The firing on Fort Sumter was the immediate action that started the Civil War. Once the Confederates under PGT Beauregard fired on US Federal property, a line had been crossed and a rebellion had begun. At issue was whether federal property in a state that seceded was now property of the new government.

Charleston SC was the most important port on the Southeast coast. The harbor was defended by three federal forts: Sumter; Castle Pinckney, one mile off the city’s Battery; and heavily armed Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island.

Here, Lloyd W Klein looks at the beginning of the U.S. Civil War.

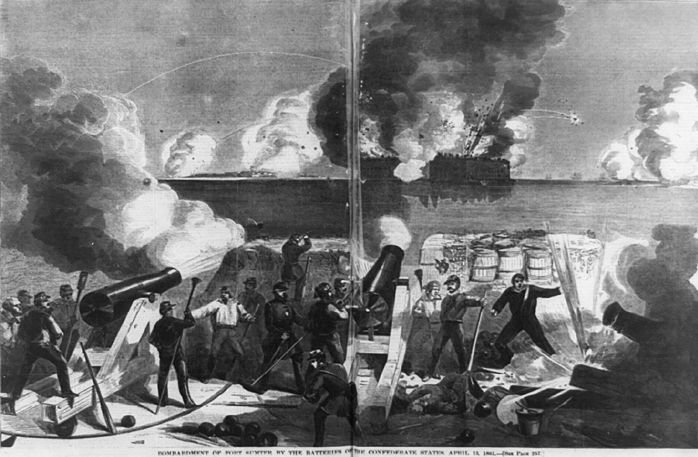

The attack on Fort Sumter by the Confederacy.

The Construction and Deed to the Fort

The island in Charleston harbor on which Fort Sumter is built was originally just a sand bar. In 1827, engineers performed measurements of the depths and concluded that it was a suitable location for a fort. Construction began in 1829. Seventy thousand tons of granite was transported from New England to build up an essentially artificial island. By 1834, a timber foundation that was several feet beneath the water had been laid. The fort was built in the center of the channel to dominate the entrance to the harbor. Along with the shore batteries at Forts Moultrie, Wagner, and Gregg, the idea was to cover the harbor from invaders. The brick fort was designed to be five-sided, 170 to 190 feet long, with walls five feet thick, standing 50 feet over the low tide mark, and to house 650 men and 135 guns in three tiers of gun emplacements. The majority of the gun emplacements faced out to sea, to cover the entrance to the harbor (not facing the city). Construction dragged on because of title issues, and then problems arose with funding such a large and technically challenging project. Unpleasant weather and disease made it worse. The exterior was finished but the interior and armaments were never completed. On December 17, 1836, South Carolina officially ceded all "right, title and, claim" to the site of Fort Sumter to the United States Government. For these reasons, at the time of the bombardment, not only was this a federal fort, but also it was legally land ceded by the state of South Carolina.

Fort Sumter was covered by a separate cession of land to the United States by the state of South Carolina, and covered in this resolution, passed by the South Carolina legislature in December of 1836.

Reports and Resolutions of the General assembly, Page 115, here: https://www.carolana.com/SC/Legislators/Documents/Reports_and_Resolutions_of_the_General_Assembly_of_South_Carolina_1836.pdf

This resolution was made in response to a private SC citizen claiming ownership, which was denied. There can be no clearer statement that Fort Sumter had been ceded to the US Government by the state of SC.

https://studycivilwar.wordpress.com/2013/04/14/who-owned-fort-sumter/comment-page-1/#comments

In 1805, a prior land resolution of the SC legislature turning over all of the forts in the harbor to the US Government was made. Sumter did not exist at that time, so arguably it didn’t apply, although the language would be inclusive. It can be found on pages 501-502 here: https://books.google.com/books?id=S7E4AAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

South Carolina had freely ceded property in Charleston Harbor to the federal Government in 1805, upon the express condition that "the United States... within three years... repair the fortifications now existing thereon or build such other forts or fortifications as may be deemed most expedient by the Executive of the United States on the same, and keep a garrison or garrisons therein." Failure to comply with this condition on the part of the Government would render "this grant or cession... void and of no effect." Hence, continued development was a condition, which did occur in spurts.

The Crisis Begins

On December 26, 1860, only six days after South Carolina seceded from the Union, Major Robert Anderson abandoned the indefensible Fort Moultrie, spiking its large guns, burning its gun carriages, and taking its smaller cannon with him. He secretly relocated companies E and H (127 men, 13 of them musicians) of the 1st U.S. Artillery to Fort Sumter on his own initiative, without orders from his superiors, because it could not be defended from a land invasion. The fort was still only partially built and fewer than half of the cannons that should have been available were in place.

In a letter delivered January 31, 1861, South Carolina Governor Francis W Pickens demanded that President Buchanan surrender Fort Sumter because "I regard that possession is not consistent with the dignity or safety of the State of South Carolina." Over the next few months repeated calls for the evacuation of Fort Sumter from the government of South Carolina were ignored.

In February 1861 South Carolina's Attorney General, Isaac Hayne sent a letter to the U.S. Secretary of War, John Holt about their intent to take possession of Fort Sumter and wished to negotiate monetary compensation threatening that if the United States refused to vacate, then force would be used to seize it. Holt responded that the United States' interest in Sumter is not that of a proprietor but that of a sovereign which "has absolute jurisdiction over the fort and the soil on which it stands. This jurisdiction consists in the authority to 'exercise exclusive legislation' over the property referred to. and said "the President is, however, relieved from the necessity of further pursuing this inquiry by the fact that, whatever may be the claim of South Carolina to this fort, he has no constitutional power to cede or surrender it. The property of the United States has been acquired by force of public law, and can only be disposed of under the same solemn sanctions. The President, as the head of the executive branch of the Government only, can no more sell and transfer Fort Sumter to South Carolina than he can sell and convey the Capitol of the United States to Maryland, or to any other State or individual seeking to possess it."

Realizing that the garrison at Fort Sumter was undermanned and undersupplied, General Winfield Scott, the General-in-Chief of the US Army, sent the Star of the West to reinforce Anderson. On January 9, 1861, several weeks after South Carolina had seceded from the United States but before other states had done so to form the Confederacy, Star of the West arrived at Charleston Harbor to resupply troops and supplies to the garrison at Fort Sumter. The ship was fired upon by cadets from the Citadel Academy and was hit three times. Although Star of the West suffered no major damage, her captain, John McGowan, considered it to be too dangerous to continue and left the harbor. The mission was abandoned, and Star of the West headed for her home port of New York Harbor. Even this minimal attempt at strengthening the fort was resisted (Mc266). President Buchanan had been lukewarm about defending Charleston harbor in the first place and had seriously considered succumbing to southern popular opinion and ordering the defenders back to the indefensible Fort Moultrie. He had only agreed to this single ship expedition after a cabinet shake-up bringing hardliners Edwin Stanton and Jeremiah Black to his advisory group. Yet in response to this attack on a federal ship, which might itself have triggered the war, he did nothing.

Over the next few months, Jefferson Davis was named president of the Confederacy and Abraham Lincoln inaugurated as US president. Confederate Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard was sent to lead the Confederate forces in Charleston, where his command included several thousand state militia and a few dozen seacoast guns and mortars. Davis sent commissioners to Washington to negotiate transfer of the fort. Anderson prepared the fort for battle as best as possible: remarkably, of the 60 guns placed in the fort, only 6 were capable of being turned around to face the town.

Lincoln searched for a political solution for the next 6 weeks. Most of his cabinet, including Scott, advised that he pull the troops out of Fort Sumter because it was indefensible. William Seward, Secretary of State, Simon P. Cameron, Secretary of War, and Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy favored withdrawal. Supporting the fort would require a military force comprised of both army and navy units way beyond what existed. But Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury and Montgomery Blair, the Postmaster General, argued that surrender would diminish morale and would lead to official recognition of the Confederacy. Only Blair opposed the withdrawal firmly because it would convince the rebels that the US administration lacked determination and firmness, would dishearten the Southern Unionists and push the foreign countries to recognize the Confederacy de facto. Moreover, the northern media called on Lincoln to make good his inaugural promise to defend federal property. Lincoln concluded that if the Union troops evacuated Fort Sumter, secession would be a fait accompli.

Lincoln was aware that a large - scale attempt to supply Fort Sumter by firing warships would result in the North as aggressor. It would unite the South and make Lincoln accountable for breaking out a war. Blair provided a person who would find a solution to the problem: Gustavus V. Fox. Fox suggested to supply Fort Sumter via some motorized barges while the US warships, off shore, would intervene only the Confederate guns would fire on the barges. Thus, he sent supplies only, while the warships would be ready to intervene if the Confederate guns had fired on the flotilla. If the Confederates had fired on the unarmed motorized barges hauling supplies only, they would be accountable for having attacked a humanitarian relief mission. At a cabinet meeting on March 28, 1861, the decision was made to send a small flotilla of vessels loaded with supplies. Realizing that Anderson's command would run out of food by April 15, 1861, President Lincoln ordered a fleet of ships, under the command of Gustavus V. Fox, to attempt entry into Charleston Harbor and supply Fort Sumter. It was plainly recognized that this small group of ships could not enter the harbor by surprise and would not be able to reach the fort unless the South Carolina batteries allowed their unfettered passage. (https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2011/march/sumter-conundrum). Lincoln told Pickens the ships were on their way for re-supply.

Pickens contacted Robert Toombs, the CSA Secretary of State, Robert Toombs, who advised Davis that he was being set up by Lincoln and tricked into starting the war. Nevertheless, a Confederate cabinet meeting on April 9 endorsed Davis’s order to Beauregard to reduce the fort before its arrival. Fearing that a lack of action would revive Southern Unionism, Davis decided the Federal presence had to go, that is, Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard was authorized to use the force to surrender Fort Sumter. Retrospectively, Davis would have been wise to have taken Toombs’ advice. As a fort built to keep out ships, it served no purpose at that moment other than to allow Lincoln to use it as bait to trick the Confederates into starting the war, handing Lincoln reason/pretext and to claim the Confederates fired first. But Davis in fact wanted war; it was the only possible way to convince the ambivalent Upper South and border states to secede and join the CSA. Davis had considered attacking Fort Pickens instead, but Braxton Bragg correctly objected because Pickens would have been tough to attack by amphibious warfare and, unlike Sumter, had a secure sea lifeline.

On April 6, 1861, the first ships began to set sail for their rendezvous off the Charleston Bar. The ships assigned were the steam sloops-of-war USS Pawnee and USS Powhatan, transporting motorized launches and about 300 sailors; the USS Pocahontas, Revenue Cutter USRC Harriet Lane, and the steamer Baltic transporting about 200 troops, composed of companies C and D of the 2nd U.S. Artillery; and three hired tugboats with added protection against small arms fire to be used to tow troop and supply barges directly to Fort Sumter. However, the Pocahontas never did make it due to multiple countermanding orders. The first to arrive was Harriet Lane, on the evening of April 11, 1861.

Events Leading to the Bombardment

Also on April 11, Beauregard sent three officers to demand the surrender of the fort: Senator/Colonel James Chesnut, Jr., Captain Stephen D. Lee (later general), and Lieutenant A. R. Chisolm. Anderson declined, and the aides returned to report to Beauregard. After Beauregard had consulted the Confederate Secretary of War, Leroy Walker, he sent the aides back to the fort and authorized Chesnut to decide whether the fort should be taken by force. Anderson, stalling for time, waited until 3 AM April 12 to tell them he would not leave the fort. They then returned to Fort Johnson where Chesnut ordered the firing to begin. So it was that on April 12, 1861 at 4:30 AM, the Civil War began when Confederate batteries opened on the fort. Although Edmund Ruffin, the noted Virginian agronomist and secessionist, claimed that he fired the first shot on Fort Sumter, and did, in fact, fire a signal shot, Lieutenant Henry S. Farley, commanding a battery of two 10-inch siege mortars on James Island actually fired the first shot at 4:30 a.m. No attempt was made by the Union to return the fire for more than two hours because there were no fuses for their explosive shells, which means that they could not explode. Only solid iron balls could be used. At about 7:00 a.m., Captain Abner Doubleday, the fort's second in command, was given the honor of firing the Union's first shot, in defense of the fort. Although he did not invent baseball as the Mills Commission erroneously concluded, in every other way, his life was eventful and fulfilling.

During the bombardment, according to the diary of Mary Chesnut, the Senator’s wife, and other accounts, Charleston residents along what is now known as The Battery, sat on balconies drinking salutes to the start of the hostilities.

The bombardment lasted for 34 hours. The Union return fire was intentionally slow to conserve its ammunition. The next morning, the fort was surrendered. During the attack, the Union colors fell. Lt. Norman J. Hall risked his life to put them back up, burning off his eyebrows permanently. A Confederate soldier bled to death having been wounded by a misfiring cannon. One Union soldier died and another was mortally wounded during the 47th shot of a 100-shot salute, given after the surrender. For this reason, the salute was shortened to 50 shots.

PGT Beauregard

PGT Beauregard was the perfect combination of military engineer and charismatic Southern leader needed at that time and place. It is highly suggestive that a man of Beauregard’s accomplishments was there at Charleston – before a war had started. Its also interesting that the South Carolina militia had been called out and that they had cannonballs with fuses but the US Army in the fort did not. These and other factors demonstrate that the new CSA was prepared for a battle. The South Carolina Militia had been in position for months. They were there when Citadel cadets fired on the Star of the West on January 9, 1861. They were on duty the previous December when Anderson abandoned Fort Moultrie for Sumter.

Beauregard was the first Confederate general officer, appointed a brigadier general in the Provisional Army of the Confederate States on March 1, 1861. His brother in law, James Slidell, was instrumental in convincing Davis to make this appointment. To me, the idea that the Union escalated violence to provoke the war is odd considering that the CSA had created an army at least 6 weeks before firing on Sumter. After the Mexican War, during which he contributed at least as much as Captain Robert E Lee did in terms of reconnaissance and strategy, his positions involved engineering in ports so he was the perfect man for this mission. He had recently been named superintendent of West Point January 23 1861, but these orders were revoked by the Federal Government 5 days later when Louisiana seceded. He returned to New Orleans with the hopes of being named commander of the Louisiana state army. On July 21, he was promoted to full general in the Confederate Army, one of only seven appointed to that rank; his date of rank made him the fifth most senior general, behind Samuel Cooper, Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and Joseph E. Johnston. Beauregard was honored in the South for its first victory. He was ordered to direct the troops at Bull Run.

Anderson had been Beauregard’s artillery instructor at West Point in 1837, and Beauregard was serving as superintendent there until secession. Anderson told Washington that Beauregard would guarantee that South Carolina's actions be exercised with "skill and sound judgment." Beauregard wrote to the Confederate government that Anderson was a "most gallant officer". He sent several cases of fine brandy and whiskey and boxes of cigars to Anderson and his officers at Sumter, but Anderson ordered that the gifts be returned.

Aftermath

The state legislature appointed Braxton Bragg on February 20, 1861.Bragg had been a colonel in the Louisiana militia. Aware that Beauregard might resent him, Bragg offered him the rank of colonel. Instead Beauregard enrolled as a private in the "Orleans Guards", a battalion of French Creole aristocrats. At the same time, he communicated with Slidell and the newly chosen President Davis, angling for a senior position in the new Confederate States Army. Rumors that Beauregard would be placed in charge of the entire Army infuriated Bragg. Their personal animosity was one of the subthemes of the western theater for the next 4 years.

Anderson’s valor and commitment to duty was recognized in the Union. The Fort Sumter Flag became a popular patriotic symbol after Major Anderson returned North with it. The flag is still displayed in the fort's museum. The Star of the West took all the garrison members to New York City. There they were welcomed and honored with a parade on Broadway.

What do you think of the events at Fort Sumter? Let us know below.

Now, if you missed it, read Lloyd’s piece on how the Confederacy funded its war effort here.