The American made “staghound”

tank occupies a place of honor on the campus of the University of Havana. Local

yore says this tank was a Christmas gift from Eisenhower to Batista in 1957.

The armored vehicle is one of the few remaining artifacts of the military

relationship which the Cuban government had with the United States during the

Cold War period.

Unlike

Cuba’s later relationship with the Soviet Union, American security assistance

did not transform Cuba’s capital city into a militaristic enclave. Instead,

during the early period of the Cold War conflict, when the Americans provided

military assistance and arms transfers to the Cuban government, the urban form

and organization of Havana were transformed through the clash of two domestic

forces, the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista and the paramilitary

urban underground opposing his regime.

During

the early Cold War period, Havana’s loyalty to the US was taken for granted and

the government was considered a staunch ally in the fight against communism.

Cuba’s trade relationship with the United States dominated the

country’s economic system so much so that in 1959 almost 80 percent of the

country’s commercial transactions were with the US. The capital city, Havana, was

dominant, handling a majority of the country’s imports, with between 60 and 80

percent of the country’s incoming cargo passing through the port of Old Havana.

Still,

it is important to note that while it may be argued that Cuba was a client of

the United States, the country’s political system was not penetrated in the

strict sense of the term.

In

other words, while more than half of Cuba’s foreign trade was with the United

States, military and aid receipts from the Americans were not more than half

its budget. Actually, in some years, US military assistance was quite

negligible.

Only

after 1972, when Cuba joined the economic arm of the Soviet bloc, COMECON, was

the country penetrated both economically and politically by a Cold War

superpower.

So,

although allied with the US in the 1950s and shaped by the Soviets in the

1960s, it was not until the 1970s — the mid years of the Cold War — that Havana

could be called a Cold War City.

By

then, Fidel Castro’s rise to power and the American response had cemented

a mutual enmity.

By Lisa Reynolds Wolfe. This article originally appeared on www.coldwarstudies.com,

a site about Cold War politics and history that has a particular focus on Cuba.

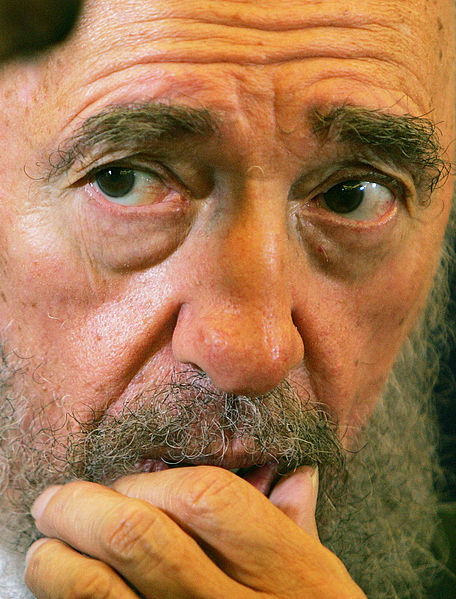

Photograph by Lisa Reynolds Wolfe

This article is the first in a regular series of syndicated articles from some of the most interesting history blogs that will appear on the site.