In 2020 and now 2021, a large number of citizens found themselves homebound. While the stay-at-home orders were a novel experience for most people, the isolation of individuals with a contagious disease has a long history. While it is true that many suffered inconvenience and the disruption of normal routines, the modern home is so well equipped we weren't lacking for much in the way of necessities and comforts. Additionally, those quarantined at home were able to venture outside to replenish supplies or through delivery is needed. It has not always been so easy. The worst outbreak of bubonic plague in early modern England took place in London in 1665. Considering this experience can give us pause to give thanks that we live in the early twenty-first century.

In part 2, Victor Gamma looks at the Great Plague of 1665 in London, how people often lived in cramped conditions in Plague houses, and whether in perspective home quarantine was worth it.

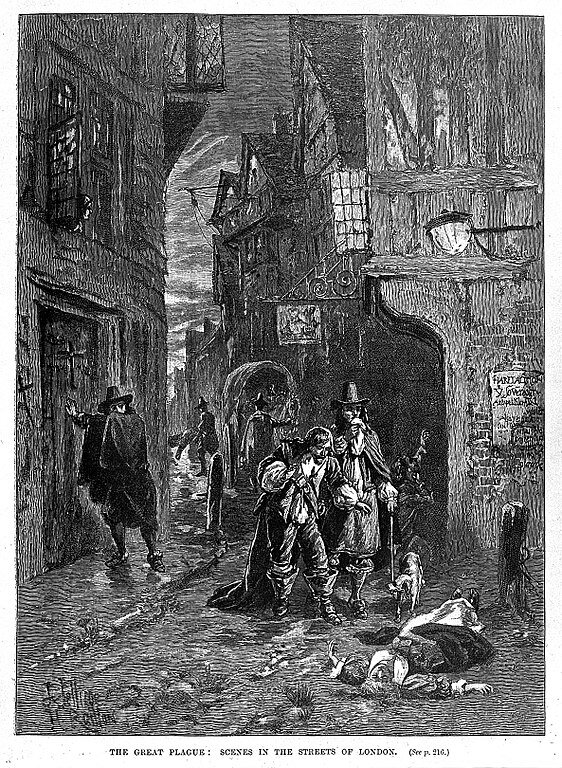

Two men discovering a dead woman in the street during the Great Plague of London, 1665. Wood engraving by J. Jellicoe. Source: Wellcome Trust, available here.

What were conditions like in plague houses? Typical plague homes ranged from modest to ramshackle. Those subject to home quarantine were middle class or poor because those with the means had fled the city before the worst of the outbreak. Middle class Londoners could afford a house on a major street. Under quarantine, the poor suffered greater tribulation because their houses were rather sparsely furnished and lacking in much that might make the quarantine tolerable. The parishes supported those in financial distress in time of quarantine. Households were listed as “chargeable” if they were dependent on the parish for support during the plague. This meant they could not afford the 4 pence that the parish charged per quarantined person per day. In one instance, the records of St. Martin’s show that 84% of individuals in infected houses were “chargeable.” Additionally, the plague increased the number of those financially dependent on parish assistance due to loss of income.

Although the practice of shutting up houses helped stop the spread of disease, the environment inside these plague houses undermined the health of those confined. To compound their suffering, homes at that time had no bathrooms as we know them today. Even the homes of the very wealthy lacked a lavatory. The good health of the inhabitants would normally not last long. After so many weeks of being cooped up, depression and mental lethargy took hold. Fever would often follow, leading to full-on sickness. Although the flight of many doctors earlier in 1665 year made the pitifully weak health system even more ineffective, the Lord Mayor did direct a number of physicians to treat the poor.

Sometimes the supply of food in shut up homes began to dwindle. Lacking preservatives, the food they had left began to rot. Its odor would permeate the air, along with the smell of putrefying water. Conditions were mostly cramped. Unlike the wealthy, the typical quarantined family lacked the space to segregate themselves. The air in that hot, humid summer of 1665, would be stifling in the shuttered, darkened structure. Without light and air, some began losing their grip on reality. In many plague houses one or more people were dead or dying. The mental state of everyone in the home ranged from mild fear to pathological terror. Those still alive knew what awaited them if they became infected: headaches, fever, vomiting, painful swellings on the neck, armpits and groin (buboes), blisters and bruises, coughing up blood and likely death. The atmosphere was rank with the odor emanating from one or more plague-ridden corpses. Even when they had been removed the smell of death and decay would linger. With each fresh outbreak of the epidemic the twenty-day quarantines were extended. Since this was a regular occurrence, the quarantine could go on indefinitely or until the entire household was dead.

Some families held desperate councils and took matters into their own hands. Many an imprisoned person crept up into the second story or attic, waited until the guard was not looking, carefully lowered a rope around the watchman's neck and pulled. They would demand he open the door - or else. If the guard proved stubborn they might keep pulling until he either changed his mind or lost consciousness. Those that lacked the nerve for such drastic measures tried hacking a hole in the back of the house. They were, after all, made only of plaster and narrow strips of wood. Some escaped through the neighbor’s yard using this method. Others threw messages tied to a block of wood or tile to a friend in the street, pleading with them to drug the guard. Those that lacked the wherewithal for any of these actions were often condemned to watch as their loved ones died, one by one.

Pushback

Protests against the practice did occur. The level of distress of those home-quarantined is indicated by the number of violations recorded in court sessions. Offenses included illegally allowing inhabitants to leave their house or continuing to carry on business despite being quarantined. The government narrative held that its pandemic-control measures were necessary for the safety of the entire community. Parallel to this ran a largely popular counter-narrative that saw the home quarantines as a heartless punishment forced upon the poor that did little to stop the disease from spreading. For one thing, government policies strictly forbade the visiting of the sick by anyone other than plague officials. This severely disrupted the normal ties and customs of kinship and charity. Poet George Wither wrote of this:

That man was banished from the public sight Imprisoned in his house both day and night. As one that meant the Citie to betray And (to compel that his unwelcome guest Should keep within) his dore was crost and blest And for that purpose, at the door did stand An armed watchman, strengthened by command.

Partly to blame was the flight of the well-to-do, which took place that spring. The unintended consequence was that the overwhelming majority of victims were the poor and middle class, making it appear that government disease-control policies were aimed at the lower classes. An anonymous pamphlet called Plague Houses blasted the practice of home quarantine as "this dismal likeness of Hell, contrived by the College of Physicians." Even some doctors condemned the practice. It was, declared one physician, "Abhorrent to Religion and Humanity even in the Opinion of a Mohometan." Many argued that science simply did not back up the practice. One physician noted that "the tedious confinement of sick and well together" merely made the healthy "an easier prey to the devouring Enemy." Some sensible souls dared suggest that it would be more effective to separate the healthy from the infected. These voices of reason were drowned out by a chorus of fear. In 1604 Thomas Dekker wrote “Whole households and whole streets are strickent/the sick do die, the sound do sicken.”

A return to normality

The unpopular orders sometimes led to violence. For example, in 1637 a shoemaker named John Clarke refused to obey an order toleave his house and go to a “pestfield.” The justice of the peace sent bearers (those who carried corpses to burial) and other plague workers to his house in order to tell Clarke and his household to vacate their home. They had orders to force the family out if they persisted in their noncompliance. Riots even took place against shutting up the sick. In April 1665, as the shutting up of infected houses was just beginning, a report was given to the authorities of a case alarming enough to warrant a hearing and discussion in the presence of King Charles II. The report stated that infected houses at St. Giles were subject to a “ryot” in which the Cross and paper affixed to the door were taken off. The door was opened “in a riotous manner.” The inhabitants were let and “permitted to goe abroad into the street promiscuously.” The Lord Chief Justice was ordered to investigate and prosecute the offenders severely for committing a crime “of soe dangerous a consequence.” The “ryot” proved to be an exception, though, for as the plague spread, fear of infection accomplished what the authorities could not and most people avoided the sick. Nonetheless, such incidents reinforced the popular perception of home quarantine as a punitive measure.

Fortunately, after the fading of summer’s heat, the crisis subsided. With the cooler weather of autumn the first ray of hope appeared. The Mortality Bills for September registered the first significant decline in fatalities. With some fluctuation the decline continued into the winter. By October the diarist Pepys could write; “... there are great hopes of a great decrease this week; God send it!” Pepys’ optimism was soon realized. By the end of November London began its painful return to normal conditions.

Quarantine in perspective

Was the home-quarantine worth the cost? The consensus is that the home quarantines may have helped to stop the spread of plague to an extent. According to Daniel Defoe in his Journal of the Plague Year, wherever the practice was instituted “it was with good success; for in several streets where the plague visited broke out, upon strict guarding the houses that were infected, and taking care to bury those that died immediately after they were known to be dead, the plague ceased in those streets.” Although Defoe based his Journal on the recollections of survivors, many contemporaries disagreed, blaming the high mortality rate and personal suffering on the practice of home quarantine. One problem was the social nature of households. As mentioned already, the members of a quarantined home of middle or poor social class lacked the space to avoid congregating together throughout the day. This insured the spread of infection. The strict approach of the government also unwittingly spread infections. One order made it illegal to so much as sit at the door of a quarantined house. The punishment was that they “be shutt up with ye rest of ye infected persons.” In this way, many healthy individuals fell victim to the plague.

Conversely, under the restrictions, ordinary life and commerce suffered devastating effects. Almost any street one walked down was eerily silent. Trade declined so dramatically that thievery and begging ran rampant. On average one to three people died in infected homes. All too often entire households perished, rising to a peak in the summer. By the time the plague had run its course as many as 100,000 had died in London, representing at least 15% of the population.

The current Covid-19 stay at home orders have been credited with helping stop the spread of the virus. As in 1665, it has triggered a recession and caused considerable suffering for those who lost jobs or endured financial loss. Despite this, most home-quarantined people in 2020 did not complain of anything approaching the hellish experience of 1665. However restrictive we have found our current on-going quarantine, a look back at times past can be a cause to give thanks.

Now, if you want to learn about Tudor England, you can read Victor’s series on Henry VIII’s divorce of Catherine of Aragon here.

References

Anonymous The Shutting Up of Infected Houses (pamphlet), 1665.

Antiquarian Repertory. London, Printed and published for E. Jeffery, 1807-09.

Defoe, Daniel Journal of the Plague Year, first published March, 1722.

Gregory, Charles William, Public Opinion and Records, Published: The Author, 1856. Digitized: July 4, 2006.

Leaser, James, Plague and Fire. New York: McGraw Hill, 1961.

The National Archives Education Service: The Great Plague 1665 -1666 How did London respond to it? (Educational Material)

Newman, Kira L. S. Dolby. “Shutt Up: Bubonic Plague and Quarantine in Early Modern England.” Journal of Social History Vol. 45, No.3. (Spring 2012), pp. 809-834.

Pepys, Samuel, Diary.

Certaine necessary directions, as well for the cure of the plague, as for preventing the infection: with many easie medicines of small charge, very profitable to his Majesties subjects. London: Robert Barder and John Bill (By the Royal College of Physicians, London, 1636.