The Salem witch trials are one of the most infamous events of 17th century America, ultimately leading to the death of many women in Salem. But what were the events that caused the trials? Here Kaitlyn Beck explores the history of Salem, and how the quest for power, medicine, and religion all had their influences on the witch-hunt.

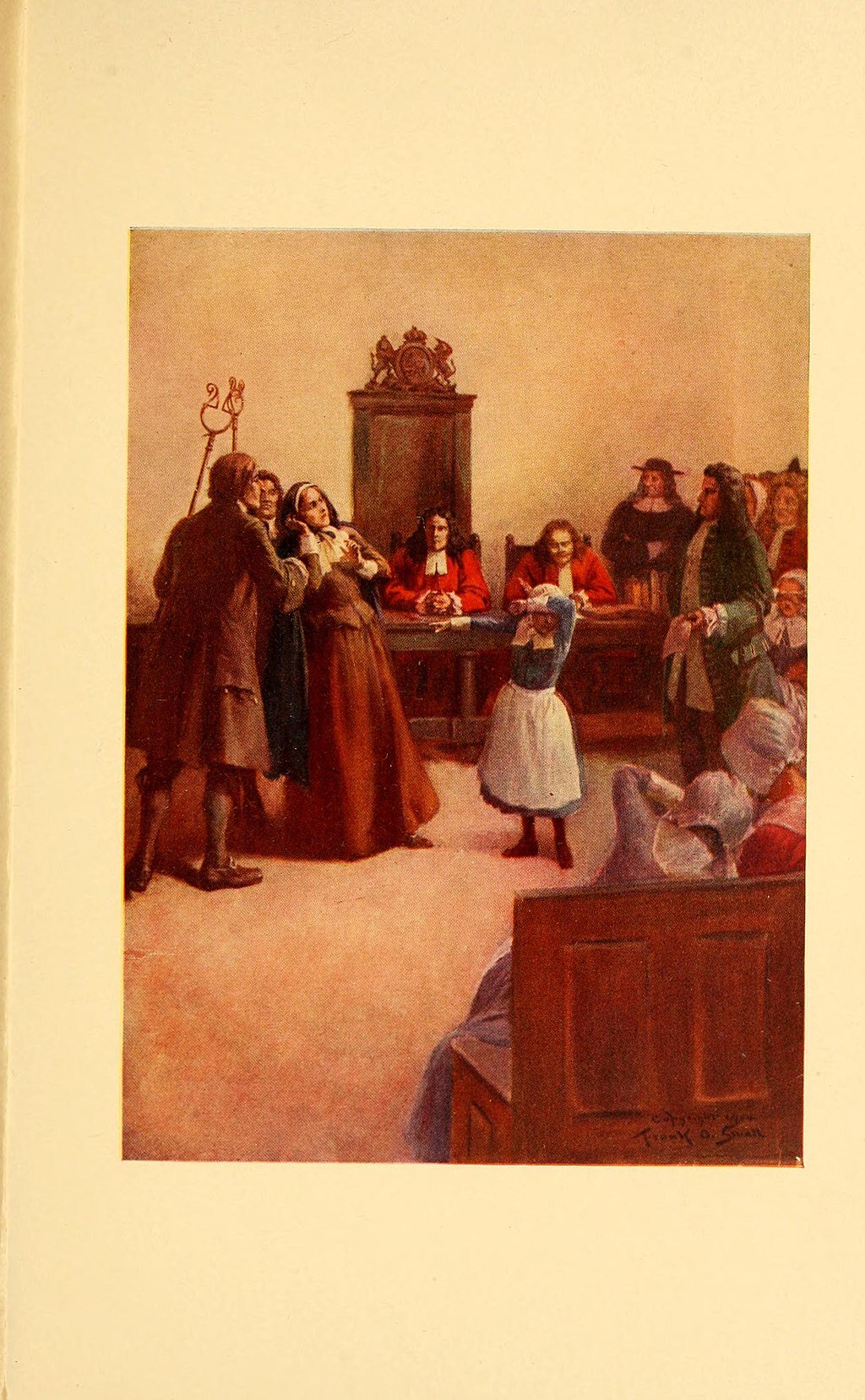

An image of the Salem witch trials by Frank O. Small.

In January of 1692, nine-year-old Betty Parris began to exhibit unusual behavior including loud cries and convulsions. By mid-February, her cousin Abigail began to exhibit the same symptoms and Pastor Parris decided to consult with the Dr. William Griggs, the town physician. After weeks of observation, Griggs concluded that “the evil hand is upon them”, known by the people as a diagnosis of witchcraft (Dashiell). This was the beginning of the Salem Witch Trials.

In the midst of political and cultural unrest, Dr. William Griggs’ medical diagnosis of witchcraft became the catalyst that started the Salem Witchcraft trials of 1692. Before the start of these infamous witch trials, Salem was veering away from its ‘City on a Hill’ ideals. With divided loyalties and slow retraction from the Puritan faith that the town was founded upon, prominent members of its society were concerned of what would become of their town. When young girls began to show signs of unnatural behavior that none could explain, the town was distraught. Such circumstances created a powder keg, needing only an official word to create the explosion that was the Salem Witch trials.

The 1680s in Salem

During the 1680s, Salem was going through a period of political unrest. Two families were battling for control: the Putnams and the Porters. The Putnams arrived in the early 1640s and were successful in acquiring large amounts of land. However by the late 1680s, their wealth and political influence were on the decline. In contrast, the Porters were, according to the 1680s census, wealthier and more affluent. The two families vied for control and had different plans for Salem’s future. The Putnams wanted to separate the village from the rest of Salem while the Porters wished to keep it unified. Each family had certain factions of control. For the Putnams, they had allies amongst the oldest families who knew them in their more affluent years. The Porters controlled the council and made friends with those who wished for a change in Salem’s priorities. As a result of rising tensions, many (but not all) members of Salem began to align themselves with one of these families. This was certainly the case with Dr. Griggs, who was connected to the Putnams by marriage(Hoffer 39-45). During the trials, Dr. Griggs fervently supported the “afflicted” girls, who included Ann Putnam and his own great-niece Elizabeth Hubbard (Dashiell). Another supporter of the Putnams was Pastor Samuel Parris who was at odds with the town committee, which was controlled by the Porters (Hoffer 53). With such powerful friends vying for control of both town and church, Dr. Griggs certainly felt pressure to make a diagnosis that would be beneficial to the Putnams which, by extension, would benefit him as well.

The diagnosis of witchcraft would not have been as powerful if not for the influence of medicine in colonial America. When illness arose, women were commonly in charge of caring for the sick except when the illness was long lasting or too intense for basic herbal remedies. The study of formal medical practice had its roots in Europe, in particular the University of Edinburgh (Twiss). Far from Europe and its schools, many colonial doctors were not formally trained (Mann). At best, they worked as apprentices under formally trained doctors from England (Twiss 541). In addition, colonial doctors also battled lack of sanitation laws, shortage of drugs, and outdated medical knowledge (Twiss 541). Of Dr. Griggs, not much is known about his training as a physician. He originally came from Boston and was the first doctor to practice in Salem (Robinson 117). Most likely, he had little to no training in formal medicine (Dashiell). In fact, some historians believe that Dr. Griggs combined his limited medical knowledge with folk magic. In fact, ‘folk’ magic was had its origins in England and was used in the colonies on many occasions. Shortly after Griggs made his diagnosis but before any formal accusations, a form of folk magic, termed ‘white magic’ was attempted to discover the one responsible for the girls’ illness. Titubia and her husband John Indian baked a ‘witch cake’; this was fed to the dog of a suspected witch (a witch’s familiar). If successful, this mixture of ordinary meal and victim’s urine would reveal and hurt the witch (Konig 169). When Dr. Griggs’ diagnosis was known throughout Salem, such practices went under fire as being pure witchcraft. As a result, people looked even more towards medicine and the Puritan faith to guide them.

Religion and Medicine

Colonial Medicine was not only based on pure science; in fact, medicine often intertwined with religion, especially in a town founded on strict Puritanism. As a result, Reverend Parris and Dr. Griggs were two of the most powerful men in Salem (Robinson 136). When Betty first began to exhibit her unusual behavior, Parris and other ministers tried to invoke the power of prayer to heal her. When this failed to work, Parris called in the next highest power, a male physician, to make Betty better (Hoffer 62-63). When Dr. Griggs could find no physical explanations for the girls’ ailments, he put the blame on witchcraft. This was a serious accusation for at the time, English law (as of 1641) stated witchcraft was a capital offense (Krystek). Though serious, witchcraft was a common diagnosis for unexplainable illnesses; it was sometimes believed to be punishment from an angry God (Dashiell). Dr. Griggs’ initial diagnosis would not be the last; in fact records show Dr. Griggs repeating this diagnosis; in May of 1692, he accounted witchcraft as the cause of illness for Daniel Wilkin, Elizabeth Hubbard, Anne Putnam Jr., and Mary Walcott (Robinson 184&190). Though the people of Salem knew of witchcraft, it took an official diagnosis from a doctor for others to take action.

Change in Salem

Life in Salem had always been difficult. The winters were very cold, the land was rocky and hard to farm, and the threat of disease and illness was constant (Krystek). King Phillip’s War was still fresh in the memories of the town people. They knew about the hundreds of men, women, and children killed in Native American raids. The town was kept in a constant state of fear, frightened by their close proximity to Native American settlements and at the possibilities of renewed attacks (Hoffer 55-56). As the external forces grew more threatening, the internal structure began to crumble. Salem was built on the ideas of harmony and the importance of a cooperative community. Puritanism was the glue that held this community together. The Bible was taken as a guide to life, down to the smallest details. To them, the Word of God was clarity, making a clear division of right and wrong, all in black and white terms (Erikson 47). But in the late 1600s, townspeople were drifting from the original principles of this community. The younger generations were less keen on spiritual matters, resulting in decreased church attendance and membership (Hoffer 53). Others turned their focus from a church centered life to one of worldly pursuits, delving into practices such as mercantilism and fulfilling individualistic needs and wants over those of the group (Hoffer 40). This drive towards mercantilism was propelled by one of the most prominent families in Salem: the Porters. They desired to unify the town not by a common belief but by a common market (Hoffer 45). For the other prominent, male members of the town (especially the Putnams and their supporters, including Dr. Griggs), there was a need for extreme reformation.

Witchcraft to bring Salem together?

The many who were unsatisfied with their way of life, particularly the women, were seen as a threat to their male driven society. This would become a prevalent fact when accusations began; women who did not follow the traditional role were often the first to be accused (Erikson 143). The clearest example was the first three women brought to court (accused of bewitching Betty and Abigail Paris), an action immediately influenced by Dr. Griggs’ diagnosis. Each woman exemplified qualities the leaders of Salem wished to eradicate. Tituba was a woman of color who dabbled in voodoo and was considered an unsavory influence on the younger girls. Sarah Good was an older woman with a sour disposition, creating discord with her neighbors. Sarah Osbourne did not attend church and was the center of a social scandal where it was rumored that she moved in with a man before marriage (Erikson 143). Getting rid of such independent and un-conforming women was made easier by the traditions known of witchcraft, the main one being that, more often than not, witchcraft was practiced primarily by women (Karlsen 39). Once the diagnosis was made public and the young girls began naming witches, women such as these, who did not follow the traditional roles that had been abided by for decades, would be cleansed from Salem.

The diagnosis of witchcraft was the perfect opportunity to bring Salem together. The word of witchcraft quickly spread amongst the small village and people began to come together in order to accuse/bear witness to the ‘witches’ plaguing their town. The hysteria created by these trials did not create total disorder. In fact, witchcraft became so imbedded in their society during this time that it highlighted the significance of the community. For many years prior, people had lost sight of the relevance of Puritanism in an increasingly economic driven world. So when a ‘professional’ medical verdict was announced, citizens responded to the validity but looked back to their Puritan roots. It reminded the Puritans of their participation in the cosmic struggle between good and evil (Demos 309-310). Finally, restoring the community under faith brought the control and conformity back to the church and the men who controlled it.

Conclusion

By the time the witch trials were ended in May of 1693, 141 people had been accused, 19 had been hung as witches, and 4 had died in jail (Krystek). The backdrop for these trials was made years before the first accusations. Struggles for power in the government were reaching their peak and the people were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with their life. Worse, people were drifting away from the faith that had kept them together since its founding. Dr. Griggs’ diagnosis of witchcraft was powerful enough to start such a radical movement because of the influence of medicine that was closely intertwined with religion and, in his case, powerful friends. His diagnosis was the real push that Salem needed to begin a Witch Hunt that would shake the town at its core and leave repercussions for years to come.

What do you think caused the Salem witch trials? Let us know below.

References

Dashiell, Beckie. Dr. William Griggs. Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. University of Virginia, 2006. Web. 10 February 2014.

Demos, John Putnam. Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. Print.

Erikson, Kai T. Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1966. Print.

Hoffer, Peter Charles. The Devil’s Disciples: Makers of the Salem Witchcraft Trials. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996. Print.

Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987. Print.

Konig, David Thomas. Law and Society in Puritan Massachusetts: Essex County 1629-1692. University of North Carolina Press, 1979. Print.

Krystek, Lee. The Witches of Salem: The Events of 1692. The Museum of Unnatural History, 2006. Web. 11 February 2014.

Mann, Laurie. Changing Medical Practices in Early America. Changing of Mapscape of West Boylston, 2013. Web. 15 March 2014.

Robinson, Enders A. The Devil Discovered: Salem Witchcraft of 1692. Prospect Heights: Wavelands Press, 1991. Print.

Twiss, J.R. “Medical Practice in Colonial America”. New York Academy of Medicine(1960) 533-551. Web. 16 March 2014.