Aaron Burr's life has always tangled itself in controversy. From killing the first Secretary of the Treasury and key figure in the Federalist Party, Alexander Hamilton, to being the defendant of the United States' first treason case, Aaron Burr was well known for a lot of questionable decisions and bad luck. However, none of his decisions were as objectively manipulative, callous, and greedy as purposefully letting New York City suffer with tainted water for the sake of building a bank. Haley Booker-Lauridson explains.

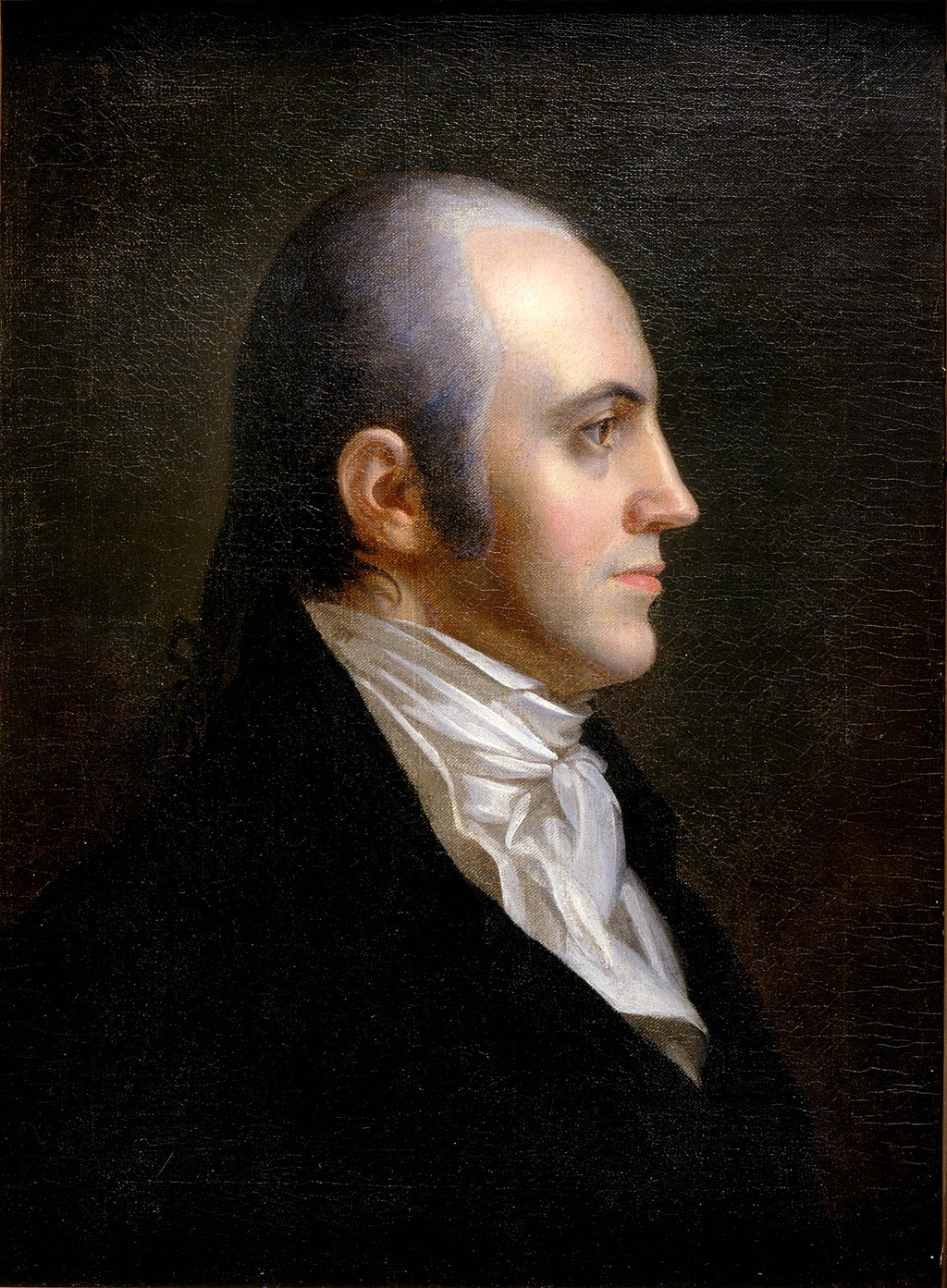

An early 19th century painting of Aaron Burr.

The New York Water System

Back when New York was New Amsterdam, the water sources were from nearby ponds, streams, and wells, and continued that way for many years. Without a waterworks system, the city's waste ran into the same water it drank from, and distributing drinking water to various areas of the city proved difficult. This troubled Christopher Colles, an Irish engineer and inventor who emigrated to Philadelphia in 1771, just four short years before the Revolution.

In 1775, he began organizing a project he proposed, constructing a water distribution system in the heart of New York. This system used a steam engine pump to extract water from various wells into a reservoir, which would then distribute the water throughout the city in pipes. However, the Revolutionary War came to the city a year later and the project had to be put on hold, and the British soldiers soon destroyed what was left of the fledgling water system.

Though he made several attempts at creating various waterways and different systems in the newly formed United States, none of his projects came to fruition. The water in New York was left in a state of rapid pollution. Without a way to draw clean water, the citizens of New York City drank water steeped in animal, human, and industrial waste. Water distribution was another problem; fires could not consistently be quelled without a distribution system that could quickly get the water to the flames.

With a population of 60,515 people in the city, the waters became increasingly dangerous. By 1798, up to 2,000 people died of yellow fever, which doctors attributed to the filthy water people were drinking. By that time, New Yorkers desperately needed a plan to bring clean water to the city.

"Pure and Wholesome Water"

Nearly 24 years after Colles proposed a water distribution system, a bill to secure water from the Bronx River was drafted and sent to the New York State Assembly in 1799.

Aaron Burr, State Assemblyman and Democratic-Republican, worked to convince the Assembly to let the city and state use a private company for their water. While Democratic-Republicans were the main supporters of the bill, they received help from an unlikely ally, Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton campaigned for the Federalist Assemblymen to reach across the aisle. As New York had become his home when he emigrated to America in 1772, it is easy to see why he might want to turn the water bill into a bipartisan decision. The water was terribly polluted and toxic, and Aaron Burr had partnered with him on several occasions, including working as defense attorneys in the first murder trial in the United States. Having trusted Burr and having believed in the cause for a waterworks system, Hamilton convinced his fellow Federalists to back the creation of the Manhattan Water Company.

What Hamilton, and many Assemblymen, did not know was that Burr, just before submitting the bill for its final approval, slipped in a clause allowing the company to use "surplus capital" however it chose, as long as it followed state and federal law. The bill passed through with this clause on April 2, 1799, and the Manhattan Company was created to supply New York with "pure and wholesome water."

This small, unassuming clause transformed what was intended to be a water system for New York into a bank. Burr intended to establish a bank all along. He and other Democratic-Republicans inherently distrusted the First Bank of the United States and its branch in New York, as it was linked with Federalist politics. They feared discrimination in receiving credit and loans, and also desired the power to control campaign finance with their own bank. They wanted to establish a bank manned by their own political party, and schemed to use the city's water crisis to manufacture one right under the Federalists' noses.

The Manhattan Water Company's Legacy

By September 1, 1799, the Bank of the Manhattan Company opened, eventually becoming the oldest branch of JP Morgan Chase, and remains a financial institution today.

While the Manhattan Water Company was ostensibly a front for a bank, it did provide the city's first waterworks system. Shoddily put together, it constructed a cheap, crude network of wooden water mains throughout the city, by coring out yellow pine logs for pipes and fastening them together with iron bands.

The system was sub-par at best. It froze during the winter and the tree roots easily pierced through the log pipes, causing terrible back-ups. Even when the system worked, the people suffered through pitifully low water pressure. And, despite having permission to get clean water that ran down the Bronx River, Burr chose to source water from the polluted sources the city tried to get away from.

The Manhattan Water Company continued laying wooden pipes in the 1820s, even though other U.S. cities began using iron clad pipes. It remained the only drinking water supplier until 1842, leaving people with unreliable and bad water for over forty years.

As the water system floundered and the bank flourished, Aaron Burr experienced very little but misfortune from then on. Hamilton made it his duty to keep Burr out of influential public offices, famously campaigning against Burr during the 1800 election, and later in New York's gubernatorial race in 1804. Hamilton often negatively featured Burr in his newspaper, the New York Post. He likely would have continued had he not been fatally wounded in a duel with the man in July of 1804. Burr faced political exile that solidified when he was tried for treason in 1807, eventually fleeing to Europe for several years before returning to the U.S. and living as a perpetual debtor until his death in 1836.

What do you think of Aaron Burr? Let us know below.

References

Beatrice G. Reubens, “Burr, Hamilton and the Manhattan Company. Part I: Gaining the Charter,” Political Science Quarterly, LXXII (December, 1957), 578–607.

Beatrice G. Reubens, “Burr, Hamilton and the Manhattan Company. Part II: Launching a Bank,” Political Science Quarterly, LXXIII (March, 1958), 100–25.

“New York City (NYC) Yellow Fever Epidemic - 1795 to 1804” http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/disasters/yellow_fever.html

"The History of the Water Mains in New York City" https://www1.nyc.gov/html/dep/html/drinking_water/wood_water_pipes_history.shtml.

New York Laws, 22nd Sess., Ch. LXXXIV.