The American Civil War (1861-65) saw a breakthrough in various technologies. One of particular importance was the telegraph, a communication technology that had grown greatly in significance in the years before the US Civil War broke out. Here, K.R.T. Quirion starts his three-part series on the importance of the telegraph in the US Civil War by looking at the history of the telegraph globally and in the US before the war broke out.

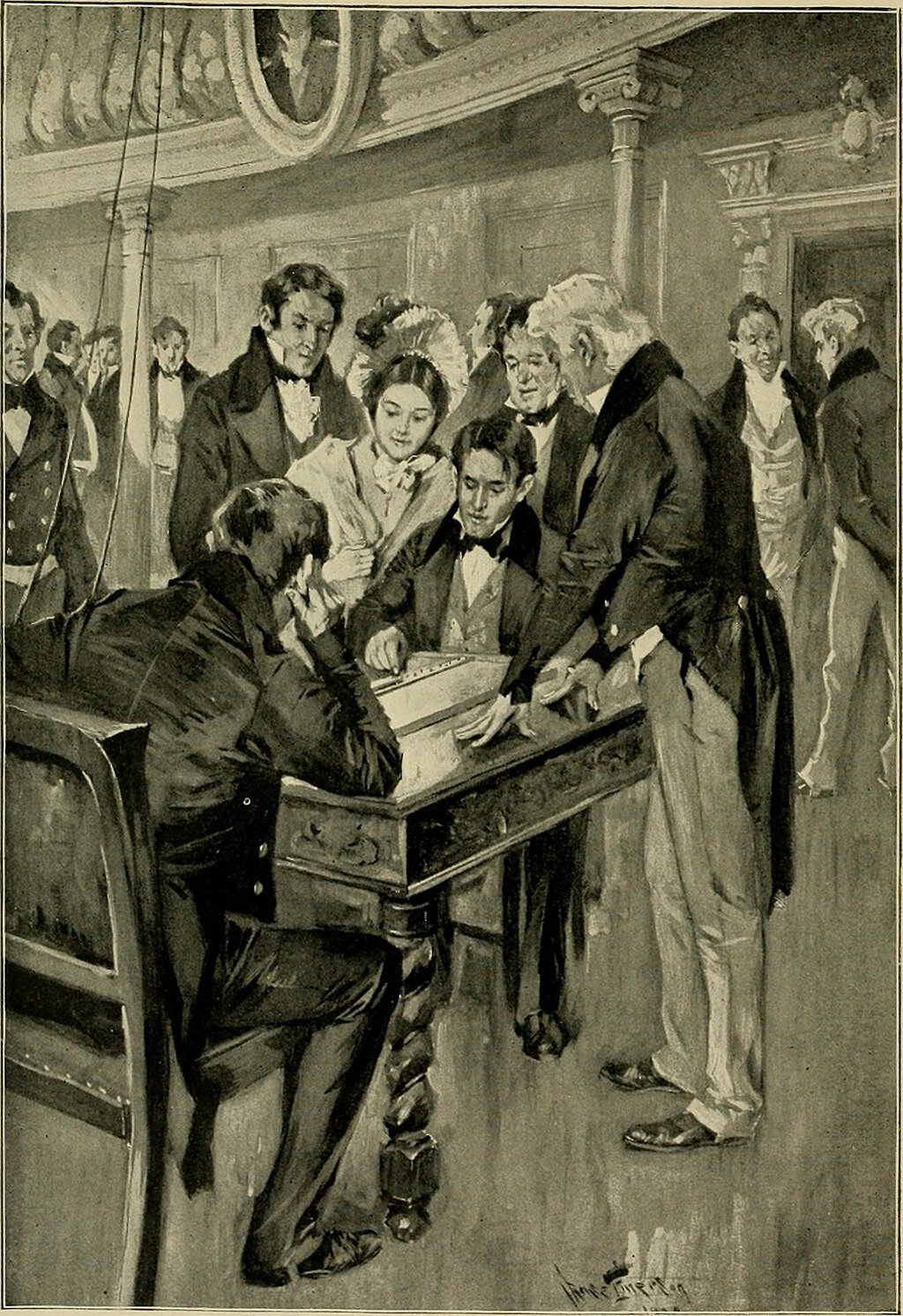

Samuel Morse sending the message ‘What Hath God Wrought’ in 1844. Image available here.

Introduction

The five years of the American Civil War saw the development of hundreds of new technologies. The number of patents approved by the U.S.Patent Office had been steadily increasing before the war. In 1815, the agency issued 173 patents, 1,045 in 1844, and 7,653 in 1860. [1] With the start of the Civil War, the rate of innovation increased so much that at least 15,000 patents were issued every year of the war. [2]

Some of these technologies, like the Gatlin Gun and the Ironclad, were developed specifically for the battlefield; others, such as improvements in transportation and communication were not. Much has already been written on the role that these new technologies played in the Civil War. For instance, that the Minie ball contributed to the high casualty rate has been widely accepted as has the significance of the railroad across the nation’s 1,000-mile battlefront.

This article will focus on the role of the telegraph. Specifically, it will look at how the Union employed this new technology to successfully prosecute the war. It will argue that the telegraph allowed Union commanders, the War Department, and President Lincoln to control huge armies with unprecedented precision across the vast American landscape. This was made possible by thousands of miles of telegraphic wire, sophisticated mobile communication units, and hundreds of trained and dedicated operators. Together, these factors helped to shorten one of the most tragic episodes in American history.

The development of the military telegraphic communication system was a slow and difficult process. Not until the closing years of the war was the Union able to achieve a high level of telegraphic integration within its command structure. In order to appreciate the important role of the telegraph, it is necessary to examine both the development of this infrastructure and how Union leaders sought to integrate it into the military’s command structure.

Military Communication before the Telegraph

Prior to the invention of the telegraph, commanders and their civilian leaders had limited means with which to communicate. The principal method was through writing by couriers or orally by messengers. On the field of battle, other means to communicate were developed to coordinate dispersed units. Smoke signals, trumpets, drums, and flags became important in this regard. In 1794, the French military organized two companies of balloon riding “aeronauts” who used flags to signal their observations of enemy troop movements to friendly units on the ground. [3]

By the 18thcentury, practically every nation had adopted its own signature march which its troops were required to memorize. Amid the chaos of battle, the identity of a distant column of troops could often be identified solely by their marching music. On multiple occasions, resourceful commanders were able to use this to their advantage. One German force in the Thirty Years’ War, obscured its identity by maneuvering to The Scots Marche. According to William Trotter, “Allied (Anglo-Dutch-Austrian) drummers played The French Retreate so convincingly” that part of the French army withdrew from the field during the Battle of Oudenarde in 1708. [4]

In America, the organizational structure of the British Army was closely followed, including field communication by fife and drum. These were further improved during the winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge. There, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben instituted the Continental Army’s first system of drill procedures, which included standardized maneuver and communication signals. These signaling methods “remained virtually unchanged until the invention of the electric telegraph.” [5]

In 1854, Dr. Albert Myer developed a new military signaling system which used a flag and torch combination. This system, known as “wigwag” employed only one flag as opposed to the traditional semaphores signaling, which employed two flags. [6]After appearing before a board of examination in Washington D.C., Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee declared that Dr. Myer’s wigwag “system might be useful as an accessory to… but not as a Substitute for the means now employed to convey intelligence by an Army in the Field, and especially on a Field of Battle.” [7]

Myer’s was authorized to test his new system in combat simulations. In June of 1860, the U.S. Army Signal Corps was created and Dr. Myers was appointed as its sole officer. By 1861, Myer had patented his signal system and was testing it in active combat situations in New Mexico under the command of Col. Thomas T. Fauntleroy. During this same time however, an even more revolutionary communication system was being created.

Invention of the Telegraph

The development of the electric telegraph was the work of many individuals over nearly a span of 80 years. In 1774, the first experiments with electronic signaling were conducted by Georges Louis Le Sage of Geneva. Le Sage’s technique employed twenty-four insulated wires that each represented an individual letter and were connected to a pith ball electroscope. When the desired letter was imputed, the electrical current would excite the respective ball on the other end thereby spelling words letter by letter. [8]

Samuel B. Morse began his work on the telegraph in 1832. Morse’s improved telegraph machine was patented on June 20, 1840. Patent number 1,647 covered the electro telegraph machine itself, Morse’s specialized “code” system, the type set for communicating those symbols and even its accompanying dictionary. His patent also included a “mode for laying the circuit of conductors” needed to operate the telegraph system. [9]

With this new design, the electric telegraph would soon transform the nature of communications. Morse, too poor to test his invention on a large scale, went before Congress in order to request $30,000 with which to construct an appropriate experiment. Wary of spending taxpayer monies on a dead end, Morse’s request was initially rejected by Congress. Despite this, the 1843 Congress approved the expenditure in its “expiring hour” and Morse began the work of constructing a “double (circuit) wire between Washington [D.C.] and Baltimore.”[10]

Finally, in 1844, Morse sent the world's first electric telegraph message across the Washington-Baltimore circuit. [11]He quoted four simple words from Numbers 23:23, “What God hath wrought?” Underlying this dramatic message was the knowledge that the world had entered a new era of communication and connectedness. [12]In 1841, it had taken 110 days for the news of the death of President Harrison to reach Los Angeles, California. [13]By the end of the decade, more than 20,000 miles of telegraph line would tie together the American landscape. This near instant transmission of information forever altered the course of history.

The State of Telegraphic Communications before the Start of the Civil War

Implementation of the telegraph on the battlefield would first occur in Europe during the Crimean War (1854 - 1855). This crude military telegraph system was limited to inter-command center communications. Two years later in India, the English used a system of rollers and carts to deploy miles of telegraph lines that were said to have worked over distances of one hundred miles. [14]The success that the English experienced with the telegraph caught the attention of the German military. Beginning in 1855, they instituted the first telegraph system as a permanent part of their military organization. The French and the Spanish militaries followed soon after.

In America, the telegraph had just over seven years to “develop in peaceful employments” before the start of the Civil War. [15]During that time, thousands of miles of wire were laid in conjunction with the rail lines that were beginning to crisscross the American landscape. Together, these new technologies began to change the pace of American life. Near instant communication and speedy travel “began to insinuate time as a factor into people’s daily lives...” and “…in business thinking.” [16]

Three great companies grew out of America’s growing reliance on telecommunications: the American Telegraph Company, the Western Union Telegraph Company, and the Southwestern Telegraph Company. By 1861, the combination of these three concerns had connected all of the major cities in the Union with the exception of those to San Francisco, California which were not completed until the end of the year. [17]There were more than 50,000 miles of telegraph cable in operation by 1861. [18]Yet, as the country headed toward war, the vast potential of the telegraph had only begun to be realized. Over the following five years, the telegraph would prove itself to be among the most revolutionary inventions of the 19thcentury.

What do you think about the importance of the telegraph in the 19th century? Let us know below.

Now, you can read part 2 on the telegraph in the early years of the US Civil War here and part 3 on the Union’s use of the telegraph in the US Civil War here.

[1]“Civil War and Industrial Expansion, 1860–1897 (Overview),” Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History, 1999, Encyclopedia.com, accessed February 28, 2016.

[2]Ibid.

[3]William R. Plum, The Military Telegraph During the Civil War in the United States, Vol. I (New York, NY: Arno Press, 1974), 16.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Rebecca R. Raines, Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1996), 4.

[6]Ibid., 5.

[7]Ibid., 6.

[8]Plum, The Military Telegraph During the Civil War in the United States, Vol. I,24.

[9]Samuel F.B. Morse, “Improvement in the Mode of Communicating Information by Signals by the Application of Electro-Magnetism,” Patent No. 1,647, United States Patent Office, (June 20, 1840), 1.

[10]Plum, Vol. 1,25.

[11]Don Cambou, Civil War Tech inModern Marvels, (New York, NY: A&E Television Network, 2006).

[12] “First transatlantic telegraph cable completed,” History.com, accessed March 01, 2016.

[13]Arthur K. Peters, Seven Trails West, (New York, NY: Abbeville Press, 1996), 173.

[14]Plum, Vol. I,27.

[15]Ibid., 26.

[16]John E. Clark, Railroads in the Civil War: The Impact of Management on Victory and Defeat, (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2001), 10.

[17]Plum, Vol. I,63.

[18]Cambou.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources:

Bates, David H. Lincoln in the Telegraph Office: Recollections of the United States Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War. New York, NY: D. Appleton-Century Company Inc. (1907).

The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Ed. Roy Basler. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. (1953).

Greely, A.W. “The Military-Telegraph Service.” Signal Corp Association. Accessed May 3, 2016.

http://www.civilwarsignals.org/pages/tele/telegreely/telegreely.html

Morse, Samuel F.B. “Improvement in the Mode of Communicating Information by Signals by the Application of Electro-Magnetism.” Patent No. 1,647. United Stets Patent Office. (June 20, 1840).

O’Brien, John E. Telegraphing in Battle: Reminiscences of the Civil War. Scranton, PA: The Reader Press. (1910).

Plum, William R. The Military Telegraph During the Civil War in the United States, Vol. I & II. New York, NY: Arno Press. (1974).

“War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 Vols.” U.S. War Department. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. (1880–1901).

Secondary Sources:

Cambou, Don. Civil War Tech in Modern Marvels. New York, NY: A&E Television Network. (2006).

“Civil War and Industrial Expansion, 1860–1897 (Overview).” Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. 1999. Encyclopedia.com. Accessed February 28, 2016.

http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3406400169.html

Clark, John E. Railroads in the Civil War: The Impact of Management on Victory and Defeat. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. (2001).

Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative, Vol. 1 Fort Sumter to Perryville. New York, NY: Random House. (1958).

“First transatlantic telegraph cable completed.” History.com. Accessed March 01, 2016. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-transatlantic-telegraph-cable-completed.

Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. (1988).

McPherson, James M. Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. (2001).

Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York, NY: Penguin Books. (2007).

Peters, Arthur K. Seven Trails West. New York, NY: Abbeville Press. (1996).

Raines, Rebecca R. Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Washington D.C.: Center of Military History. (1996).

Wheeler, Tom. Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War. New York, NY: Harper Business. (2007).

Journal Articles:

Farhi, Paul. “How the Civil War gave birth to modern journalism in the nation’s capital.” Washington Post.(March 2, 2012).

https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/how-the-civil-war-gave-birth-to-modern-journalism-in-the-nations-capital/2012/02/24/gIQAIMFpmR_story.html.

O’Brien, J. Emmet. “Telegraphing in Battle.” The Century, Vol. 38, Is. 5 (Sep., 1889). http://www.civilwarsignals.org/pages/tele/teleinbat/teleinbat.html.

Scheips, Paul J. “Union Signal Communications: Innovation and Conflict.” Civil War History, Vol. IX, No. 4 (Dec. 1963).

Trotter, William R. “The Music of War.” HistoryNet. http://www.historynet.com/the-music-of-war.htm.