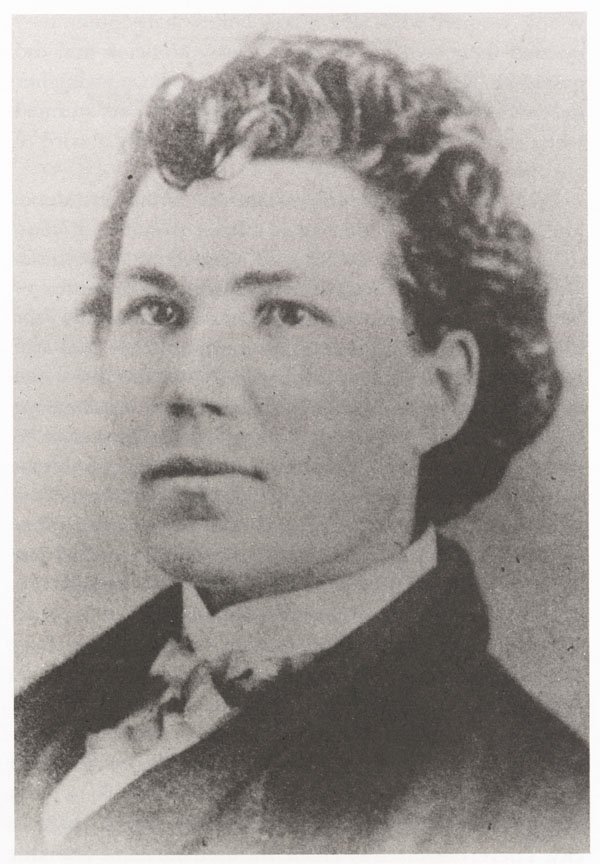

Sarah Emma Edmonds (married name Seelye), a woman who who fought as a man during the US Civil War.

In schools and class textbooks, the Civil War is usually taught as strictly a southern struggle. Certainly, major battles like Vicksburg, Bull Run, the siege of Petersburg and others occurred below the Mason-Dixon line. But we forget that when major conflicts erupt, the struggle and damage can extend well beyond borders and the lines on a map.

Widespread

Few realize that the Civil War nearly ignited an international conflict because of the keen interest of Great Britain and other European powers. In the last months of the war, the South was desperate to ignite an incident that would draw England and other countries into the fray.

The Confederacy sent spies to the northern border with British Canada, from Halifax to Detroit. The most audacious of such plans was to seize the U.S.S. Michigan, the lone Union warship left on the Great Lakes in 1864. (Similar vessels were utilized to blockade the South.)

An unlikely pair – John Yates Beall and Bennet Burley – headed the rebel effort to capture the Michigan. Born in Jefferson County, West Virginia, Beall was a loyal Southerner and had studied law at the University of Virginia. Along the way, he appears to have crossed paths with John Wilkes Booth, who, of course, would later assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

Burley was Beall’s partner in the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. From Glasgow, Scotland, Burley was a soldier of fortune -- joining the fight for the thrill of it. Unlike Beall, he would survive the war, escaping back to the United Kingdom and become a celebrated foreign correspondent for The Daily Telegraph in London.

(Beall and Burley are mentioned briefly in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals and Carl Sandburg’s Abraham Lincoln: The War Years.)

And what would have happened if Beall and Burley had seized the iron-hulled Michigan, with its 30-pounder parrot rifle, half-dozen howitzers and additional firepower? They first planned to free Confederate prisoners on Johnson’s Island near Sandusky, Ohio. These POWs included more than 20 rebel generals.

From there, with no opposing warships in the region, it would have been easy to bombard Cleveland, Buffalo, and other targets along the southern shore of Lake Erie. All of this was planned to unfold shortly before the presidential election. Even though Lincoln handily regained office (212-21 in the electoral college), in the weeks before the vote a Republican victory was far from a foregone conclusion. The nation had been at war since spring of 1861, and many were tired of the long struggle. Lincoln and members of his cabinet feared that he might lose to challenger George McClellan due to war fatigue. This result could have led to the formation of a separate nation, the Confederate States of America.

The role of women

Though often overlooked, women played important roles on both sides of the Civil War, especially when it came to espionage. Elizabeth Van Lew was a member of Richmond high society and appeared to be a loyal Confederate. Yet she gathered information from the rebel capital and sent it across the lines to Ulysses Grant and the Union command by using her servants as couriers.

Actress Pauline Cushman was a Union spy and was in uniform by the end of the war. She was buried with full military honors at the Presidio National Cemetery in San Francisco in 1893. “Union Spy,” reads her simple gravestone.

In function and treachery, Rose O’Neal Greenhow was the mirror image of Richmond’s Van Lew. A longtime fixture in Washington, she was a staunch supporter of the Confederacy and stayed in D.C. when the war broke out, sending valuable information to the rebels. Confederate President Jefferson Davis credited information she supplied for the South winning the first Battle of Bull Run.

Then there’s Belle Boyd, nicknamed the “Cleopatra of the Secession.” She was arrested a half-dozen times for sending military secrets to the south. Eventually, Boyd was banished to Canada and became a well-known actress after the war.

While both sides forbade women from serving in the combat units, that didn’t stop many on both sides from joining combat units in disguise. According to the National Archives, for example, Sarah Edmonds Seelye (originally Sarah Emma Edmonds) served two years in the Second Michigan Infantry under the pseudonym Franklin Thompson. She eventually earned a military pension.

When we reach the fringes of public record, novels can sometimes lead us to a better understanding of what happened and what was at stake. When I began Rebel Falls, I decided I wanted my protagonist, the one who would seek to outwit the rebel spies Beall and Burley, to be a woman. This was partly because I needed a strong connection with the Seward Family. During the Civil War, Secretary of State William Seward was the most powerful man in the North after President Lincoln. Seward’s daughter, Fanny, was one of his closest confidants. So how to move inside that family circle? How about with a character named Rory Chase, a childhood friend of Fanny’s?

Rory is a composite of women who knew Fanny in Auburn, New York, where the family home still stands, as well as in Washington, where the Sewards were center stage during the war years.

Here again, the historical record can be a great starting point. After the war, Fanny Seward died of tuberculosis and was buried with other family members at Auburn’s Fort Hill Cemetery. Soon afterward family friend Olive Risley began to accompany Secretary Seward on his travels. To quell gossip (there was a 43-year difference in their ages), the politician eventually adopted her. A statue of Olive Risley Seward was erected near Capitol Hill in Washington in 1971. My goal with Rebel Falls was to have Rory Chase be emblematic of the resourceful, ambitious women who fought and spied for both sides during the Civil War.

Conclusion

Place and participants. Even with a conflict that has been written about as much as the war between the North and South, such important factors and characters can be overlooked. No wonder Ken Burns calls this clash “our most complicated of wars.”

In focusing upon what took place along our northern border and how women played a key role, I’ve not only tried to tell a forgotten story, but deliver a bit more clarity as well. Only by considering more factors of our nation’s history, hearing about all the factors of the Civil War, can we better understand what occurred and determine how best to move forward.

Tim Wendel is the author 16 books, most recently the novel ‘Rebel Falls’ (Three Hills/Cornell University Press):