Millions of tourists visit London each year to take in the city's iconic architectural sites and attractions. It is hard to imagine that the iconic River Thames was once a site of unbearable stench and disease that choked Londoners. The summer of 1858 was labelled as the Great Stink by the British press and was a result of many years of poor living conditions, sanitation and a lack of public health reforms. The Great Stink was the tipping point that encouraged a change of attitude towards public health from a laissez-faire attitude, where the government did not interfere with public health, to a desire to improve living conditions. A laissez-faire attitude meant that government officials took a step back from interfering with social welfare and let issues take their own shape naturally.

Amy Chandler explains.

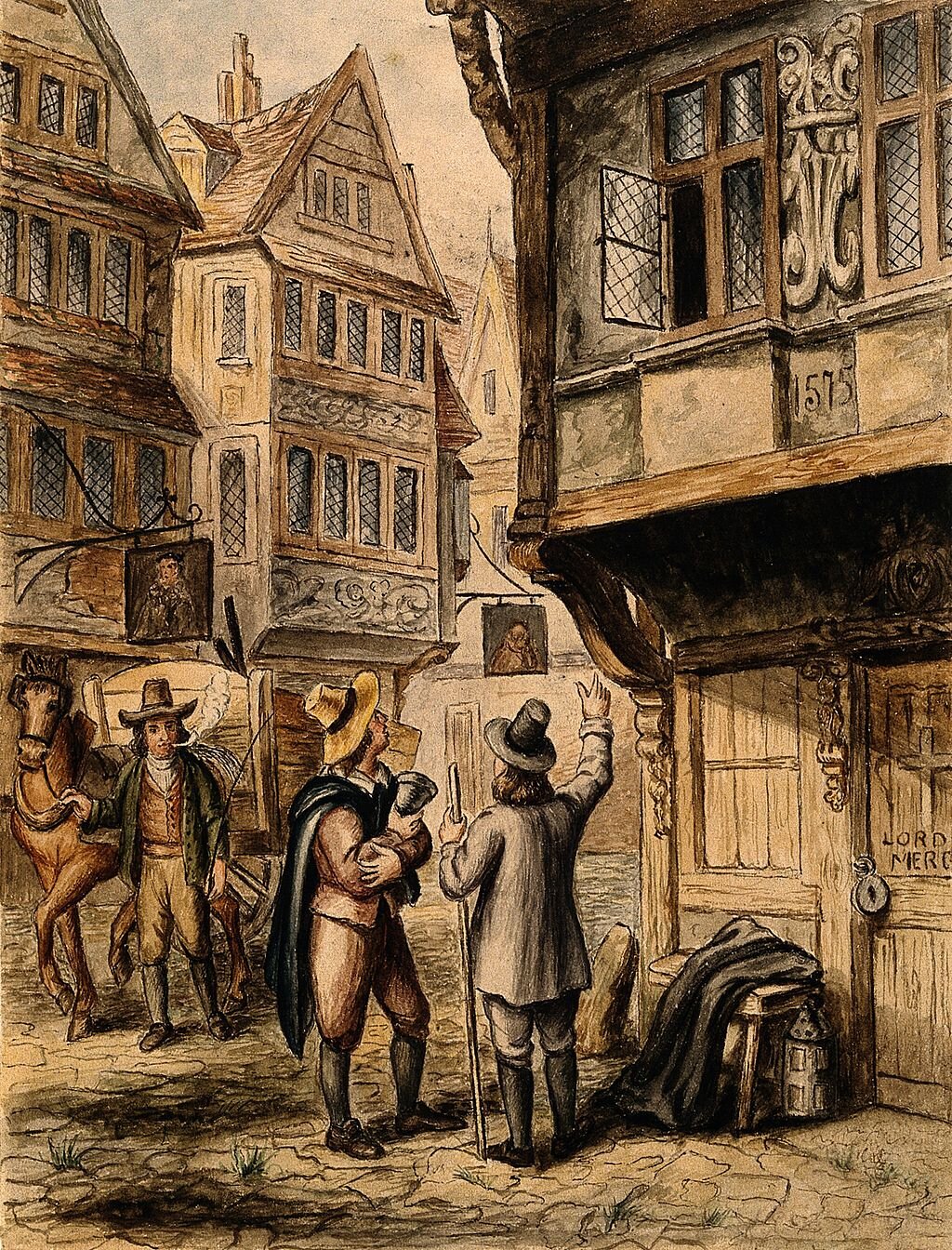

A dirty Father Thames in 1n 1848 edition of Punch magazine.

This article will explore public health during 1842 to 1865 by focusing on the work of Dr John Snow and the cholera outbreaks, Sir Edwin Chadwick's contribution to the Public Health Act, and Joseph Bazalgette's construction of the London sewer system. Part one will explore the factors that contributed to the Great Stink, such as overcrowding, the introduction of flushing toilets, cholera outbreaks and a call for public health reforms. Part two will analyse how Parliament handled the situation of the noxious smells from the River Thames through Bazalgette’s construction of the sewer systems.

Investigations by Sir Edwin Chadwick 1842-1848

In 1842, social reformer Edwin Chadwick published a report for the Poor Law Commissioner entitled Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Poor. This report provided statistical evidence that outlined the stark contrast in life expectancy determined by class and residency. Chadwick highlighted how life expectancy in large cities, like London, was dramatically lower than in rural areas.(1) Laborer occupations were the most at risk of early death compared to professional trades.(2) Chadwick’s report is now seen as a “monumental step toward accepting and dealing with social costs of economic progress”, but not at the time of publication.(3) However, in 1842 Chadwick discovered that disease and infection spread throughout all classes of society. The poor suffered the most because of their unsanitary living conditions. Chadwick’s finding caused unrest with politicians. His report opposed the popular view that an individual was poor because it was their fault. This attitude meant that change was slow throughout the nineteenth century.

Furthermore, Chadwick’s report highlighted that social welfare concerns could only be resolved through financial improvements and changes approved by government. Chadwick suggested that the financial implications for tenants and owners to ensure good drainage and clean water supply to their inhabitants would be “offset by the reduced cost of tending to the ill” in the future.(4) Other measures included improved drainage, removal of refuse from houses, streets and roads and placed in “moveable vessels”.(5) The idea here was to spend money to improve the living conditions to save money in the future, as the population would be healthier and less likely to need medical assistance. Chadwick suggested taxing households to contribute to the cleaning programmes but he misunderstood that many people struggled to afford necessities in everyday life.

Chadwick’s theory does have some credibility that by improving the living conditions in densely populated areas would reduce the spread of disease. At this point in history, the theory of miasmas was still widely believed and accepted as diseases caused by bad smells rather than bacteria and viruses. Despite medical and scientific beliefs as largely inaccurate to what caused disease, the measures that Chadwick was describing were credible ideas. For example, providing clean water supplies reduced the risk of contracting an illness, and removing rotten household food and other waste from the streets, housing and roads deterred the presence of rats and mice infiltrating densely populated areas.

Chadwick encountered much opposition from Parliament as the poor working-class created the wealth that many of the upper class experienced the benefits from exploited labor. Change in attitudes towards creating the first Public Health Act was not until 1848 after London suffered another deadly cholera outbreak, although this act did not require local medical officers to enforce or design cleaning programs to improve sanitation conditions.(6) Parliament passed the 1846 and 1848 Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act, including “filthy and unwholesome” buildings and houses, “foul and offensive ditch, gutter, privy, cesspool or ash pit”, and removal of refuse and waste.(7) This act closed old cesspits, which caused all new waste to flow into the River Thames, with open cesspits unable to handle the growth in population and new flushing toilets leaked sewage into water supplies into the river.

The 1848 Public Health Act enforced appropriate drainage and sewer systems that distributed waste into the River Thames. Many believed that sewage in the river would magically disappear. In reality, waste stagnated within the water, and Londoners continued to use this water to wash and drink. Many did not understand that the River Thames is a tidal river, where water levels are influenced by the tide, resulting in circulating waste.(8) In 1851 The Great Exhibition in London, showcased the newest and high-tech inventions on an international stage that illustrated Britain’s power and wealth.(9) One invention that proved popular was the flushing toilet and it was made available to the public after 1851. Like many of the inventions displayed at The Great Exhibition, the flushing toilet was only affordable by the wealthy upper classes. Many toilets flushed into old cesspits that were incapable of containing the amount of waste pumping through, causing overflowing waste into the Thames and drinking water.(10) Despite technological advances of the flushing toilet, London did not have a sewer system capable of handling this new technology.

The cholera epidemic and Dr John Snow’s breakthrough

Another cholera outbreak, in 1854, erupted throughout London and raised concern around the living conditions in London’s most densely populated areas. Dr John Snow investigated the cause of the disease by analysing the water supplied from the River Thames and water supplied by wells and natural springs. London suffered three major cholera outbreaks, but in 1854 the outbreak was different in the poverty-stricken area of Broad Street, Soho near Golden Square. Snow decided to investigate the deaths from cholera by using a grid system and map of the local area to plot the radius of infections by contacting the residents and workers in the local area. Snow’s findings revealed that those who drank from the Broad Street pump, which filtered water directly from the River Thames, became severely ill with cholera. Snow documented his investigation noting, “all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the pump” and suspected “some contamination of the water of the much-frequented pump in Broad Street”.(11) Snow examined the water from Broad Street and compared water samples from the river and wells. The results emphasized that water from the Thames had physical specks floating in the water that supported Snow’s thinking.(12)

Snow concluded that the water from the River Thames was contaminated and caused cholera outbreaks. In light of this discovery, Snow ordered officials to stop public use of the Broad Street pump. In doing so, Snow discovered that infection and mortality rates reduced rapidly and proved his theory. In October 1854, Snow investigated the water quality supplied by companies in Southwark and Vauxhall that pumped drinking water from the Thames and compared this to water provided by Lambeth water company, who pumped their water from a less polluted area in the Thames; Lambeth had a lower mortality rate in comparison to the Southwark and Vauxhall areas.(13) Of course, Snow’s understanding of science and disease was founded on the miasma theory, but his investigations disproved the miasma theory but he was unsure why or how as Germ theory was not discovered until 1861. Despite Snow’s investigation, many politicians were still adamant in their belief of bad smells as the cause of disease, and this attitude halted progress in improving public health.

Solved one problem to cause another

The work of Snow and Chadwick progressed attitudes towards public health and improved living conditions for Londoners. But they could only do so much as many government officials were resistant to believing anything other than bad smells causing disease. The Public Health Act aimed to improve life in poverty-stricken areas but in reality, created overfilled cesspools that contaminated water supplies, turning London's iconic river into a vat of stench and disease. All these factors became culminated into the 1858 Great Stink and became a turning point in changing government policies towards public health and sanitation by constructing a sewer system that is still in use today.

Part two will explore how the Great stink forced government officials to tackle London’s sewage and waste problem by commissioning Joseph Bazalgette to flush the River Thames and clean up London’s act.

Now read party 2 on the Great Stench and its aftermath here.

1. The National Archives, Victorian Britain, The National Archives: Find Out More, undated <https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/victorianbritain/healthy/fom1.htm> [accessed 4 March 2022].

2. Ibid.

3. I. Morley, ‘City chaos, contagion, Chadwick, and social justice’, Yale J Biol Med, vol. 80, (2007),p.61.

4. M. Williams, ‘Kingsley, Millar, Chadwick on Poverty and Epidemics’, 26 May 2020, The Victorian Web < https://victorianweb.org/science/health/williams1.html > [accessed 4 March 2022].

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. UK Parliament, ’Nuisances’, 2022, Uk Parliament <https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/about-the-group/nuisances/nuisances/ > [accessed 4 March 2022].

8. D.G, Hewitt, ’18 facts about the 1858 Great Stink of London’, History Collection, 3 June 2019 < https://historycollection.com/18-facts-about-the-1858-great-stink-of-london/ >[accessed 4 March 2022].

9. L. Picard, ‘The Great Exhibition’, The British Library, 14 Oct 2009 <https://www.bl.uk/victorian-britain/articles/the-great-exhibition> [accessed 4 March 2022].

10. Hewitt, op.cit.

11. T.H. Tulchinsky, ‘John Snow, Cholera, the Broad Street Pump; Waterborne Diseases Then and Now’, Case Studies in Public Health, (2018), p.81.

12. K, Tuthill, ‘John Snow and the Broad Street Pump’, UCLA, 2003 <https://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/snowcricketarticle.html >[accessed 8 March 2022].

13. Tulchinsky,op.cit,p.82.

Bibliography

Authority., ‘Cholera epidemics in Victorian London’, The Gazette, 2016 <https://www.thegazette.co.uk/all-notices/content/100519 >.

BAUS.,‘A Brief History of The Flush Toilet: From Neolithic to modern times’, The British Association of Urological Surgeons, undated <https://www.baus.org.uk/museum/164/a_brief_history_of_the_flush_toilet >.

Bibby, M., ‘London’s Great Stink’, Historic UK, 2022 <https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Londons-Great-Stink/ >.

Hewitt, D.G.,’18 facts about the 1858 Great Stink of London’, History Collection, 3 June 2019 < https://historycollection.com/18-facts-about-the-1858-great-stink-of-london/ >.

LSHTM., ‘Sir Edwin Chadwick 1800 – 1890’, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2022 < https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/aboutus/introducing/history/frieze/sir-edwin-chadwick >.

Morley, I., ‘City chaos, contagion, Chadwick, and social justice’, Yale J Biol Med, vol. 80, no. 2, June, 2007,pp. 61-72.

Picard, L., ‘The Great Exhibition’, The British Library, 14 Oct 2009 <https://www.bl.uk/victorian-britain/articles/the-great-exhibition>.

Porter, D.H., ‘From Inconvenience to Pollution -- Redefining Sewage in The Victorian Age’, The Victorian Web, 1999 <https://victorianweb.org/technology/porter9.html >.

The National Archives, Victorian Britain, The National Archives: Find Out More, undated <https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/victorianbritain/healthy/fom1.htm>.

Tulchinsky, T.H., ‘John Snow, Cholera, the Broad Street Pump; Waterborne Diseases Then and Now’, Case Studies in Public Health, 2018, pp. 77-99.

Tuthill, K., ‘John Snow and the Broad Street Pump’, UCLA, 2003 <https://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/snowcricketarticle.html >.

Uk Parliament, ’Nuisances’, 2022, Uk Parliament <https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/about-the-group/nuisances/nuisances/ >.

Williams, M., ‘Kingsley, Millar, Chadwick on Poverty and Epidemics’, 26 May 2020, The Victorian Web < https://victorianweb.org/science/health/williams1.html >.