The US Supreme Court becomes a very important political issue whenever a vacancy arises. Here, Jonathan Hennika looks at the history of the US Supreme Court and the importance of Marbury v Madison, the ruling that established judicial review and that allows courts to strike down unconstitutional government actions.

William Marbury. Painting by Rembrandt Peale.

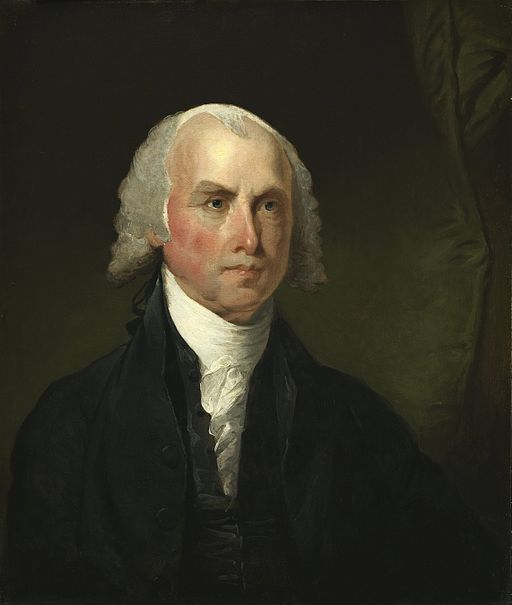

James Maddison. Painting by Gilbert Stuart.

The recent confirmation battle over President Trump’s choice to replace Justice Anthony Kennedy was a critical moment for the Judiciary. During the news coverage, some analysts commented on the framer’s intentions for the Supreme Court to be apolitical. Richard Wolffe, a columnist for The Guardian, quoted Nebraska Senator Deb Fisher in a recent piece on the confirmation battle: “Judges make decisions based on law, not on policy, not based on political pressure, not based on the identity of the parties.”[i] An examination of Supreme Court presidence indicates that Judges do make decisions based on political pressure, policy, and/or party/regional identification. In fact, it was the fear of political pressure that guided Chief Justice John Marshall in writing his majority opinion in the case of Marbury v Madison.

Marbury v Madison: The Question of Judicial Review

Writing in 1912, Constitutional historian Andrew C. McLaughlin defined the theory of judicial review as the right of “any court [to] exercise the power of holding acts invalid, in doing so, it assumes no special and peculiar role; for the duty of the court is to declare what the law is, and, on the other hand, not to recognize and apply what the law is not…. This authority then in part arose…from the conviction that the courts were not under the control of a coordinate branch of the government but entirely able to interpret the constitution themselves when acting in their ownfield.”[ii] To reach this definition, Professor McLaughlin utilized the majority opinion issued in the case of Marbury v Madison, 5 US 137, (1803). Commonly taught in high school civics classes,Marbury v Madison established the right of the Judiciary branch to rule on the Constitutionality of laws enacted by either the Legislative branch or orders issued by the Executive branch. This concept, cleverly called a “balance of power” has weaved its way through the American narrative since the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1879.

What then was the case of Marbury v Madison? While serving as Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of State, founding father and future President, James Madison refused the commission of William Marbury to a federal judge post. The decision to hold up Marbury’s commission was a political one on the part of Jefferson and Madison. Marbury was one of sixty last-minute appointments that Federalist John Adams made to the judicial branch in his final forty-eight hoursin the office. The incoming Jefferson was an ardent Democratic-Republican and opposed the selectionof the “Midnight Judges,” the derisive name given by anti-federalist proponents.[iii]

Marbury filed for a Writ of Mandamus (an order enforcing the issuance of his Commission) with the Supreme Court. The Court issued its ruling on February 24, 1803. In writing the majority opinion[iv], Chief Justice John Marshall broke the case down to three questions: (i) Did Marbury have a right to his commission; (ii) If Marbury had a right to his commission, is there a legal remedy available for him to have it; and (iii)If there was a remedy, what was it, and was the Supreme Court the proper jurisdiction?[v]

The Determination of the Court

The Court ruled yes to the first two questions. It is the answer to the third question that we begin a discussion of judicial review and the Supreme Court’s place in the ConstitutionalRepublic. Madison’s argument was the Commissions arrived athis office late, i.e.,after Jefferson’s inauguration, and as such, the commissions were invalid. The Court rejected this argument, writing: “The [President's] signature is a warrant for affixing the great seal to the commission, and the great seal is only to be affixedto an instrument which is complete. [...] The transmission of the commission is a practice directed by convenience, but not by law. It cannot, therefore, be necessary to constitute the appointment, which must precede it and which is the mere act of the President.” As to the second question, the Marshall Court concluded: “The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws whenever he receives an injury. One of the first duties of government is to afford that protection. The Government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right.”[vi]

The third questionbecame pivotal. Marshall knew that the Court was in a precarious political position. If the Court ruled in favor of Marbury,the implication was the judiciary favored the Federalist cause. Marshall also believed that Jefferson and Madison potentially might ignore any order to issue the commission, thus showing the inherent weakness of the Judicial Branch. This weakness, the inability to enforce its rulings, will appear again in the fallout of the Brown v Board of Educationdecision in the 1950s. However, Marshall was not comfortable with a rulingagainst Mr. Marbury, handing Jefferson a political victory.

The decision then became that the Supreme Court did not have jurisdiction to make a ruling for or against Marbury. To avoid the appearance of a political victory for Jefferson, the Marshall Court tempered the decision by enacting judicial review. Procedurally, the Supreme Court heard the case under the Judiciary Act of 1789. The relevant part of the law read “The Supreme Court shall have powerto issue writs of prohibition to the district courts, when proceeding as courts of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction, and writs of mandamus, in cases warranted by the principles and usages of law, to any courts appointed, or persons holding office, under the authority of the United States.”[vii]Marshall ruled that this portion of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional. In the ruling, Marshall cited Article Three of the Constitution which laid out the duties and the responsibilities of the Supreme Court. Under the concept of judicial review, Marshall determined that Congress had violated the Constitution when it laid out functions regarding the dutiesand obligations of the Supreme Court. Thus, while the Supreme Court was constitutionally boundto hear the case of Marbury v Madison; it was not constitutionally bound to issue a ruling.

The Specter of Political Influence

To make the Court apolitical, Marshall had to become political. He allowed the appearance of political influence on the judiciary to influence the judiciary’s decision in Marbury. Strengthening the Marburydecision was theCourt’s ruling in McCulloch v Maryland17 US 316 (1819). In a case brought surrounding the constitutionality of the Second Bank of the United States, the Court ruled that the Constitution granted Congress implied powers to implement the powersexpressed in the Constitution for there to be a functional national government. In other words, if McCullochcamefirst, then a decision needed to be rendered in Marbury v Madison because the Judiciary Act of 1789 was an example of a Congressional implied power used to aid an expressed power of the Constitution. The precedents of Marbury and McCullochcemented the definition of the judiciary as the ultimatearbiter on all questions Constitutional. They helped define the role of the legislative branch. These cases are pointed to as the cornerstones of American Jurisprudence and holds the Supreme Court above the political fray. The decisions that defined the roles of the Judicial and Legislative branches were based, in part, on political pressure and the identity of the nascent parties.

The paradox of an apolitical Supreme Court shows itself throughoutitscareer. The laws at the heart of their decisions are born from politics, so how can the Supreme Court maintain an apolitical position? Unfortunately, the Court cannot negate the intertwining of its rulings and the Court of Public Opinion, a.k.a. Politics.

What do you think of the Marbury v Madison ruling? Let us know below.

[i]Richard Wolff. “Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation isn’t democracy. It’s a judicial coup,” The Guardian, October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/oct/06/brett-kavanaugh-confirmation-supreme-court-republicans

[ii]Andrew McLauchlin as quoted in Edward S. Corwin, “Marbury v Madison and the Doctrine of Judicial Review,” Michigan Law Review, 12 (May, 1914), 548.

[iii]Paul Brest, Sandord Levinson, et al Process of Constitutional Decision-making: Cases and Materials (New York: Wolters Kluwer, 2018), 115

[iv]However, there was no minority opinion as the decision of the Marshall Court was a unanimous vote of 4-0.

[v]Erin ChemerinskyConstitutional Law: Principles and Policies.(New York: Wolters Kluwer, 2015). 39.

[vi]Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 at 158, 160, 163

[vii]Judiciary Act, 1stCongress, Sess. I. Ch 20 1789, 80-81