There has been a long and varied line of Popes throughout history. But have you heard about the Pope who drank cocaine wine? Sam Kelly explains.

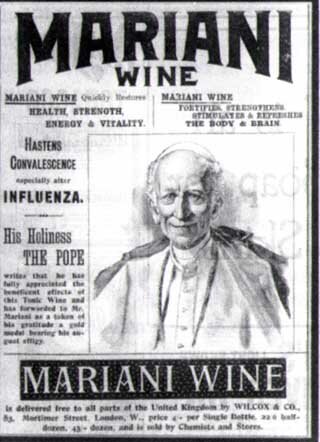

Mariani wine as drank by Pope Leo XIII.

To people who are not devout Catholics, the history of the Popes might seem dull and uninteresting. But it is filled with bizarre and fascinating characters, starting with the first pope, St. Peter, who was crucified upside down because he felt unworthy of dying in the same way as Jesus. And who can forget colorful characters like Pope Stephen VI, who dug up his predecessor’s corpse, put it on trial, found it guilty, hacked off its fingers, and threw it in the Tiber River? Or Pope John XII, who murdered several people in cold blood, gambled with church offerings, and was killed by a man who found him in bed with his wife? Or Pope Urban VI, who complained he didn’t hear enough screaming when the cardinals who conspired against him were being tortured? Or Pope Alexander VI of the notorious Borgia crime family, who bribed his way into the job, engaged in a litany of corruption including nepotism, murder and orgies, went on to father nine illegitimate children, and whose corpse was left unattended for so long that it became so bloated and swollen it couldn’t fit into its coffin?

There have been plenty of good Popes, too, and one of these was Pope Leo XIII. One of the longest-serving Popes, he remained the head of the Catholic Church until he died at age 93. He was a forward-thinking intellectual whose goal was to reinvigorate the Church, at a time when many Europeans felt it had become irrelevant to their lives because it was stuck in the past. Leo sought to emphasize that religion was compatible with modern life. He spoke passionately about workers having a right to fair wages, safe working conditions, and the importance of labor unions. He was a skilled international diplomat who succeeded in improving relations with a host of countries including Russia, Germany, France and the United States, and he wholeheartedly embraced science and technology. He was the first Pope whose voice was recorded on audio, and the first to be filmed by a prototype movie camera (which he blessed while it was filming him).

The Most Productive Pope of All Time

But what he is best known for is how insanely productive he was. He wrote more encyclicals than any other Pope in history. An encyclical is a letter from the Pope to all of the bishops in the Roman Catholic Church, but more importantly, it is the way the Pope announces his official view on important topics. Encyclicals are deep, thoughtful and expansive, which means they tend to be lengthy. Since the beginning of time, there have been 300 papal encyclicals, and Leo XIII wrote 88 of them. That’s right, this one man wrote 30% of all encyclicals. He wrote on topics big and small – huge concepts such as liberty, marriage and immigration, but he also wrote 11 encyclicals focused wholly on the subject of rosaries. Scholars have always been amazed by his prodigious output, and bear in mind he was an extremely old man, serving as Pope well into his 80s and 90s. Yet he remained a tireless workhorse. Where did he find the energy?

It was probably the cocaine.

Popes have always loved wine. Forward-thinker that he was, Leo XIII brought something new to the mix. He drank wine laced with cocaine. This was not some home-brewed mix he created himself; it was an actual product you could buy in stores – a magical elixir known as Vin Mariani. For Leo, its primary appeal was the energy it gave him. It had a powerful kick that kept the Pope perpetually in the mood to philosophize and pontificate, which is probably what allowed him to write those 88 encyclicals in 25 years.

Leo absolutely loved the stuff and wasn’t shy about saying so. He proclaimed to everyone that he carried the salubrious libation with him at all times in a personal hip flask – “to fortify himself when prayer was insufficient.” Yes, he actually said those words. This being the 19th century, cocaine was neither illegal nor stigmatized. It was viewed with wonder and awe by the European medical establishment. Vin Mariani was seen not only as a health tonic, but as a prestigious and sophisticated beverage on par with a fine vintage wine.

Many Famous Drinkers of Cocaine Wine

Many famous people were Vin Mariani drinkers. Thomas Edison said it helped him stay awake longer. Ulysses S. Grant drank it while writing his memoirs. Emile Zola wrote testimonials that were reprinted in Vin Mariani advertisements. Even Queen Victoria was a big fan.

Pope Leo loved Mariani-brand cocaine wine so much that he decided he must meet and properly honor the man who invented it. He summoned Angelo Mariani to Rome and presented him with an official Vatican gold medal to congratulate him for his remarkable achievement in the field of cocaine vintnery.

At this point, you are probably thinking I have gone too far. A pope who loved cocaine is a funny idea, and maybe there are some dubious rumors scattered around the Internet that Pope Leo enjoyed the taste of cocaine wine, but there’s no actual proof he did so, right? And he certainly didn’t hand out a gold medal to his drug dealer, did he? After all, it’s not like he appeared in a full-page advertisement touting the benefits of cocaine wine…

No, I’m lying, he totally did.

Angelo Mariani printed up posters advertising the gold medal he received from the Pope. The poster features a huge smiling image of Pope Leo, and next to his picture there is text which reads: “His Holiness the Pope writes that he has fully appreciated the beneficial effects of this Tonic Wine, and has forwarded to Mr. Mariani as a token of his gratitude a gold medal bearing his august effigy.” That’s right, the Pope himself knowingly appeared in a full-page advertisement for cocaine wine.

Things were simpler back then.

Now read Sam’s article on Queen Victoria and the First Opium War here.

References

Drew Kann, “Eight of the Worst Popes in Church History,” CNN.com, April 15, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/10/europe/catholic-church-most-controversial-popes/index.html

Ishaan Tharoor, “7 Wicked Popes, and the Terrible Things They Did,” The Washington Post, September 24, 2015,https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/09/24/7-wicked-popes-and-the-terrible-things-they-did/

“Leo XIII,” Britannica, updated February 26, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leo-XIII

James Hamblin, “Why We Took Cocaine Out of Soda,” The Atlantic, January 31, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/01/why-we-took-cocaine-out-of-soda/272694/

Wyatt Redd, “Vin Mariani – The Cocaine-Laced Wine Loved by Popes, Thomas Edison, and Ulysses S. Grant,”Allthatsinteresting.com, January 31, 2018, https://allthatsinteresting.com/vin-mariani