One man links two of the most notorious crimes of the nineteenth century – an Irish American by the name of Francis Tumblety. It stretches credulity but this individual, arrested in 1865, as a suspected member of the gang behind the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, was also detained by Scotland Yard in 1888 over the Jack the Ripper case.

Tony McMahon, author of a related book (Amazon US | Amazon UK), explains.

Francis Tumblety in a military uniform.

If the story rested on the bizarre coincidence of the arrests in 1865 and 1888, that would be compelling enough. But during my research, I encountered an extraordinary figure whose life consisted of a series of crises and scandals. It included two manslaughter cases; violent assaults; arrests for gross indecency; and accusations of business fraud. Then add to that being arrested as a suspected co-conspirator in the Lincoln assassination and Scotland Yard drawing up charges in relation to the Jack the Ripper case.

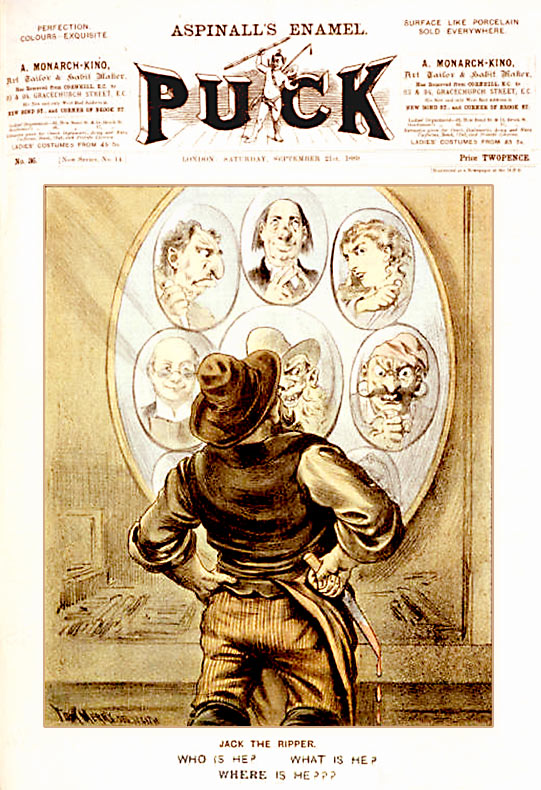

Even after the 1888 arrest over the Ripper murders - when Tumblety jumped bail and escaped to New York - he was soon in court for striking a young man while Manhattan later shuddered in horror at news of a copycat Ripper killing in a hotel. New Yorkers were convinced the Whitechapel murderer was in their midst and the newspapers pointed an accusing finger at Tumblety.

Tumblety did not operate in the shadows. Far from it. Styling himself the Indian Herb Doctor, he was a high-profile medicine man skillfully using the emerging mass circulation newspapers to transform himself into a nineteenth century celebrity, known throughout north America (Canada and the United States). In fact, his celebrity, and the networks he developed in high society, played a key role in protecting him from imprisonment on multiple occasions. It may also explain why he was not extradited from the United States to face the Ripper charges in London after absconding.

Tumblety’s sexuality

As an LGBT historian, I am fascinated by Tumblety’s very open homosexuality. The term was yet to be popularized in the mid-nineteenth century but nobody needed sodomy to be defined. Gay men were recognized in clubs, theatres, and taverns. Journalists commented on the doctor's nocturnal cruising and very literal clashes with younger men he picked up, then fell out with bitterly. He supplied great copy for the gossip columns of the newspapers given his repeat brushes with the police and courts. For decades he was tailed by the Pinkerton detective agency who seemed obsessed by the doctor’s man problems.

While he has been recognized as a Ripper suspect since his arrest, Tumblety’s sexuality has often been skirted around, maybe to save the blushes of some Ripperologists. Also because it raises awkward questions about his motives in the Ripper murders, which I set out to tackle in the book. To understand the kind of life he led and how he came to be implicated in these two enormous crimes, it’s impossible not to put his homosexuality center stage.

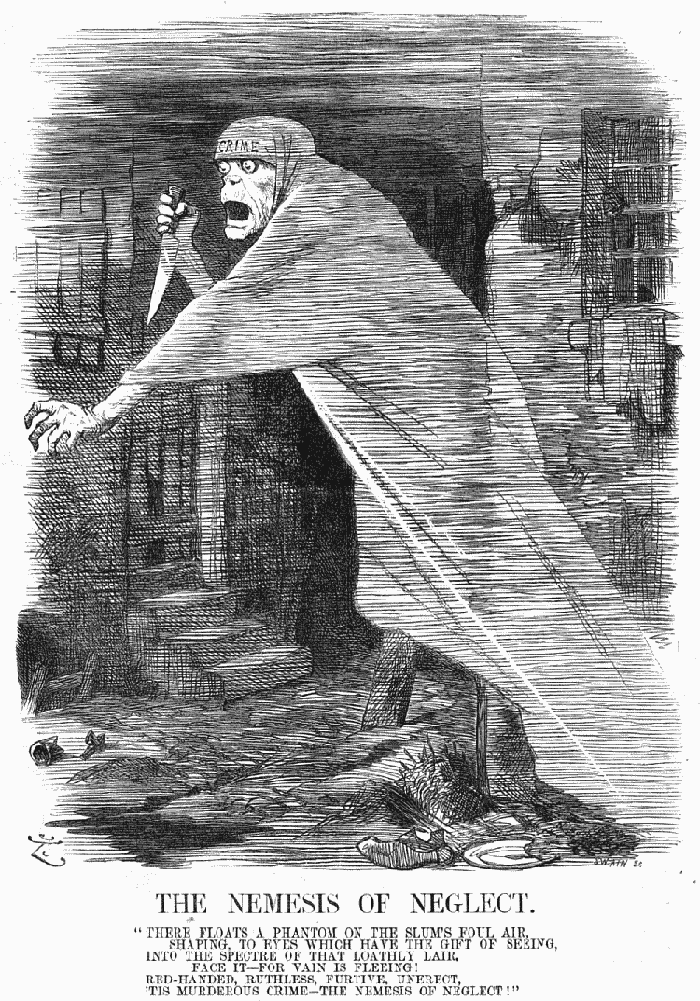

Tumblety claimed to be disinterested in the opposite sex after marrying a woman he then discovered was a prostitute. I suspect this story, told by Tumblety in his multi-edition slim autobiography, may not be true. It offered a cover for his same sex preference coupled with a violent misogyny noted by the American police and shared by them with Scotland Yard. The London police were further convinced he was Jack the Ripper after reports in the American press that Tumblety owned a grotesque collection of uteruses in glass jars which he displayed at his all-male dinner parties. The Ripper’s second victim, Annie Chapman, was missing her uterus when her body was discovered.

America

This intriguing figure began his life in Dublin but like many Irish at the time, including many of my ancestors, he boarded a ship for a new life in America. His family set up home in Rochester, New York, and the Irish teenager lived in miserable poverty. But he was growing up in a country experiencing rapid growth where hucksters and opportunists changed their backstory, adopted a glamorous persona, and fleeced the vulnerable, making considerable fortunes. This was capitalism at its most unregulated and freewheeling.

Clearly not without talent, Tumblety set himself up as a completely unqualified doctor with a flamboyant persona. To promote his dubious medical business, he processed down main street on a circus horse with a plumed helmet and assistant dressed as a native American handing out leaflets. With bombastic language, he declared war on mainstream physicians and claimed his herbal cures could tackle everything from pimples to cancer.

The association with Lincoln began with an astonishing appearance on horseback behind Lincoln’s carriage when the newly elected president processed through New York, having just been elected president in early 1861. Journalists were aghast at this unlikely vision, as the herb doctor was embroiled at that moment in a rather sordid legal case involving one of his young male assistants. Yet Tumblety ignored the brouhaha and set out to ingratiate himself with the president by moving to Washington DC, attending Lincoln’s public appearances.

However, he seems to have been playing a double game. I’ve uncovered evidence linking Tumblety to at least two members of the gang that plotted Lincoln’s assassination and a newspaper article from 1914 that proves he knew the man who fired the fatal bullet: John Wilkes Booth. Little wonder that Tumblety was arrested and held at the Old Capitol Prison in the aftermath of the presidential slaying. Somehow, though, he was able to walk out of jail a free man.

After Lincoln

The quarter of a century between the Lincoln killing and the Ripper murders saw Tumblety flitting between America and Europe. The police and Pinkerton agency continuing to keep tabs on this strange character. I believe he contracted syphilis at some point and that the condition impacted both his physical and mental health as we approach 1888. The alleged manslaughter of a patient in Liverpool led to no conviction, possibly the result of an out-of-court settlement. Then the herb doctor was arrested over gross indecency with four men. While he was being held, Scotland Yard changed tack, realizing he was Jack the Ripper.

Without giving too much away, he ends up back in the United States and it’s his last years, neglected up until now, that are very revelatory. There is clear proof that Tumblety had cultivated networks in the Irish American diaspora and what passed for a gay community. In two cases, respected political figures rescued him from criminal convictions – but for what reason?

Conclusion

American journalists had no doubt that Tumblety was the notorious serial killer who had struck terror into the streets of Whitechapel. I share some ideas, based on his life experience and character, that explain why a gay man would have committed such heinous acts. His sexuality does not rule him out at all. Reporters speculated on other crimes that he may have been linked to and the possibility that one of his “valets” – young male employees – could have helped him on his murder spree.

To me, Tumblety presents a far more intriguing prospect as Jack the Ripper than a rogue member of the Royal Family or a conspiracy by Freemasons. He was a rags to riches story that guides us through Civil War America, the Gilded Age, and on to the streets of Victorian London. His life was turbulent, violent, and scandalous. What he did was unforgivable and sheds so much light on the sexual politics, media landscape, and precarious existence that millions of people led during this period.