During the Franco-Prussian War, Paris was under siege, cut off from communication, and facing dwindling supplies. In a daring move, Parisians took to the skies with gas-filled balloons to carry mail, people, and news across enemy lines. These flights, though dangerous and often unpredictable, became a vital lifeline and stand as one of the most innovative uses of aviation in wartime. This article delves into the bold balloon post operation and its significance during the Siege of Paris.

Richard Clements explains.

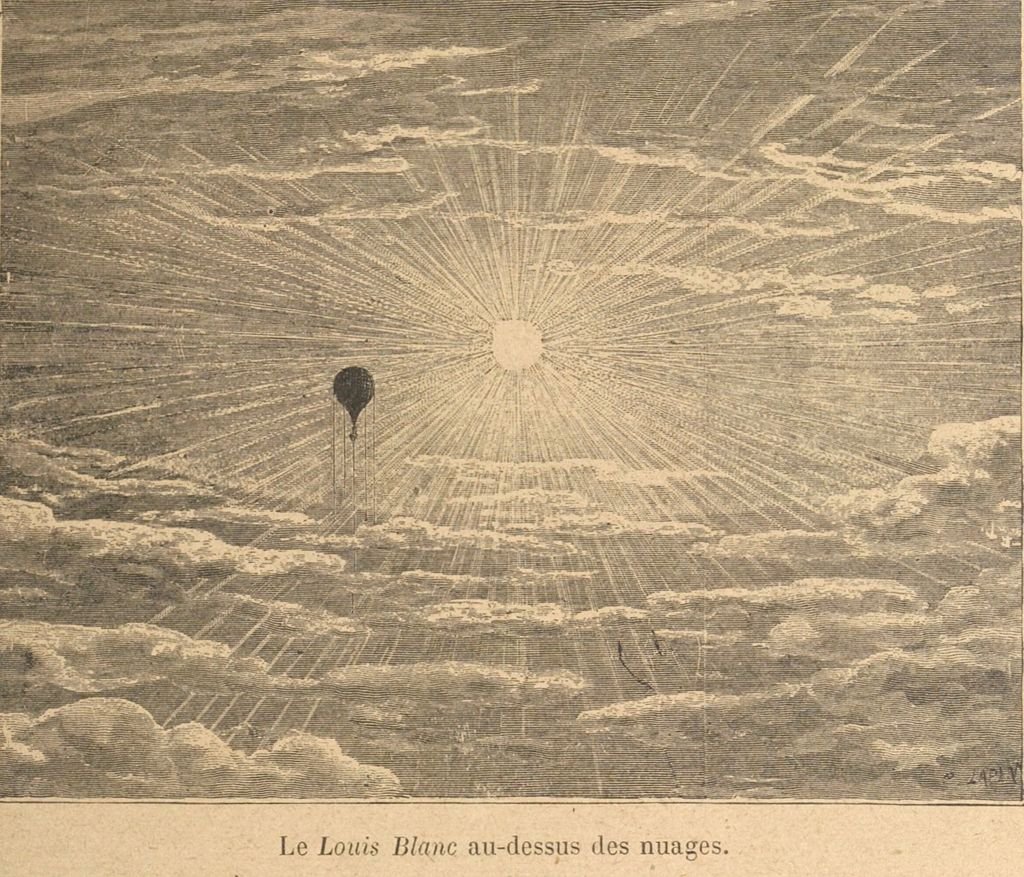

The Louis Blanc, piloted by Eugène Farcot. Part of the Balloon Post.

Historical Context: The Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Paris

The Franco-Prussian War began in 1870, with Prussian forces quickly overwhelming French defenses. By September, Paris was completely encircled by Prussian troops, cutting off communication with the rest of the country. The Government of National Defense, formed by republican deputies in Paris, desperately needed to maintain contact with unoccupied France and the French government-in-exile in Tours. To address this, the Parisians turned to an ingenious solution: balloon post.

The Birth of the Balloon Post

With telegraph lines cut and roads blocked, the idea of using balloons to carry mail and messages out of Paris arose out of sheer necessity. The first balloon was launched on September 23, 1870, by Jules Duruof, a professional balloonist. His flight carried critical dispatches, and the success of this mission led to the establishment of regular balloon services. Eyewitness accounts from Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (known as Nadar) describe the public’s awe and anticipation as they watched the first balloons ascend, hoping for safe passage.

Balloon Construction and Design

Most of the balloons used during the siege were gas-filled, typically with hydrogen, which was produced by decomposing zinc and sulfuric acid. These balloons were usually made from silk or rubber and measured 26 to 33 feet in diameter, capable of carrying between 440 and 1,100 pounds of cargo, including mail, newspapers, and sometimes passengers.

While hot air balloons (dirigibles) were experimented with during this period, they were less reliable than their gas-filled counterparts and mainly used for shorter flights. The hydrogen-filled balloons, on the other hand, were much more buoyant and suited for long-distance travel.

Operational Details: Launch Sites and Flight Paths

Balloon flights were launched from various locations within Paris, such as the Gare d'Orléans. Pilots relied on wind direction to steer their balloons, as navigation tools were rudimentary. The unpredictability of balloon flight meant pilots often found themselves landing far from their intended destinations.

For instance, Le Jacquard was famously blown off course and landed in Norway, an event that caused quite a stir given the distance. Similarly, L'Archimède, piloted by naval officer Jules Buffet, flew north and crossed over Belgian and Dutch territory, eventually landing near the Belgian-Dutch border. Buffet later recounted the exhilarating flight, describing how Paris slowly disappeared from view as they rose to 6,500 feet at night, while fires and landmarks lit their way.

Cargo and Passengers

The main purpose of the balloon post was to carry mail, and by the end of the siege, more than two million letters had been sent out of Paris. In addition to mail, government dispatches, newspapers, and even homing pigeons were transported via these balloons. Some balloons also carried passengers, including government officials who needed to escape Paris.

The most famous passenger was Léon Gambetta, the French Minister of the Interior, who escaped Paris by balloon in October 1870. Gambetta’s flight was crucial, as it allowed him to coordinate resistance efforts from outside the besieged city, boosting the morale of the French population.

Successes and Failures

While many balloon flights were successful, some faced dire consequences. Of the 67 balloons launched during the siege, several failed to reach their intended destinations. Some were intercepted by Prussian forces, while others were lost to bad weather or navigational issues. For example, one balloon that tried to land near Mechelen in Belgium was startled by celebratory gunfire, causing the pilot to abort the landing, fearing it was enemy fire.

Despite these challenges, the operation was a tremendous success overall, both in terms of communication and morale. The sight of a balloon rising above the city brought hope to the people of Paris, symbolizing that they were still connected to the outside world.

Retrieving Balloons and Cargo

Once the balloons landed in friendly territory, their cargo of letters and dispatches had to be retrieved, often by locals. For example, after L'Archimède landed in Belgium, local peasants helped Jules Buffet deflate the balloon and recover the letters. The letters and dispatches were then forwarded through regular postal services, ensuring their delivery to recipients across unoccupied France.

The retrieval process wasn’t without risk. In one instance, a balloon’s descent was complicated by local villagers smoking pipes near the hydrogen-filled balloon. Such incidents highlight the unpredictability of balloon landings and the challenges of safely recovering valuable cargo.

The Impact on the Siege

The balloon post played a vital role in maintaining the morale of Parisians during the siege. Knowing their letters and dispatches were reaching the outside world reassured them that they hadn’t been forgotten. Additionally, the balloon post allowed the French government to coordinate military efforts from outside Paris, although communication was one-way, as nothing could be sent back into the city.

Legacy and Historical Significance

The use of balloons during the Siege of Paris marked a key moment in the history of aviation and military communication. The success of gas-filled balloon flights demonstrated the potential of air transport for carrying messages during times of conflict. The balloon post of the siege became a cultural symbol of French resilience and ingenuity, inspiring numerous depictions in newspapers, paintings, and books.

Conclusion

The balloon post of the Siege of Paris stands as a remarkable achievement of innovation and perseverance during a time of extreme hardship. While most of the balloons were gas-filled and expertly crafted for long-distance travel, the occasional use of hot air balloons showed the broad range of experimentation at play. Each flight, whether successful or facing challenges, carried with it the hopes of a city under siege, forever cementing its place in aviation history.

The site has been offering a wide variety of high-quality, free history content since 2012. If you’d like to say ‘thank you’ and help us with site running costs, please consider donating here.

References

Aubry, Octave. The Siege of Paris: 1870-1871. Macmillan, 1933.

Boyle, Andrew. Flights of Fancy: The Balloon Post During the Franco-Prussian War. Military History Press, 1971.

Lachouque, Henry. The French Army and the Franco-Prussian War. Praeger, 1968.

Marsden, William. "Balloon Post: A Pioneering Aviation Feat." History Today, vol. 22, no. 4, 1972.

Nadar, Gaspard-Félix. My Life in the Air. Oxford University Press, 1899.

Rickards, Colin. Aviation Before the Airplane: Paris Balloons of 1870. Oxford University Press, 1980.

Schwartz, Paul. "Balloons over Paris: The Role of Aviation in the Franco-Prussian War." Journal of Military History, vol. 53, no. 3, 1989.

Watson, Charles. The Balloons of Paris: A Forgotten History of Siege Warfare. HarperCollins, 1995.