Spying and espionage has been a part of war for centuries and the American Civil War (1861-65) was no exception. Here, James Adams shares an overview of spies and spying on both the Union and Confederate sides in the early part of the war.

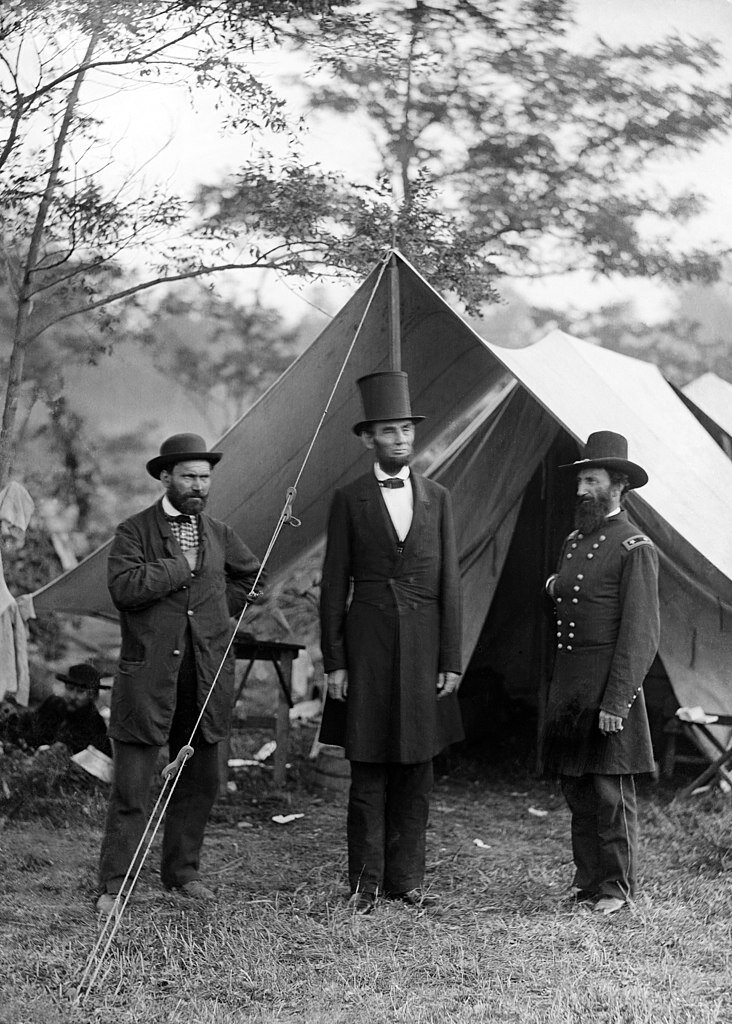

Allan Pinkerton, President Abraham Lincoln, and Major General John A. McClernand, 1862. Pinkerton was the head of the Union Intelligence Service during the early years of the war.

Although neither the Union nor the Confederation had an official military intelligence network during the US Civil War, each side obtained crucial information through espionage. From the start of the war, the Confederates set up a spy network in the federal capital of Washington, D.C., which was home to many supporters of the South.

The Confederate Signal Corps also included a secret intelligence agency known as the Secret Service Bureau, which managed espionage operations along the so-called secret line from Washington, D.C., to Richmond, Virginia.

As the Union did not have a centralized military intelligence agency, the generals took charge of collecting intelligence for their own operations. General George B. McClellan hired prominent Chicago detective Allan Pinkerton to create the Union's spy organization in mid-1861.

Confederate spies in Washington

Located 60 miles south of the Mason-Dixon line, Washington, D.C. was full of southern sympathizers when the Civil War broke out in 1861. Virginia Governor John Letcher, a former member of Congress, used his knowledge of the city to set up an emerging spy network in the capital in April 1861, after the secession of its state, but before its official entry into the Confederacy.

Thomas Jordan, a West Point graduate from Washington before the war, and Rose O'Neal Greenhow, an openly pro-South widow who was friends with a number of northern politicians, including Secretary of State William Seward and Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson, were key in this network

In July 1861 Greenhow sent coded reports across the Potomac to Jordan (now a volunteer with the Virginia militia) regarding the planned federal invasion. One of his couriers, a young woman named Bettie Duvall, dressed as a farmer to pass Union Sentries from Washington, then drove at high speed to the Fairfax Courthouse in Virginia to transmit messages to the Confederate officers stationed there.

Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard later credited information received from Greenhow in helping his rebel army achieve a surprise victory in the First Battle of Bull Run (or Manassas) on July 21, 1861.

Confederate Signal Corps and Secret Service Bureau

The Confederate Signal Corps, which operated the semaphore system used to communicate vital information between armies on the ground, also set up a secret intelligence operation known as the Secret Service Bureau.

Led by William Norris, the former Baltimore lawyer who also served as chief communications officer for the Confederation, the office managed the so-called secret line, an ever-changing mail system used to get information from Washington through the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers to Confederate officials in Richmond, Virginia. The Secret Service Bureau also managed the transmission of coded messages from Richmond to confederate agents in the North, Canada, and Europe.

A number of Confederate soldiers, particularly cavalrymen, also acted as spies or "scouts" for the rebel cause. Among the most famous were John Singleton Mosby, known as the “Gray Ghost,” who led guerrilla warfare in western Virginia during the final years of the war, and in particular J.E.B. Stuart, the famous cavalry officer whom General Robert E. Lee called "the eyes of the army".

Union Spies: Allan Pinkerton’s Secret Service

Allan Pinkerton, the founder of his own detective agency in Chicago, had gathered intelligence for Union General George B. McClellan during the early months of the civil war, while McClellan headed the Ohio department. The operation soon grew and Pinkerton soon set-up a Union spy operation in the summer of 1861, working under McClellan.

Calling himself EJ Allen, Pinkerton built a counterintelligence network in Washington and sent undercover agents to the Confederate capital of Richmond. Unfortunately, Pinkerton's intelligence reports on the ground during the 1862 peninsula campaign systematically miscalculated the Confederate numbers at two or three times their actual strength, fueling McClellan's repeated calls for reinforcements and reluctance to act.

Although he called his operation the United States Secret Service, Pinkerton actually only worked for McClellan. Union military intelligence was still decentralized at the time, as generals (and even President Lincoln) employed their own agents to seek and report information. Lafayette C. Baker, who worked for former Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott and later for War Secretary Edwin Stanton, was another important Union intelligence officer.

The courageous but ruthless Baker was known to have gathered Washingtonians suspected of having sympathies with the South; he later led the manhunt for John Wilkes Booth, the Confederate sympathizer who shot and killed Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in April 1865.

Prominent civil war spies

One of the first Confederate spies targeted by Allan Pinkerton was Rose O’Neal Greenhow. Shortly after the southern victory in the First Battle of Bull Run, Pinkerton placed Greenhow under surveillance and then arrested her. Imprisoned in Old Capitol Prison, she was released in June 1862 and sent to Richmond. Belle Boyd, another famous southern spy who became a Confederate, helped pass information to General Stonewall Jackson during his campaign in the Shenandoah Valley in 1862. Like the Confederacy, the Union also had female spies: Elizabeth Van Lew of Richmond, risked her life running a spy operation from her family's farm, while Sarah Emma Edmonds disguised herself as a black slave to enter into Confederate camps in Virginia.

Born in Britain, Timothy Webster, a former New York police officer, became an early double agent in the Civil War. Sent by Pinkerton to Richmond, Webster pretended to be a courier and managed to gain the trust of Judah P. Benjamin, the Confederate Secretary of War (later Secretary of State). Benjamin sent Webster to deliver documents to the Baltimore secessionists, which Webster quickly passed on to Pinkerton and his staff. Webster was eventually arrested, tried as a spy, and sentenced to death. Although Lincoln sent a message to President Jefferson Davis threatening to hang the Confederate spies captured if Webster was executed, the death penalty was carried out in late April 1862.

What do you think about spying in the US Civil War? Let us know below.