How It All Began

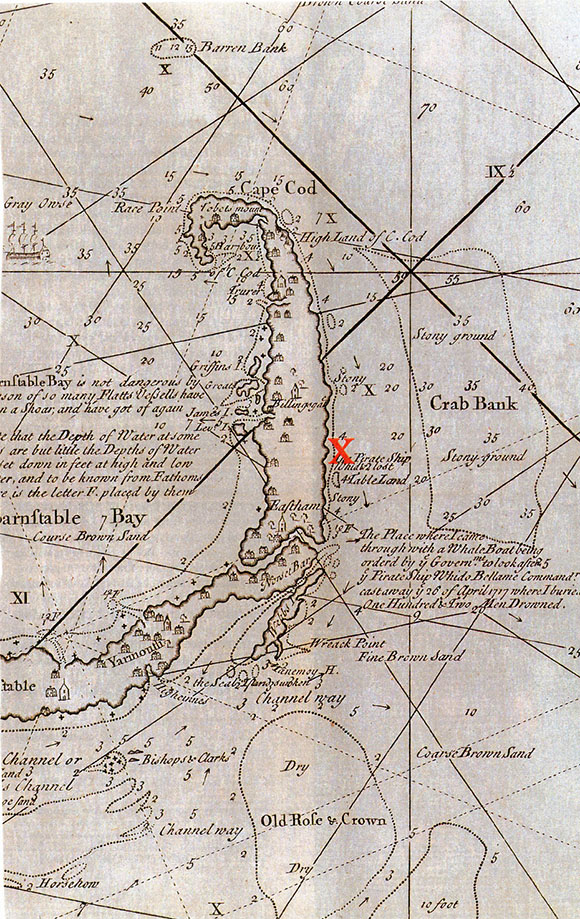

Bellamy had been in command of the Whydah since March. He had started out as a treasure hunter in Florida, diving for sunken Spanish treasure. He acquired a couple of periaguas (canoes) and plundered a few ships, then hooked up with Benjamin Hornigold, who provided him an opportunity to learn the craft of high seas piracy. When the crew rebelled because Hornigold wouldn’t attack English ships, Bellamy was elected captain, and his career took off. By the time the Whydah and the majority of her crew were lost on a shipwreck off Cape Cod in April of 1717, he had plundered about 50 ships and collected tens of thousands of dollars in treasure and coins.

The pirates sailed northward along the eastern seaboard of the American colonies that day reportedly headed for Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Some accounts say that Bellamy wanted to reconnect with his lover, Maria Hallet. Others say he was headed towards a tavern he knew of in the area where he could trade some of their goods for cash and other necessities. Around 4 to 6 in the morning, between Nantucket Shoals and St Georges banks, they crossed paths with a ship called the Mary Anne. Ordering the captain of the pink to strike her colors, Bellamy sent seven members of his crew over to her in a boat to take charge of her as a prize ship.[i]

The Day of the Wreck

Of the seven men sent aboard the Mary Anne, Hendrik Quintor, Peter Cornelius Hoof, John Shuan, John Brown, Thomas South, Thomas Baker and Simon Van Vorst, Baker came aboard with his sword drawn, while only South and Shuan came aboard unarmed. The armaments of choice were muskets, pistols, and cutlasses. The captain of the Mary Anne, Crumpstey, was ordered to go aboard the Whydah with his ship’s papers and five members of his crew. Once on board the Whydah the crew of the Mary Anne were promptly held as prisoners. A perusal of her papers revealed that she was carrying a cargo of 7,000 gallons of Madeira wine.

Back aboard the Mary Anne, the prize crew quickly discovered that a heavy cable was blocking access to the hold. Letting it go for the time being, they plundered the crew quarters, taking clothes and some bottles of wine that they found in the Captain’s cabin. Hearing of the discovery, some of the crew of the Whydah rowed over to get a couple of the bottles to take back and share amongst their crewmates.

While this was going on, some of the prize crew finally managed to move the cable blocking the hold and they were able to get at the barrels of Madeira. Van Vorst told two of the crewmen of the Mary Anne, Thomas FitzGyrald and Alexander Mackconachy, “That if he would not find liquor he would break his neck.”[ii] The pirates began to indulge.

Ordered by Bellamy to follow the Whydah, the pirates forced the crew of the Mary Anne to alternate taking turns at the wheel with them. Things were going fine until about 4 in the afternoon, when fog began to cover the sea. Bellamy then gave new orders to steer to the North, and put a light on the stern of the Whydah for the prize crew to follow. They also kept company with a sloop called the Fisher which was out of Virginia and that Bellamy had captured that same day.

But the prize crew had been partaking of the captured wine since morning, and began to fall behind. When Bellamy ordered them to keep up, Brown swore “That he would carry sail till she carried her masts away.”[iii] Baker told the remaining crewmen of the Mary Anne that they had a commission from King George, upon which Van Vorst answered, “We will stretch it to the Worlds end.”[iv]

Throughout the day the prize crew from the Whydah took charge of the Mary Anne, ordering her remaining crewmembers to do such chores as reefing the topsail. But, when they began to realize how leaky the Mary Anne was, everyone took turns manning the pumps.

About ten o’clock in the evening, the thick fog became a thunderstorm. “An Arctic storm from Canada was driving into the warm air that had swept up the coast from the Caribbean. The last gasp of a frigid New England winter, the cold front was about to combine with the warm front in one of the worst storms ever to hit the Cape.”[v] “According to eyewitness reports, gusts topped 70 miles [113 kilometers] an hour and the seas rose to 30 feet [9 meters].”[vi] They had long since lost sight of the Whydah. No one on board the Mary Anne could see adequately, and thus they failed to discover how close they were to the shore until they were amongst the breakers. By then it was too late, and the Mary Anne ran ashore. Upon realizing their plight, one of the prize crew cried out, saying “For God’s sake let us go down into the hold and die together!”[vii]

Everyone stayed in the Mary Anne’s hold for the rest of the night, at one point one of the prize crew asking FitzGyrald to read from the Common-Prayer Book, which he did for about an hour. When the ship ran onto shore, Baker went out and cut down the fore and mizzen masts in an effort to keep the ship from further peril.

The Next Morning

When they woke in the morning they found that one side of the ship had beached on dry ground and they could walk out onto what proved to be a small island. Shuan and Quintor broke into a crewman’s chest and took out some sweetmeats and other items to eat, washing it all down with more wine. Brown declared himself to be the captain and the other members of the prize crew to be his men. There was talk amongst them of trying to reach Rhode Island, at that time a haven for pirates.

Around ten o-clock that morning local residents John Cole and William Smith passed by and saw the men’s plight. They rowed over to the little island in a canoe and took them over to the mainland. While resting at Cole’s house, Mackconachy found the courage to speak up and reveal that these men were pirates and members of Bellamy’s company. Now they had no choice but to flee. They made a fateful decision to stop and refresh themselves at a tavern in Eastham, Massachusetts. There they were apprehended by Justice Doan. They spent the night in Barnstable Gaol in Eastham. The next day they were put on horseback and taken to Boston to await their trial.

During their journey to Boston the pirates were joined by two of their crewmates from the Whydah, Thomas Davis and John Julian. From Davis and Julian they learned that the Whydah had been lost in the storm after they lost track of her the night before and that they were the only two survivors. The men must have been despondent over the loss of their friends and their treasure.

Imprisoned

From the end of April until October the pirates were confined in Boston’s hot, foul jail. It is during this period of time that John Julian disappears from official records. Depending on what source you read, he either died in jail, escaped, or was sold into slavery. Some believe he may have been the Julian the Indian who is mentioned in a 1733 paragraph in The Weekly Rehearsal, a Boston newspaper, describing a slave who killed a bounty hunter while trying to escape who is going to be executed the next day.

To break the monotony of their confinement, the pirates were ministered to by the Reverend Cotton Mather, of Salem witch trial fame. The pirates from the Mary Anne were one of at least three groups of pirates he would minister to during his lifetime.[viii] Mather considered it a personal mission to persuade such men to repent. At one point he felt so good about the work he was doing with one of them that he noted in his diary, “Obtain a reprieve and, if it may be, a pardon for one [of the] Pyrates, who is not only more penitent, but also more innocent than the rest.”[ix] Unfortunately, inquiries into historical records in Boston failed to unearth any evidence that Mather ever took any official steps towards obtaining an actual pardon, nor for which of the pirates he was referring to.

Unknown to the pirates, while they languished in prison, Blackbeard was making plans to come to Boston to attempt a rescue. He set out from the West Indies, (or never left the harbor, depending on which source you read), but had not gotten very far when he learned that the authorities in Boston had ordered a blockade of the harbor with a man-of-war and several other ships. After the six pirates were hanged, he took out his vengeance on several ships from Boston, burning them to the waterline, cargo and all, including a ship called the Protestant Caesar, in the Bay of Honduras.

Something else the pirates didn’t know about was that on September 5, 1717, King George I issued a royal proclamation for the suppression of piracy that included a pardon. The pardon read, in part:

…we do hereby promise, and declare, that in Case any of the said Pyrates, shall, on or before the Fifth Day of September, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Eighteen, surrender him or themselves, to one of our Principal Secretaries of State in Great Britain or Ireland, or to any Governor or Deputy Governor of any of our Plantations beyond the Seas, every such Pirate and Pirates so surrendering him, or themselves, as foresaid, shall have our gracious Pardon…[x]

This date is important because there is some debate as to when exactly the authorities in Boston became aware of the pardon’s existence. There is some speculation that they knew the arrival of the pardon was imminent and thus hastened the trial and execution. On December 9, 1717, the Boston News-Letter published the proclamation.

Pre-Trial Interrogation

Each of the pirates was interrogated before the trial. Unfortunately the name or position of the person or persons who conducted the interviews is not mentioned, and the men’s answers are written in paragraph form, rather than in the question and answer format we’re used to seeing in modern court transcripts.

John Brown of Jamaica spoke at length about how he was originally a captive of Louis Labous’ ship. After four months he requested to transfer to Bellamy’s ship in hopes of escaping more easily.[xi] Brown tells of the movement of the pirates during the past year, including some of the places they visited and ships they plundered. He also told of how there were 50 forced men and that the pirates kept a watchful eye over them. The forced men’s names were entered onto the watch bill (duty roster) and they had to perform ship’s duties the same as the pirates.

Thomas Baker, from Flushing, Holland, said that he was never sworn as the rest of the men were, and that married men were sent away rather than being forced. When he pleaded with Bellamy to be released, Bellamy threatened to maroon him “if he would not be easy.”[xii] The pirates had about 20,000 to 30,000 pounds aboard, which he said the Quarter Master declared any man could have some if he wanted. Baker described how the pirates flew a black flag with a Death’s Head and crossed bones on it when they attacked ships.

Thomas Davis of Wales said he was by trade a Shipwright and was also originally a captive of Labous. Davis gives the number of forced men as being one hundred and thirty.

Peter Cornelius Hoof of Sweden said that about three weeks after he was taken captive there was a disagreement amongst the pirates about what ships of what nations to attack. As a result of the disagreement, Benjamin Hornigold and a few of his loyal men departed the company. Hoof stated that “the Money taken in the Whido, which was reported to Amount to 20,000 to 30,000 Pounds, was counted over in the Cabin, and put up in bags, Fifty Pounds to every Man’s share, there being 180 Men on Board… Their Money was kept in Chests between Decks without any guard, but none was to take any without the Quarter Master’s leave.”[xiii]

John Shuan of Nantes, France, said that he was taken captive by Bellamy while coming from Jamaica. Shuan said he also was never sworn.

Simon Van Vorst of New York was another man who was originally held captive by Labous and later transferred to Bellamy. Bellamy told him he couldn’t leave the company until they had more volunteers or he would maroon him.

Hendrick Quintor of Amsterdam was originally a captive of Labous. He said that he and the other six men who were sent on board the Mary Anne were forced men.

Thomas South of Boston said that the pirates forced the unmarried men from his ship to stay on board Bellamy’s vessel. The pirates brought arms to him and threatened him when he wouldn’t take any. He told a member of the Mary Anne’s crew that he would run away from the pirates if the opportunity arose.

Preparing for the Trial

Finally on October 18, 1717, the pirates were brought to the State House in Boston for trial. On this first day the indictments “for Crimes of Piracy, Robbery & Felony committed on the high Seas”[xiv] against the pirates were read and included several articles: First, that the pirates “without lawful Cause or Warrant, in Hostle manner with Force & Arms, Piratically & Feloniously did Surprize, Assault, Invade, and Enter… the Mary Anne of Dublin…” Second, they did “Piratically & Feloniously seize and imprison Andrew Crumpstey, Master thereof….” Third, they did “Piratically & Feloniously Imbezil, Spoil and Rob the cargoe of said vessel….” And fourth, they “were powered and subdued the said Master and his Crew, and made themselves Masters of the said Vessel… di then and there Piratically & Feloniously Steer and Direct their course after the above-named Piratical Ship, the Whido, intending to joyn and accompany the same, and thereby, to enable themselves better to pursue and accomplish their Execreble designs to oppress the Innocent, and cover the Seas with Depredations and Robberies.”[xv]

After the indictments were read, Van Vorst requested, and the pirates were granted, council, a move that was not generally common in trials at that time. Robert Auchmuty argued that the court did not have jurisdiction because the commission of the late Queen Anne had ended with her death. The court countered that the proclamations of King George were sufficient jurisdiction. He also asked that Thomas Davis, the Whydah’s carpenter, be brought in to give evidence on the pirate’s behalf. The motion was rejected because Davis was also in prison for the same offense and was waiting to be tried separately. When his motion to have Davis called as a witness for the pirates was denied, Auchmuty resigned and left the court.

The pirates all held up their hands and pleaded not guilty except Shuan, who managed to make known to the court that he didn’t understand the proceedings because he didn’t speak English. The court then swore in Mr. Peter Lucy to translate for Shuan at which point Shuan also pleaded not guilty. The prisoners were provided copies of the indictment along with the names of the King’s witnesses and sent back to Gaol until the court convened again.

The Trial Begins

The court reconvened on October 22, 1717. The pirates, of unknown education and level of literacy and only one attorney, faced a powerhouse court consisting of:

His Excellency Samuel Shute, Esq., Governour, Vice Admiral & President;

The Honourable William Dummer, Esq., Lieutenant Governour;

The Honourable Elisha Hutchinson, Penn Townsend, Andrew Belcher, John Cushing, Nathaniel Norden, John Wheelwright, Benjamin Lynde, Thomas Hutchinson, and Thomas Fitch, Esqrs., of His Majesty’s Council for this Province;

John Meinzies Esq., Judge of the Vice Admiralty;

Capt. Thomas Smart Commander of His Majesty’s Ship of War the Squirrel, and John Jekyll Esq., Collector of the Plantation Duties.[xvi]

An interesting part of reading the trial transcript is that the prosecutor and witnesses have statements of one or more paragraphs, while the pirates’ statements are only a sentence or two, an inaccuracy in transcribing the actual trial proceedings that would be shocking today.

Then the Advocate General gave a long speech addressing the crimes of the pirates. His speech is written out over three pages in small letters. One of his first arguments is that since most governments have declared pirates to be enemies of mankind, “therefore he can claim the Protection of no Prince, the privilege of no Country, the benefits of no Law.”[xvii] He describes how piracy is a more heinous crime than many because since it is conducted on the high seas, its victims often have no chance for rescue or escape, and are left helpless after the crime.

Then the witnesses were called. Thomas FitzGyrald, late mate of the Mary Anne, testified that when Baker came on board he approached Captain Crumpstey with his sword drawn and ordered him to board the Whydah with his papers and five of his hands. That action left himself, Alexander Mackonachy, and James Dunavan behind on the Mary Anne.

FitzGyrald said that he was told by Van Vorst that if they didn’t find liquor he would break his neck.

He said Baker bragged that they had a commission from King George, and Van Vorst then declared that they would “stretch it to the World’s End.”[xviii]

He then told of how at one point in the evening Baker threatened to shoot Mackonachy through the head because he had steered to windward of their course, and that shooting him was no more to him than shooting a dog.

Other witnesses were brought in to testify that they had been held by either Bellamy or Labous at one point, and that while they were imprisoned Brown was very active among them and that Shuan had declared to all that “he was now a pirate” willingly climbed and unrigged the main top-mast in response to an order by the pirates.[xix]

When the witnesses were done, the pirates were given an opportunity to speak for themselves. Each one reiterated that they were forced men under threat of death or marooning. Van Vorst added that the Mate of the Mary Anne revealed that he was inclined to be a pirate himself, so he declined to reveal to him that he actually wanted to try and escape. [xx]

Baker declared that he tried once to escape at Spanish Town, but Bellamy “sent the Governour word that they would burn & destroy the Town, if the said Baker, and those who concealed themselves with him were not delivered up. And afterwards he would have made his escape at Crab Island, but was hindered by four of Capt. Bellamy’s Company.”[xxi]

The Verdict

Ultimately, the court found it not credible that Bellamy and Labous would force men into piracy. All of them were found guilty except Thomas South. South fell on his knees and thanked the court. He was allowed to leave.

Then the court told the pirates that they would be taken to be hanged by the neck until dead. On November 15, 1717, the remaining six pirates were escorted to Charlestown Ferry for the hanging.

Mather walks with the Pirates

The afternoon of the execution, as the pirates were led from the jail through town to a canoe at the harbor, they were accompanied by Rev. Mather. Mather took time to speak with each of them as they walked. It must be noted that Mather wrote down from memory what he spoke to each of them about and their responses after the fact. Each man repented, but that of course did not save them from the hangman’s noose.

Van Vorst reiterated that they were all forced men, and that his biggest regret was “my Undutifulness unto my Parents; And my Profanation of the Sabbath.”[xxii]

Hoof declared that “my Death this Afternoon is nothing ‘tis nothing; ‘Tis the wrath of a terrible GOD after Death abiding on me, which is all that I am afraid of.”[xxiii]

Quintor told Mather “’Tis a Dark Time with me.”[xxiv]

When they reached the site of their execution, they heard a prayer given by the Minister of the city. Then they led onto the scaffold, at which point Baker and Hoof were said to appear to be “very distinguishingly Penitent.”[xxv] Brown, however, was said to have broken out in a fury, using language he had become accustomed to in the company of the pirates. He then read some prayers from a book he had been carrying, and gave a short speech advising sailors to “beware of all wicked Living, such as his own had been; especially to beware of falling into the hands of the Pirates: But if they did, and were forced to join with them, then, to have a care whom they Kept, and whom they let go and what Countries they come into.”[xxvi]

The others said little except for Van Vorst, who along with Baker sang a Dutch psalm, and advised youngsters to “Lead a Life of Religion, and keep the Sabbath, and carry it well to their Parents.”[xxvii]

The Execution

In 1717 hangings were not like you see in Wild West movies where the noose is tied around the neck, a horse or wagon is kicked out from underneath the condemned, his neck snaps from the force of the drop and, in a couple of minutes, he is dead. Hanging at this time was done by a method called the short drop. The noose was around the neck, but the body was only dropped a short distance, not enough to break the neck. What killed the person was the slow movement of the noose against the larynx, causing a prolonged, torturous death by slow asphyxiation. The entire process takes about fifteen to twenty minutes, during which time the body naturally convulses as the person chokes and gags while struggling for breath.

Hangings in this day were a public event, attended by hordes of people, who jeered and taunted the victims. Even children were brought along to watch the victims choke to death.

No death certificate exists for any of the pirates. As a deterrent to piracy, pirates’ bodies would be covered in tar and then caged in iron gibbets that were hanged from a scaffold in full view of the harbor. The tar was supposed to slow down the deterioration of the body. They would then be left there to rot, sometimes for years as a warning to sailors not to take up the profession of piracy.

Did you find this article intriguing? If so, share it, tweet about it, or like it by clicking on one of the buttons below.

[i] Pirate lingo for a ship that the pirates captured with the intention of plundering it for whatever goods (and sometimes even members of the crew) might be aboard and be of value or use to them.

[ii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 304.

[iii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 303.

[iv] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 304.

[v] “Technically known as an occluded front, the warm and moist tropical is driven for miles upward where it cools and falls at a very high speed, producing high winds, heavy rain, and severe lightning.” Clifford, Barry with Paul Perry. Expedition Whydah: The Story of the World’s First Excavation of a Pirate Treasure Ship and the Man Who Found Her, Cliff Street Books, 1999, p 262.

[vi] Donovan, Webster. “Pirates of the Whydah,” National Geographic Magazine (May 1999).

[vii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 304.

[viii] Vallar, Cindy. “Cotton Mather: Preacher to the Pirates,” in the online magazine Pirates and Privateers, October/November 2008 and January/February 2009. www.cindyvallar.com/mather.html. Other pirates he administered to included John Quelch in 1704 and William Fly in 1726.

[ix] Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down. Harcourt, 2007, p 227.

[x] Lee, Robert E. Blackbeard the Pirate: A Reappraisal of His Life and Times. John F Blair, publisher, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, 2006, p 243.

[xi] Louis Labous, or Olivier Levasseur, was a French pirate who sailed in consort with Bellamy from about mid-1716 until about January of 1717.

[xii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 318.

[xiii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 318 – 319.

[xiv] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p 296 – 297.

[xv] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p 296 – 297.

[xvi] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p 299.

[xvii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 300.

[xviii] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 303.

[xix] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 305.

[xx] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 306.

[xxi] “The Trials of Eight Persons Indited For Piracy” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering & Chatto, 2007, p. 306.

[xxii] Mather, Cotton. “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering and Chatto, 2007, p. 135.

[xxiii] Mather, Cotton. “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering and Chatto, 2007, p. 139.

[xxiv] Mather, Cotton. “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering and Chatto, 2007, p. 140.

[xxv] Mather, Cotton. “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering and Chatto, 2007, p 143.

[xxvi] Mather, Cotton. “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering and Chatto, 2007, p 143.

[xxvii] Mather, Cotton. “Instructions to the Living, from the Condition of the Dead” in British Piracy in the Golden Age, edited by Joel H. Baer, Pickering and Chatto, 2007, p 144.