George Gordon, a soldier of the force, wrote about his experience, one can "scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the places being burnt."

The palace that once boasted of possessing the most extensive and invaluable art collection of China, became a site of ruins within 3 days in the face of some 3,500 screaming soldiers and burning torches. Dense smoke and ashes eclipsed the sky, marble arches crumbled, and sacred texts were torn apart. At the heart of this merciless act stood Lord Elgin, the British High Commissioner to China, a man who preferred revenge and retaliation to peace talks and compromise. He was also a man highly sensitive to any injustices or humiliation suffered by his own country. Thus, the act was a response to the imprisonment and torture of the delegates sent for a negotiation on the Qing dynasty's surrender. However, as modern Chinese historians would argue, this was a far-from-satisfactory excuse to justify this performance of wickedness, as before the imprisonment took place, there had already been extensive looting by the French and British soldiers and the burning was only "the final blow".

The treasures of the Imperial Palace were irresistible and within the reach of the British and French. Officers and men seemed to have been seized with temporary insanity, said one witness; in body and soul they were absorbed in one pursuit: plunder. The British and the French helped themselves to all the porcelain, the silk and the ancient books - there were an estimated 1.5 million ancient Chinese relics taken away. The extent of this rampant abuse was highlighted even more by the burning of the Emperor's courtiers, eunuch servants and maids - many estimates place the death toll in the hundreds. This atrocious indifference towards human life inflamed international opposition, notably illustrated by Hugo's radiant criticisms.

The response to the attack

But there was no significant resistance to the looting, even though many Qing soldiers were in the vicinity - perhaps they had already anticipated the reality of colonial oppression or did not bother themselves with the painful loss of the often-distant imperial family. But the Emperor, XianFeng, was not an unreceptive spectator; in fact, he was said to have vomited blood upon hearing the news.

However, there was evidence to suggest that some soldiers did feel that this was "a wretchedly demoralizing work for an army". As James M'Ghee, chaplain to the British forces, writes in his narrative, he shall "ever regret the stern but just necessity which laid them in ashes". He later acknowledged that it was "a sacrifice of all that was most ancient and most beautiful”, yet he could not tear himself away from the palace's vanished glory. Historian Greg M. Thomas went so far as to argue that the French Ambassador and generals refused to participate this destruction as it "exceeded the military aims of their mission", and would be an irreparable damage to an important cultural monument.

Nowadays, what is left of the palace are the gigantic marble and stone blocks, which used to be backdrops of the European-style fountains situated in the distant corner of the Imperial gardens for entertaining the Emperor, since those made out of timber and tile did not survive the fires. The remains acted as a somber reminder of the West's ransack and the East's "century of humiliation".

This is more than a story of patriotism, nationalism and universal discontent. History used to teach us that patriotism isn't history, but rather propaganda in disguise. Yet how could one ignore and omit a historical event so demoralizing and compelling on its own, that it is no longer a matter of morality and dignity, but a matter of seeking the truth, tracing the past and its inseparable link with the present? When considering the savage and blatant destruction of the Old Summer Palace, along with the unspoken hatred of the humiliated and the suppressed, it seems therefore appropriate to end with the cries of the enraged Chinese commoners as they witnessed the worst of mankind's atrocities: “Kill the foreign devils! Kill the foreign devils!”

Did you find this article of interest? If so, tell the world – tweet about it, like it, or share it by clicking on one of the buttons below.

Bibliography

1. Hugo, Victor. The sack of the summer palace, November 1985

2. Bowlby, Chris. "The palace of shame that makes China angry"

3. M'Ghee, Robert. How we got to Pekin: A Narrative of the Campaign in China of 1860, pp. 202-216, 1862

4. "The Burning of the Yuan Ming Yuan: 150 Years Later", http://granitestudio.org/2010/10/24/the-burning-of-the-yuanmingyuan-150-years-later

5. "Fine China, but at what cost?”, http://thepolitic.org/fine-china-but-at-what-cost/