The British Empire did not suddenly start its decline in the post World War Two period; instead it was an event that began much earlier. The British Empire had been expanding and stretching out across the globe since the 1600s. After the American War of Independence Britain began to build a new empire with a new urgency. The British Empire grew to some thirteen million square miles and to govern over five hundred million subjects. This article focuses on Britain’s decline after World War 1 by looking at Egypt, Iraq, Ireland, and India.

Steve Prout explains.

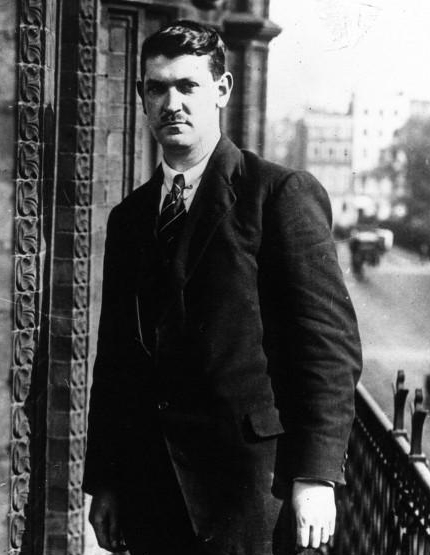

King Faisal I of Iraq. He was King from 1921 to 1933.

The Decline of the British Empire

The contraction of the British Empire had already begun in the nineteenth century starting with Canada. Up until to 1921 Britain’s presence in the world was occupying a quarter of the planet’s land surface. Certain countries at distinct stages within that empire enjoyed a more independent status than others. Australia and New Zealand achieved their independence peacefully but others like Ireland would be forced to take a more violent approach in fighting Imperialist domination.

Independence was driven by motives such as the general desire of those nations to run their own affairs and the need to detach themselves from colonial repression and bloodshed (such as in Ireland and India). There was also the inequalities of trade in India, Iraq was piqued that they had found themselves rid of Ottoman only to have lost that freedom to British rule and subsequently lose control of their natural resources, and then just as important colonial rule often involved being dragged into the conflicts of far off European nations.

The Dominions

Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand independence came in the form of Dominion status which was achieved by a more diplomatic avenue. Dominion status was defined as ”autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.”

Britain granted a Dominion Status in the 1907 Imperial Conference to a select number of nations. Australia and New Zealand were enjoying this privileged status since 1900 and 1901 respectively. South Africa would follow in 1910 after a series of unifications within its borders. Canada had already enjoyed this status since 1867. The Irish Free State would follow in 1922.

In 1926 the Imperial Conference revisited Dominion status with the Balfour Declaration which would be formalised and recognised in law with the Statute of Westminster in 1931. The British Empire now was now known as the Commonwealth of Nations. The Imperial hold had loosened but Britain initiated the change to allow complete sovereignty for the Dominions. The First World War left Britain with enormous debts, and reduced her ability and in turn her effectiveness to provide for the defence of its empire. The larger Dominions were reluctant to leave the protection of Britain as many Canadians felt that being part of the British Empire was the only thing that had prevented them from the control of the United States, while the Australians would later look to Britain for defence in the face of Japanese militarism. Except for the Irish Free State this change did not stop these dominions from supporting Britain in her declaration of war against Germany in 1939.

But between the interwar years there were further challenges to Britain’s Empire from various parts of the world. By the time the Great War was over India, Egypt, Ireland, and Iraq were all taking a less than passive approach in their demand for independence.

Egypt

Britain had partially governed Egypt since the 1880s under a veiled protectorate primarily to look after her interests and investments. It was never officially part of the British Empire in the same way for example as Rhodesia, Malaysia, India, or Cyprus. As soon as the Great War ended Egypt was demanding her own independence. By 1919 a series of protests had morphed into uprisings against British rule known as the 1919 Revolution. In that same year at the Paris Peace Conference, Egypt had sent representatives to seek independence from Britain. The sheer volume of international issues following the war distracted the allies and put Britain’s particular attentions elsewhere and Egypt left empty handed.

In 1920 an Egyptian mission led by Adli Pasha was invited by Britain to address the issues in Egypt. This mission arrived in the summer of that year and presented a set of proposals on independence for both Britain and Egypt to agree but after a return visit in June 1921 to ratify the agreement the mission left in “disgust”. No agreement could be reached on these proposals by Parliament or the Dominions at the Imperial Conference, notably over the control of the Suez Canal. More unrest in Egypt would follow resulting in martial law and by December 1921 the British realized that the situation was clearly unsustainable, and so they declared the Unilateral Independence of Egypt in February 1922. This independence would be in a limited form as the British still had control of the railways, police, courts, army, and the Suez Canal. By 1936 British rule had unwound further as King Farouk agreed an Anglo- Egyptian Treaty leaving just a garrison of troops to guard Britain’s commercial interests in the Suez Canal. This unwelcome presence was enough to involve Egyptian territory in the Second World War to the chagrin of the Egyptians.

Iraq

In 1932 Britain granted Iraq independence after a brief post war mandate that presided over the newly formed nation after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. From as early as 1920 Iraq had revolted against British occupation. Iraq now broke free of Ottoman rule only to find it had been substituted by their new British masters. The British military quickly quashed the revolts but like Ireland and other areas of the empire military repression was not the lasting solution, and the British continued in vain in Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra.

Part of the answer was giving the throne to a British friendly monarch King Fayṣal, with British control in the background. A plebiscite in August 1921 augmented his position. A treaty of Alliance replaced the formal mandate obligating Britain to provide advice on foreign and domestic affairs, such as military, judicial, and financial matters - but the matter was not yet over.

King Faisal would still depend on British support to maintain his rule. The Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 provided for a close alliance which essentially meant Iraq had limited control on matters of foreign policy and would have to provide for an ongoing British military presence on her territory. The conditions granted the British the use of air bases near Basra and at Habbaniyah and the right to move troops across the country for a twenty-five-year duration. Despite being a sovereign state by 1932 this treaty would find Iraq being involved in World War Two as the British fought against Nazi infiltration.

Ireland

Ireland, like India and Iraq, was another violent struggle for independence, and this was closer to home shores. The conflict would inflict wounds that both sides would not easily forget and forgive at least well into the twenty-first century.

The desire for home rule was long anticipated and had been on the negotiating table since the nineteen century premiership of William Gladstone. All efforts to push the Home Rule Bill of 1886 had been thwarted by the political opposition because it was feared an Independent Ireland would pose a security threat providing an opportunity for Britain’s foes. Also, for the diehard Imperialists this might prompt other demands for independence across the Empire.

The patience of the Irish nation would grow thin. A third Home Rule Bill was almost formalised in 1914 but the outbreak of war suspended its implementation. The ever long wait and the lack of clarity over the fate of Northern Ireland’s Six Counties caused an escalation in violence. The most notable event was the Easter Rising in 1916 but more violence and further escalations occurred in the post war years as the British tried to reassert control with military means. It was by then too late for such measures.

Ireland would make unsuccessful attempts to gain support at the 1919 Peace Conference in Paris and in particular President Wilson. In 1920 the Government of Ireland Act (fourth Home Rule Bill) was introduced by the British Government. It was far from satisfactory as far as Ireland was concerned as they wanted to completely break away from its relationship with Westminster and its unpopular allegiance to the Crown. It also divided off the Northern Ireland from the rest of the country which remained part of the United Kingdom.

In 1922 dominion status was granted but it was not enough for the independence movement. The newly Irish Free State wanted total severance from the crown and the removal of the oath of allegiance. Dominion status was not satisfactory in the immediate post war years, and the Irish made strenuous representations to the League of Nations that they had the capability to become a fully independent nation, which they would achieve by 1937.

A number of laws that were passed, including the Constitution (Amendment No. 27) Act 1936 and the Executive Powers (Consequential Provisions) Act 1937, removed the Imperial Role of Governor General. Then, using religious grounds following the outrage from King Edward’s abdication, Ireland finally severed all remaining ties with Britain to become a fully independent nation. The Irish experience and the way they achieved their independence constitutionally would be noticed and emulated by other colonies much later.

India

India was also challenging British rule in this interwar period. The Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms of 1917 that became the 1919 Government of India Act was an early attempt to establish a self-governing model for India. Indian nationalists felt that it fell short of expectations after their commitment to Britain in the First World War. The post war period had been hard on India, the flu epidemic and Imperialist free trade had affected society in all kinds of ways. The Rowlatt Act also fuelled the nationalist anger and allowed for the detention of any protesters and suppression of unrest. Protests encountered a typical coercive and violent reaction by Britain. This use of force was particularly heavy handed in Amritsar in April 1919 when Brigadier General Dyer had his troops open fire on a crowd killing almost four hundred local protestors. It was sufficiently bloodthirsty to cause even the bellicose Churchill to deem it “utterly monstrous,” but a subsequent enquiry failed to deliver justice to the perpetrators and exacerbated the situation. The British response was all in vain and in fact it fuelled Gandhi’s Non-Co-operation campaign. The issue would not go away but it would take another twenty-seven years to achieve independence.

Conclusion

The decline of the Britain’s Empire only accelerated in the post war period. The “Wind of Change” that Harold Macmillan spoke of on his visit to Africa in the 1950s was the just a continuation of the Empire’s sunset from many decades earlier. By the 1970s little of the Empire remained save for a few scattered islands around the world.

What do you think of the decline of Britain’s Empire after World War One? Let us know below.

Now read about Britain’s 1920s Communist Scare here.

References

Britain Alone – David Kynaston – Faber 2021

AJP Taylor – English History 1914-1945 – Oxford University Press 1975

The Decline and Fall of The British Empire – Piers Brendon – Vintage Digital 2010

Nicholas White – The British Experience Since 1945 – Routledge 2014

Losing Ireland, losing the Empire: Dominion status and the Irish Constitutions of 1922 and 1937 - Luke McDonagh

International Journal of Constitutional Law, Volume 17, Issue 4, October 2019, Pages 1192–1212