Jack the Ripper is one of the most infamous murderers of all time. He killed five women in London in 1888 in gruesome fashion. But did Jack the Ripper ever murder people in other countries? Specifically, did he commit a terrible crime in New York City? Aaron Gratton explains.

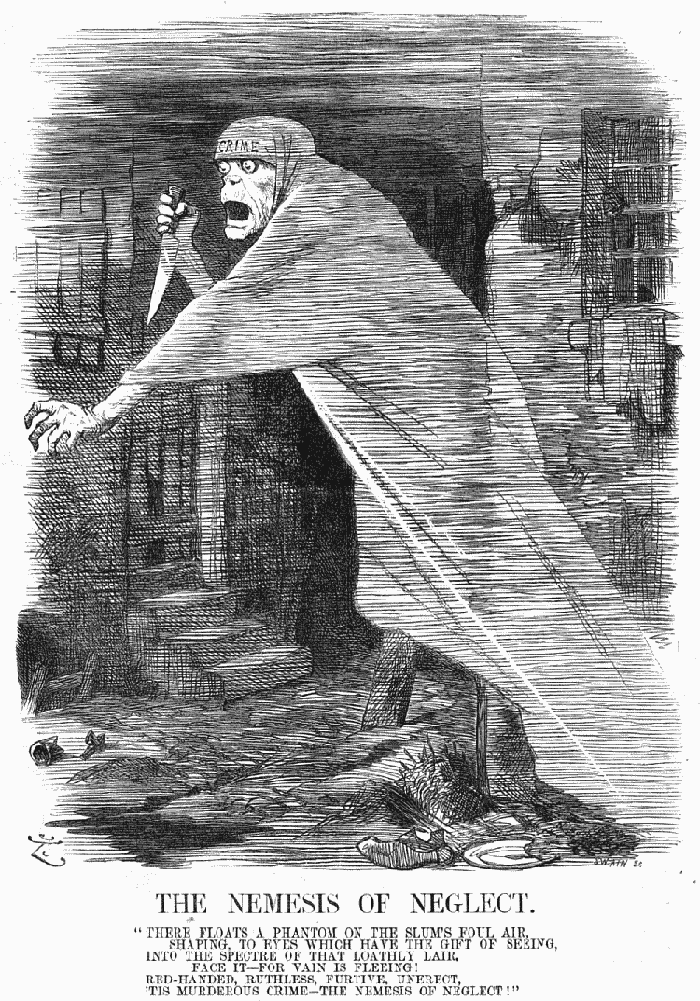

The Nemesis of Neglect, an 1888 Punch magazine cartoon showing Jack the Ripper as a phantom in Whitechapel.

Anyone familiar with British crime history will know the name Jack the Ripper and the Canonical five, but did the killer’s onslaught cross the Atlantic?

In London, England, five women were found brutally murdered in 1888; all bearing similar injuries that suggested a surgical blade was used as the murder weapon. Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly would all be collectively known as the Canonical five, whose lives were brought to a devastating end at the hand of the serial killer simply known as Jack the Ripper.

Many experts believe those five murders, all of which occurred under the mask of the night in Whitechapel, a district in the English capital, to be the killer’s only victims. However, events that transpired three years later in New York question the legitimacy of those claims.

Timeline of Events

· August 31, 1888: Mary Ann Nichols is found dead at 3.40am, she suffered two severe cuts to the throat and the lower part of her abdomen was ripped open by a jagged object

· September 8, 1888: Annie Chapman’s body was discovered at 29 Hanbury Street, also with two cuts to the throat and her abdomen completely cut open – it would later be discovered that her uterus was ripped out

· September 27: The first letter signed from Jack the Ripper, entitled ‘Dear Boss’, is received by the Central News Agency

· September 30, 1888: Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes are killed just an hour apart from each other with the former’s body found in Berner Street and the latter’s in Mitre Square

· October 16, 1888: George Lusk, who headed up the investigation, received the famous ‘From Hell’ letter signed by Jack the Ripper, containing half a kidney that is believed to have belonged to Catherine Eddowes

· November 9, 1888: Mary Kelly, believed to be the killer’s last victim, is found dead in Dorset Street Spitalfields

Other bodies that were originally thought to have been linked to Jack the Ripper were found in the months and years after the five murders, but experts have since ruled out the possibility of the killer having any involvement.

Suspects

Half-an-hour before the discovery of Annie Chapman’s body, a witness claimed to see the woman at 5.30am with a foreign, dark-haired man fractionally taller than the 5 feet tall Chapman. If accurate, the description would match that of Aaron Kosminski, a Polish barber who arrived in London in the early 1880s.

An investigation into the killings claims to have DNA evidence linking Kosminski to the murders, although the time between the events and the investigation have cast serious doubt on the results. In truth, no one will ever be able to definitely name the killer.

The nature of the murders would suggest a killer with a background in surgery, due to the precision of the cuts and removal of various organs and genitalia. On top of this, the letters penned with the name of Jack the Ripper also suggest that the killer, or at least whoever was behind the correspondences, to have poor literary skills owing to misspellings and bad handwriting.

Did The Ripper head to New York?

Almost three years after what was thought to be the killer’s final victim was killed, Carrie Brown was found strangled with clothing and mutilated with a blade in New York on April 24, 1891, sparking rumors that Jack the Ripper had crossed the Atlantic Ocean.

Chief Inspector of New York City, Thomas Byrnes, had boasted on more than one occasion if the killer had ever shown up in his jurisdiction that he would be caught in a matter of days. Three more murders took place in the following 11 days after Brown’s murder, and rumors of a letter from Jack the Ripper sent to Byrnes, taunting the Chief Inspector with a bloodied body part, were rife. This was officially denied, but several police and newspaper sources claimed the rumors to be true.

One last Letter

Nothing else was then heard of the killer for two years since the events in New York City, until October 1893 when a newspaper received a letter believed to be from the killer. The correspondence bore details of the murder of Carrie Brown and, when inspected by a police officer from Scotland Yard, the handwriting of the letter was said to match that as seen in letters received in London in 1888.

If the letter containing details of the murder is indeed from the killer, known as Jack the Ripper, it would be the last known correspondence of the murderer. This is, of course, far from concrete evidence that the same killer that roamed the streets of London in 1888 showed up in New York three years later.

In fact, London’s Metropolitan Police categorically ruled out any involvement of the killer in the death of Carrie Brown in 1891, suggesting this was the work of a copycat that may have been inspired by Jack the Ripper. The theories remain as to the identity of Jack the Ripper, and whether or not the killer did, in fact, turn up in New York, moved on to another city or remained in London without causing suspicion.

Aaron works for the Jack the Ripper Tour in London, UK. You can find out more about the walking tour here.

References

https://whitechapeljack.com/jack-the-ripper-identity-revealed/

https://hubpages.com/politics/Jack-The-Ripper-In-America