Much of the modern Irish identity is drawn from the belief that it is “Celtic.” This is evident in the many Irish art styles, music, symbols and sports clubs that take the name “Celtic.” But what is “Celtic”? And does it have anything to do with Ireland? Jackie Mead explains.

You can read Jackie’s previous article on Lewis Temple and the 19th century whaling industry here.

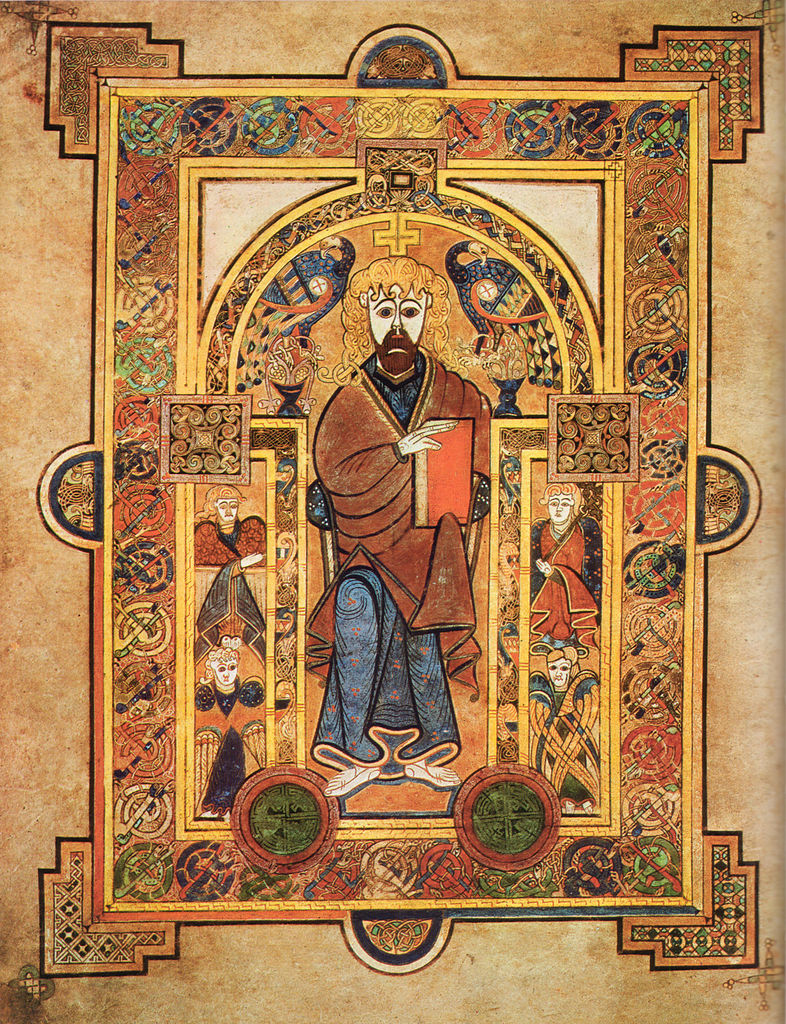

Jesus Christ as shown in the 9th century Book of Kells.

Who Were the Celts?

The word “Celt” comes from the Greek word “Keltoi,” used to refer to barbarians on the border of their empire. It is unlikely that these groups used the name to refer to themselves. For many years, academics believed that this group, loosely affiliated through culture, linguistics, and art style, was able to conquer much of mainland Europe and Ireland in the Late Bronze Age. This meant the new culture became the foundation of modern Irish culture, since the Irish natives of the time would not have been as strong as that of these continental invaders. However, those same academics were unsure as to when this group arrived, where they originated, and what technologies they brought.[1]

Social Darwinism and Archeology

The Celtic invasion theory was able to take hold so effectively because invasion was already believed to be a common theme in Irish history. Early medieval pseudo-history stated that the modern Irish were the descendants of Mil, a biblical figure who traveled to the Iberian Peninsula and started the race that would eventually rule Ireland.[2]Continuing on this vein of thinking, nineteenth century archeologists believed that a new material culture in the archeological record indicated the arrival of a new, invading group (because, of course, it was simply not possible that one group could have twoart styles).

There were contemporary political motivations for this. At the time, Ireland was in a colonial relationship with England, and English scientists were attempting to rationalize Britain’s colonial empire through Social Darwinism. While the English were asserting that they were of a superior Germanic race, they were searching for an inferior origin for the Irish.[3]This led to a frantic search to find evidence that the Irish were descended from a barbaric continental tribe.[4]

Debunking the Myth

Archeology is a major player in the academic debate surrounding the Celts. Armies drop a lot of stuff, so some of that stuff would have ended up in the ground. But archeologists found a significant continuity throughout Irish prehistory. There is no sudden change in technology in the Late Bronze Age. The first iron objects were made to resemble traditional bronze objects, suggesting that they were made by the same people. Living conditions were similar as well; many Iron Age sites rest on reused Bronze Age hill forts.[5]Religious practices such as ritual deposition (purposefully dropping valuable objects into bogs and lakes) were also continued in the Iron Age, along with the burial traditions of cremation and single-grave tradition.[6]With all of these continuities, it seems highly unlikely that an invasion on a large scale could have taken place.

One of the most commonly turned to pieces of evidence for a Celtic invasion is the spread of the La Tène art style. This highly stylized curvilinear art style was very popular in the late Bronze Age, spreading from the Austrian-Switzerland region to Hungary, France, Germany, and Ireland. The English academics believed the Celtics invented La Tène and dropped it like a business card wherever they conquered a new territory. Antiquities expert John Collis calls this kind of association “dubious in the extreme.”[7]The theory completely ignores the fact that art can spread because people like it, not because it was brought by an invading army. Secondly, it fails to account for the fact that La Tène was almost exclusively a commodity for a very small group of wealthy people. An empire built on this art style would have been a very lonely one, and devoid of lower classes.[8]

It is far more likely that La Tène was brought to Ireland through contacts in Britain and on the Continent. Several pieces of the art have been found to be imported from these places, although the majority of it is Irish made.[9]Based on this evidence, La Tène is no longer considered to be the basis for the Celtic empire.

Pollen Evidence

Some of the most convincing evidence against the existence of a Celtic invasion comes from pollen. Pollen diagrams show that there was a resurgence of tree growth during the period, which indicates that there was a significant decrease in farming. It also shows that areas of Ireland were experiencing bog growth, which is unfit for human habitation.[10]Archeologists also had difficulty finding Iron Age sites to study, which means that there were less people during the period. The diminished population could not maintain the booming economy of the Late Bronze Age. An invading army, especially one that supposedly possessed great advancements in weaponry and art, would have boosted the economy and increased the population.[11]

Why Do the Irish Embrace Being Celtic?

If the ideas behind Ireland’s Celtic identity are not only wrong, but also racist, why have the Irish embraced it so much? Because, oddly enough, the English attempts to separate themselves from the Irish backfired spectacularly. Ireland had spent much of its history politically divided, and the new nationalist movement required a shared history. The idea of the Celt, a race that was separate from the British and had no right to be colonized by the descendants of Saxons, was created.[12]Douglas Hyde, the first President of Ireland, once wrote: “The sense of nationhood among the Irish stems from the half unconscious feeling that the Celtic race, which at one time held possession of more than half of Europe, is now making its last stand for independence on this island of Ireland.”[13]

The Celts of Today

Shared history is a powerful ingredient to nationalism, and the Celts became that for the Irish.[14]They fully embraced the biased literature of the period, embracing the so-called Celtic art style, music style, and spirituality. Today, the idea of the Irish Celt has been debunked in academia, but lives in on popular Irish culture.

As it became better known to the wider population, especially to the local Irish, the definition of a Celt changed. The ridiculous idea of an invasion by a continental group was replaced by a much more vague definition of “Celt,” simply meaning of Irish or Scottish origin. Although the original intent was to disenfranchise, the Irish have taken pride in their new identity. After all, the idea of Celtics did not take off in the popular imagination until the Irish were able to define it for themselves.

What do you think of the article? Let us know below.

[1]John Waddell, “Celts, Celticisation and the Irish Bronze Age,” in Ireland and the Bronze Age, ed. J. Waddell and E. Twohig (Dublin, 1995), 160.

[2]J.P. Mallory and Barra Ó Donnabháin, “The Origins of the Population of Ireland: A Survey of Putative Immigrations in Irish Prehistory and History,” Emania17 (1998): 47.

[3]Barra Ó Donnabháin, “An Appalling Vista? The Celts and the Archeology of Later Prehistoric Ireland,” in New Agendas in Irish Prehistory, ed. A. Desmond (Cork, 2000), 192.

[4]John Collis, “Celtic Myths,” Antiquity71 (1997): 197.

[5]Tomás Ó Carragáin, 2016. "Early Iron Age - The Celts.” Presentation, Boole Lecture Theater.

[6]Ó Carragáin,"Early Iron Age - The Celts.”

[7]John Collis, “Celtic Myths,” 199.

[8]Mallory and Ó Donnabháin, “The Origins of the Population of Ireland,” 61.

[9]Mallory and Ó Donnabháin, “The Origins of the Population of Ireland,” 61.

[10]Ó Carragáin, "Early Iron Age - The Celts.”

[11]Ó Carragáin, "Early Iron Age - The Celts.”

[12]Ó Donnabháin, “An Appalling Vista?” 192.

[13]Ó Carragáin, "Early Iron Age - The Celts.”

[14]Chris Morash, “Celticism: Between Race and Nation,” in Ideology and Ireland in the Nineteenth Century, ed T. Foley and S. Ryder (Dublin, 1998): 192.