The Roman Republic lasted from 509 BC to 27 BC. It started after the period of the Roman Kings and ended with the start of the Roman Empire. Here, Cameron Sweeney explains how government operated in the Roman Republic. It considers the Senate, the Assembly, the Quaestors, Aediles, and Praetors, the Consuls, and the Censors.

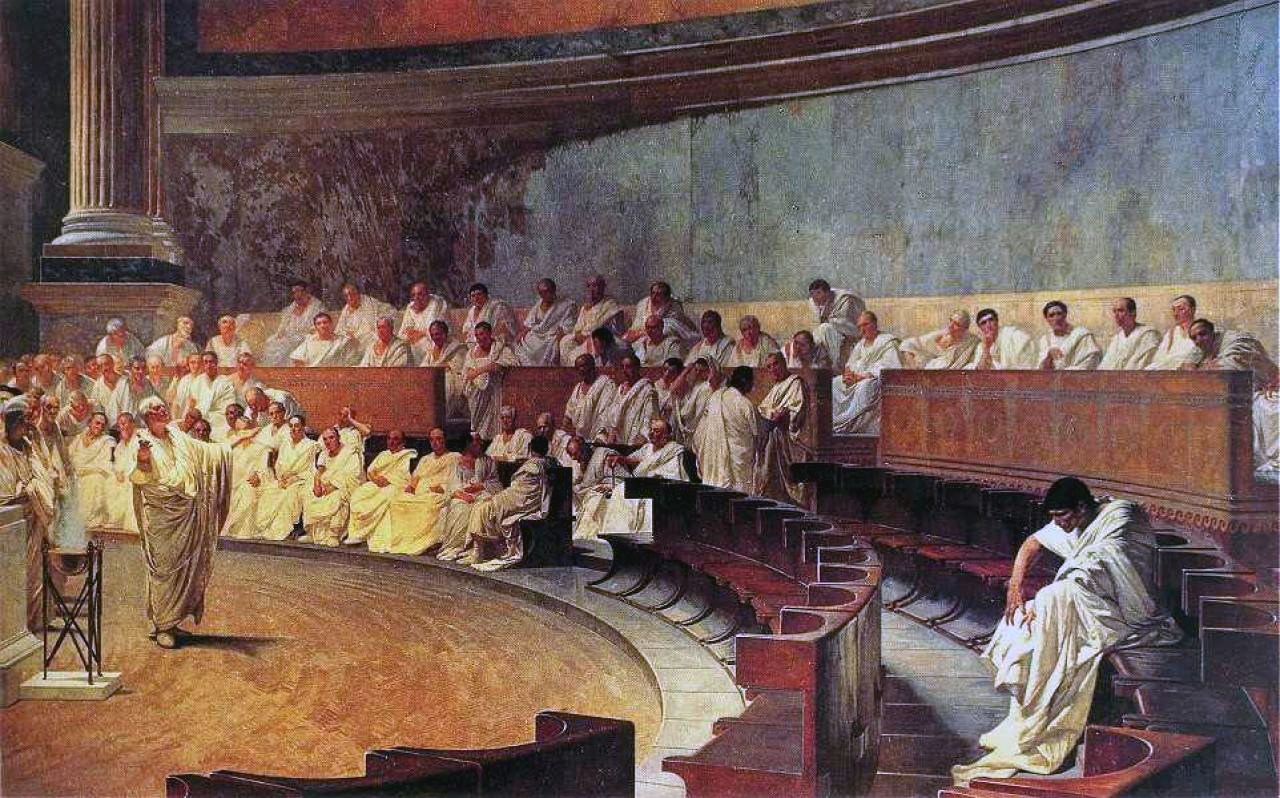

a 19th-century depiction of the Roman Senate by Cesare Maccari. The painting is called Cicero attacks Catiline.

Rome. Surely the best-known empire in the history of mankind. Rome has left behind it a legacy of art, philosophy, literature, and architecture (and a horse Consul, but we will ignore that). People know of the writings of Seneca, or of the story of Aeneid, or even about the aqueducts and Coliseum. Whether it be when Caligula declared war on Neptune or the stories of Julius Caesar, people typically know quite a bit about Rome. But what many people don't know about is their government. The Romans have left a mold in which western civilizations have used in the formation of their government.

Social Divisions During the Republic

Up until Julius Caesar took hold of Rome in 49 BC, Rome was not ruled by an all-powerful individual, but by two elected Consuls. At that time, Rome was considered a Republic, and Rome was the closest it would ever be to a democracy.

The citizens of the Republic were broken up into three main social classes; the Patricians, Plebeians, and Slaves.

The patricians were usually the wealthiest and elite families of Rome. I emphasize families because Rome was a society where even the wealthiest plebeians weren't considered patricians, due to their “gens” or name. Patricians lived in grand villas and had slaves do their work for them. Due to their elite social class, they were allowed to vote and participate in government.

The plebeians were the lower class of Rome. Typically without wealth or slaves, the plebeian class usually had to work for a living (an utterly repulsiveidea, I know). It was not uncommon, however, for a wealthy plebeian to buy their way into the patrician class, if a certain patrician family was in dire need of funds. Regardless of this, Plebeians were still citizens of Rome and thus were also allowed to vote and participate in government.

The slave class of Rome, on the other hand, had no money, no land, and no freedoms. Although slaves, they had some rights and often would occupy important positions such as accountants or physicians. Nonetheless, they were not considered citizens of Rome and were not allowed the right to vote or participate in government.

The Senate

Throughout the history of Rome, the Senate played an important part in Roman politics and government. The Senate consisted of men aged 30 or older, and senators held their office for their entire life! Senators would advise the Consuls, and even the Emperor later in Roman history, and would often discuss and vote on legislation.

What makes the Senate interesting is that it had no legislative power. That's right, the Senate had no power to create or destroy laws. This didn't make it powerless, as the Senate still held a significant influence over government and acted as a prime advisory body to the Consuls in the time of the Republic.

During the time of the Emperor the Senate naturally lost significant power. Even so, the Senate discussed domestic and foreign policy and supervised relations with foreign powers and governments. The Senate would direct the religious life of Rome and, most importantly, controlled state finances. The ability to control finance was an incredible tool for the Senate's disposal, as that gave them leverage when the Germanic tribes decided they wanted to give taking over Rome just one more try, and the Emperor needed additional funds to wage war.

The Assembly

Throughout Rome, there were several different assemblies that held legislative power. The Senate may have held influence over legislation and policy, but the assemblies had legislative power. The most prominent assembly was the “Concilium Plebis,” or the Council of the Plebeians. This assembly allowed Plebeians to gain a say in Roman law. These assemblies acted as the voice of Rome and portrayed the needs and desires of the general public.

Even more so than the elite Senate, these assemblies represented the voice of the plebeians, and even more, the voice of the ordinary citizens of Rome. By no means was this system fully democratic, but the establishment of these assemblies was one of the first steps to modern democracy, that is used in many nations today. The assemblies’ critical role in Roman government is what gave it a name in their military standard, SPQR - "Senatus Populusque Romanus."

The Quaestors, Aediles, and Praetors

At the very beginning of the Roman Republic, people quickly realized that they would need magistrates to oversee various administrative tasks and positions. Over time, these positions became known to be sort of a “path to consulship.” Each position had a different task and purpose to fulfil.

The first step of the “path to consulship” was the Quaestor. Men 30 years (28 if you were a patrician) or older were eligible to run. Quaestors served in various financial positions throughout the Empire. Quaestors did not possess the power of imperium and were not guarded by Lictors Guild.

The next step was the Aediles. At 36 years old, former Quaestors were allowed to run for Aedile. At any time there were four Aediles, two patricians and two plebeians, each of which were elected by the Council of the Plebeians. They were entrusted with administrative positions, such as caring for public buildings and temples or organizing games. This ability to organize games was critical to boosting any aspiring politicians popularity with the people, and was certainly utilized to its fullest.

The final step to Consulship was the Praetor. After occupying the office of the Aediles or Quaestor, a man of 39 years could run for office. In the absence of either Consul, a Praetor would hold command over the garrison. The main purpose of the Praetor, however, was to act as a judge.

The Consuls

The two consuls of the Roman Republic really represented two main things; an executive branch, and checks and balances. With the establishment of Consulship after the fall of the Roman Kings, this showed the beginning of an executive branch, in the sense that there is one, or two in the case of the Romans, powerful head(s) of a government. What made this system interesting is that there were two Consuls at any given time, and bothcould veto each other.

Giving this executive, the Consul, the power of veto is another addition into Roman checks and balances put in place to keep one man from ruling all of Rome, which is why there was never a Roman Emperor… Oh, wait a second… Anyway… Up until Caesar, Romans kept the Consuls in check through their own system of checks and balances. Since both Consuls could veto each other, and there was an assembly to vote and discuss laws, the Consul was kept from overpowering Roman government.

The Consul had the power of Imperium,or basically the power to lead the army, presided over the Senate, and represented the state in foreign affairs. That being said, even with checks and balances, each Consul wielded significant power. Once Rome was ruled by Emperors, the office of the Consul dramatically lost its powers to the Emperor, but was still maintained as a sort of symbolic reminder of Rome’s Republican past and where they came from.

The Censors & Magister Populi

Becoming a Censor in Rome was considered the pinnacleof public office for several reasons. During the time of the Republic, the Censor held an 18 month term, as opposed to the usual 12 month terms. This position was elected every five years and although without the power of imperium, it was still considered a great honor.

Censors not only counted the population, or census, in Rome but had the ability to add and remove Senators from office, as well as construct public buildings. An example of this being Appius Claudius, who sanctioned the first aqueduct.

The last “public office,” that needs to be brought up is that of the dictator, or Magister Populi.In times of immense danger or crisis, the people would elect one of the sitting Consuls to adopt the title of Magister Populi, or Master of the People. This position served for six months and essentially ruled as an Emperor, with total power. This position continued until Julius Caesar was named dictator for life by the Senate, and the position would never be used again thereafter. Unfortunately in 44 BC, Caesar was stabbed in the back… literally… 23 times… His death ultimately ended the Republic, and began the reign of the Emperors.

Conclusion

The Roman Republic, and SPQR in general had been a civilization that stood the test of time, and ultimately existed for roughly 1800 years.The way they wrote, sculpted, and governed shaped, and continues to shape, the world we live in today. Their ability to govern, reform, and adapt to their growing environment is what ultimately allowed them to exist for almost two millennia, and prove themselves such a successful civilization.

What do you think about Roman Government? Let us know below.

References

“The Romans - Roman Government.” History, 11 May 2017, www.historyonthenet.com/the-romans-roman-government/.

“The Roman Republic.” Ushistory.org, Independence Hall Association,www.ushistory.org/civ/6a.asp.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Roman Republic.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 3 Apr. 2018, www.britannica.com/place/Roman-Republic.