This three-part series takes on one of America's most important founding fathers, John Adams. John Adams’ contributions to the founding, development, and success of the United States was unrivaled by others of his generation. In this series, Avery Scott examines John Adams’ life and contributions to the United States from three perspectives. First, John Adams the patriot here. Second, John Adams the diplomat. Third, John Adams the Statesman.

Here, Avery looks more closely at John Adams as a diplomat across Europe.

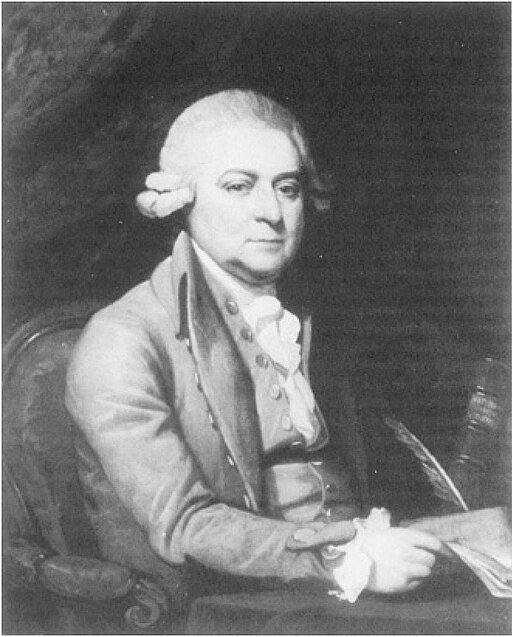

A portrait of John Adams in 1785 (shown here in black and white). By Mather Brown

Introduction

John Adams served his country in the diplomatic service for much of his life. Eventually, becoming the most experienced foreign diplomat in service, he was called upon to negotiate some of the new nation's most difficult situations. Despite Adams future successes, his diplomatic career began with a torrent of failures.

Lord Howe

After the signing of the Declaration of Independence, the war took a turn for the worst with British forces commencing hostilities on New York. The troops under control of General Washington showed their inexperience and lack of discipline when attacked by professional soldiers. Many soldiers ran from their post, deserting the field and in their wake, leaving behind weapons and powder already in short supply. Fortunately, brave Marylander’s under the command of Lord Stirling guarded the retreating army, making a retreat possible - despite suffering heavy casualties.

Washington knew that his men had to reach safety quickly, as he expected a British armanda to arrive shortly to blockade his overwhelmed Army. Gen. Washington brilliantly developed a plan to retreat across the East river under cover of darkness and fog thanks to brave Massachusetts seafarers who conducted the soldiers' safe passage throughout the night. While the defeat was difficult, the escape was a small silver lining to an otherwise dark cloud. Washington saved the bulk of the Army to fight another day, but learned how weak the force was that he was defend the nation. Soon the news of the battle and escape arrived to Congress, as did paroled General John Sullivan bearing news of Admiral Lord Howe’s desire to speak with a delegation from the colonies regarding an “accommodation.” Adams stood firm that no such meeting should occur, however he was overruled by the greater majority of Congress. Ironically, despite his objections, Adams was selected as one of three members who should meet with Howe on Staten Island. The other two members selected were Benjamin Franklin and Edward Rutledge. So on September 11, 1776 the three commissioners met with Admiral Lord Howe to discuss Howe’s proposal of “re-union” of the colonies to their rightful allegiance to the crown. It was here that Adams began a diplomatic career that would change the fate of America.

France

After the meeting with Admiral Lord Howe, which proved to be a worthless endeavor, and the sting of the loss at New York fresh on their mind, Congress began deliberations to find new ways of recruiting and maintaining a professional Army. It quickly became apparent that America was in an untenable position, and needed an ally to assist in winning the war. Specifically, Congress needed an ally with access to men, supplies, and money. The delegates knew France was their best hope to be victorious. Adams was wary of this alliance, and stood firm that it must be purely militaristic in nature, and not entangle America in the future problems of France (a country that spent more time at war than at peace). Seeing France as their best option, Congress appointed Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson commissioners to France with the goal of assisting Silas Deane in negotiating a treaty of alliance. Thomas Jefferson was replaced by Aruthur Lee when Jefferson declined the appointment due to personal reasons.

Adams soon returned home to Braintree, and then back to Baltimore for another session of Congress. It was during this session that Adams was given the most dispiriting news of the war yet. Washington’s troops were bested by Howe’s forces at Brandywine Creek. Who could then march, unabated, the short distance to Philadelphia - routing Congress. Fleeing to York, Congress convened but many members, including Adams, soon departed for home. After enjoying the comforts of home for some weeks, Adams traveled to represent a client in his capacity as a lawyer. During his absence, Abigail received Adams commission to serve with Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee in France. He was being called to serve in place of Silas Deane who was recalled to answer to Congress for his actions as commissioner. Abigail, upon reading the commission, was furious with Congress and their attempt to make her life “one continued scene of anxiety and apprehension.” Despite her effort, he quickly accepted the appointment as he felt it his public duty. Adams would depart for France leaving behind his entire family - except John Quincy who would journey with his father. In secrecy, to avoid spies or attack, father and son departed their home waters aboard the Boston. Captain Samuel Tucker was to be responsible for transporting the Adams’ safely to France. Tucker accomplished this mission, albeit not without some difficulty on the way. Namely, the capture of the British cruiser Martha. But after six weeks and four days aboard ship, Adams was rowed ashore, leaving the Boston behind, and beginning what would become one of the greatest diplomatic careers in the nation's history.

Immediately after Adams arrival, he began to be introduced to French society by Benjamin Franklin. Franklin, being the most popular American in France, had many friends that he advised Adams befriend as well. Adams quickly became enamored with the culture and excitedly wrote Abigail regarding the experiences thus far. However, Adams also met Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, the King’s Foreign Minister, who would become a thorn in the side of Adams’ diplomatic hopes. However, the first problem Adams encountered had nothing to do with diplomacy or the French. Rather, it was the ongoing turbulence between Franklin and Arthur Lee, which led both men to complain of the other to Adams in private. Despite personal differences, the men shared the common goal of an alliance with France. And the first step to this was to introduce the new Minister to King Louis XVI. In which Adams was struck by the importance of King Louis on the future of the Nation.Adams spent much of his time in France feeling as though he was accomplishing little, because the treaty of alliance he was sent to negotiate was already agreed upon prior to his arrival. And the Comte de Vergennes seemed disinterested at best or unwilling at worst to do anything additional to help America. Because of this, he spent the remainder of his first stay in Paris struggling with his fellow commissioners, the Comte de Vergennes, and frustration from Abigail regarding his continued absence. However, Abigail need not worry long, as Adams soon received the news that Franklin was appointed by Congress to be the sole Minister to Paris, with no direct instructions being given to Adams as to future assignments. Deeply hurt by the betrayal, Adams planned to sail home.

Home Again

Adams, despite frustration at Congress for the lack of communication, was deeply relieved to be home with the family he loved and his farm. He would not have much time to enjoy retirement as he was soon selected as a delegate to the Massachusetts state convention in order to form a state constitution. Once Adams completed his work for the state convention, and the new constitution was ratified, Adams was called back to Paris to serve as a Minister Plenipotentiary to negotiate treaties of peace with Great Britain. Adams was frustrated at the way he was treated by Congress, with Henry Laurens writing an apology to Adams stating he was “dismissed without censure or applause.” So as it were, Adams now set sail again to France, John Quincy in tow as he was before, but with the addition of his other son, Charles.

Holland

His time in Paris began with the first of many battles with Vergennes regardings his commision, and the appropriate time to reveal his intentions. This would not be the final battle between the two, as Vergennes eventually attempted to effect the recall of Adams. Even going so far as to employ Franklin in the attempt. Despite the treachery, it became a turning point in Adams’ career, as this is when he made the decision to visit Holland in an attempt to gain financial assistance. Adams trip to Holland was one of “militia diplomacy” in which he bent the rules of his new nation, and the customs long followed by all nations to affect his change. He had not been called to do so by Congress, but instead went on his own free will. Eventually, Congress officially voted for Adams to serve in this role. Which proved vital as Adams was very successful with the Dutch, with the Hague voting to recognize him as the Foreign Minister to the Netherlands on April 19, 1782, and the independence of America was also recognized. Eventually, trips to Holland would lead to a multitude of Dutch loans to America that allowed for the continuance of the war effort, and the ability to pay the balance of prior loans, and began to build American credit abroad. Additionally, on October 8, 1782, Adams negotiated, and signed, a Treaty of Commerce with the Netherlands.

Treaty with Britain

After negotiating the Dutch treaty, Adams was dispatched back to Paris for final peace negotiations. Unfortunately for Adams, he lost his appointment as sole Minister to France following the letters to congress from the Comte de Vergennes and Franklin. However, he was still on the team of diplomats responsible for such negotiations. This team included Adams, Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay, and Henry Laurens (Jefferson being absent for the time, and Laurens being in the Tower of London). Adams was in little rush to attend the negotiations, and ensured that he wrapped up all open business at the Hague prior to leaving - even doing some sightseeing on the way. Upon his arrival in Paris he was dejected to learn of Congress secret instructions to the negotiators to only push for concessions approved by the French government. Even Franklin, the member most beholden to the French, found this to be an untenable position to negotiate from. Eventually agreeing with the other delegates that they would proceed contrary to Congress instruction, and strike the best deal possible with Britain without prior approval from France. The men worked well together, gaining land for the US and reaching peace terms the British found agreeable. It was only on the point of private debts that the commissioners deferred. Jay and Franklin felt that private debt agreements between Americans and British merchants should be forgiven due to the damage the British inflicted upon their former colonies. However, Adams strongly argued, eventually winning, that private debts should be paid notwithstanding injuries from war. This was, however, more of a personal victory than a practical one. Because few individuals would make much attempt to repay the debts, and both state and national congress’ would do little to enforce it.

Adams' final stand came on the rights of American fishermen to fish in the waters off Nova Scotia. Adams was a Massachusetts man, and though not a seafaring man himself, grew up watching the value of cod and other fish to his region's economy - refusing the British to take away this right.

A preliminary treaty of peace was signed with the British on November 30, 1782. With the official treaty being ratified on September 3, 1783 thus ending hostilities. Following the treaty, in August of 1784 - Abigail joined her “dear Mr. Adams” in Paris. After a blissful reunion in Paris, Adams was eventually named the Ambassador to the Court of St. James. The goal of this post being to resolve outstanding issues between America and Britain following the Treaty of Paris. With sadness, Abigail and John left Paris to assume their new post as the first minister from America to King George III. Adams' diplomatic career would continue for many years following the signing of the Treaty of Paris and his call to London. However, in the years following his arrival to France, Adams proved that he was no longer an inexperienced diplomat, and had now become a statesman….

What do you think of John Adams as a diplomat? Let us know below.

Now read Avery’s article on the role of privateers in the American Revolution here.