The ancient Olympic games were originally a one-day event and the first recorded event was in 776 BCE; however, in 684 BCE, the games were extended to three days, then later to five days. The games were held every four years and are among the most celebrated traditions of ancient Greece.

Terry Bailey explains.

A depiction of the ivory and gold statue of Zeus.

The ancient Olympic games were not merely athletic contests but a festival that honored the Greek god Zeus, (Ζεύς). Through their duration and influence, the Olympics became a cornerstone of Greek culture, fostering unity, showcasing physical prowess, and celebration. In Greek mythology, it is said that Heracles, (Ἡρακλῆς), (Latin, Hercules), the son of Zeus and the mortal woman Alcmene was the founder of the Olympic games.

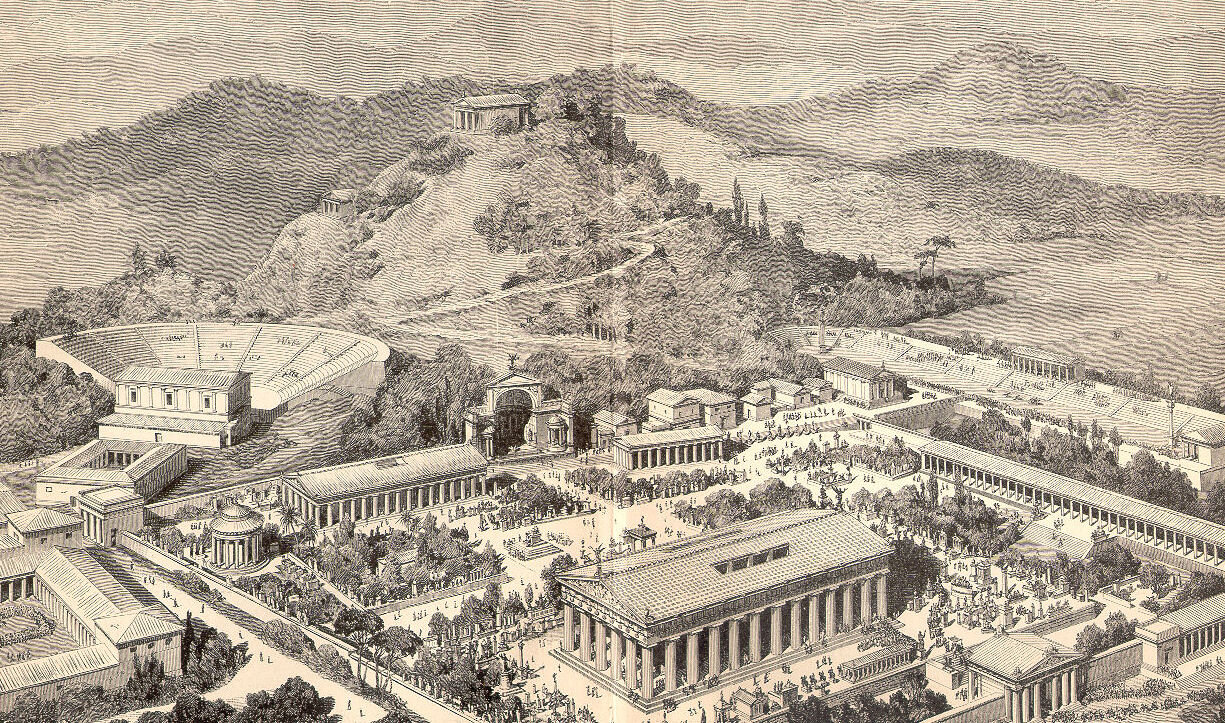

The ancient Olympics were held in Olympia, (Ὀλυμπία), a sanctuary site in western Peloponnese, a site that honored Zeus, who was the god of the sky and thunder and who ruled as king of the gods on Mount Olympus, (Όλυμπος). The sanctuary housed the magnificent ivory and gold statue of Zeus, designed and created by the sculptor Phidias, (Φειδίας), 480 – 430 BCE. The statue of Zeus was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and served as the central location for these games. The games' religious significance was profound, with numerous rituals and sacrifices performed to seek Zeus's favor and blessing.

Events

The Olympic Games began as a single race, the stade race, (Stadion), a sprint covering roughly 192 meters, (in today's unit of measurement), over time the games expanded to include a variety of events:

Stadion: The original footrace, covering one length of the stadium, approximately 192 meters and the precursor to the modern 200-metre race

Diaulos: A double stade race, twice that of the stadion and the precursor to the modern 400-metre race

Dolichos: A long-distance race, varying from 7 to 24 stades.

Hoplite Race: A race in armor, simulating military readiness.

Pentathlon: A five-event competition including a discus throw, javelin throw, long jump, stadion, and wrestling.

Side note: Athletes when jumping utilized a stone as a weight called halteres to increase the distance of a jump. They held onto the weights until the end of their flight and then jettisoned it backwards. Whereas, the discus was originally made of stone then later it was made of bronze. The technique was very similar to today's freestyle discus throw.

Wrestling (Pale): A grappling event where the objective was to throw the opponent to the ground. This was highly valued as a form of military exercise without weapons. It ended only when one of the contestants admitted defeat.

Boxing (Pyx): Boxers wrapped straps (himantes) around their hands to strengthen their wrists and steady their fingers. Initially, these straps were soft but as time progressed, boxers started using hard leather straps, often causing disfigurement of their opponent's face. Later the Romans adopted boxing into their gladiatorial games, however, in the Roman version the leather straps often had metal studs attached.

Pankration: A no-holds-barred contest combining wrestling and boxing. This was a primitive form of martial arts combining wrestling and boxing and was considered to be one of the toughest sports. Greeks believed that it was founded by Theseus when he defeated the fierce Minotaur in the labyrinth.

Equestrian Events: Including chariot racing and horse racing, held in the hippodromos, (ἱππόδρομος), Latinized to hippodrome from hippos, (ἵππος, horse) and dromos, (δρόμος, road/course), hence race course, race track.

These events tested the athletes' strength, speed, endurance, and skill, reflecting the Greek ideal of athletic excellence. Winning an event at the Olympics brought immense honor and fame, however, it should be noted, unlike the modern games each event had only one victor with no silver or bronze-placed athletes.

Victors, known as Olympionikes, received a wreath made of wild olive leaves, known as a kotinos, from the sacred olive tree near Zeus's temple. Beyond this symbolic prize, winners were often celebrated as heroes in their hometowns and received numerous amphorae of olive oil a very valuable commodity at the time.

Additionally, their hometown often honored the winners with other substantial material rewards, such as money, meals at public expense, or even the erection of a statue in their honor. Poets like Pindar would compose odes celebrating their victories, ensuring their names were immortalized.

Major athletic festivals

However, the Olympics were just part of the larger cycle of Panhellenic Games, which included three other major athletic festivals:

· The Pythian Games were established in 582 BCE and held in Delphi in honor of Apollo, the god of music, arts, and prophecy. These games included musical and artistic competitions alongside athletic events. Victors received a laurel wreath, symbolizing Apollo's sacred tree.

· The Nemean Games were established at the sanctuary of Zeus in Nemea in 573 BCE, and dedicated to Zeus. These Games were held every other year, (2nd and 4th year), in the same years that the Isthmian Games are held and were similar to the Olympics, these games included various athletic contests. Winners were crowned with a wreath of wild celery.

· Isthmian Games, were established near Corinth in 582 BCE the same year as the Pythian Games began in Delphi. They were also held every 2nd and 4th year, like the Nemean Games, but in the spring. These games were held in honor of Poseidon, (Ποσειδῶν), who presided over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses, and featured athletic and musical competitions, with victors receiving a wreath of pine leaves, later replaced by a wreath of dried celery.

Each of these games shared the common goal of celebrating athletic excellence and honoring the gods, but they also played a crucial role in fostering unity among the often-fragmented Greek city-states.

Conclusion

The ancient Olympic Games continued for nearly 12 centuries until they were suppressed in the late 4th century CE by Emperor Theodosius I, who sought to impose Christianity and suppress pagan traditions. Despite their cessation, the spirit of the ancient Olympics lived on, inspiring the modern Olympic movement that began in 1896.

In conclusion, the ancient Olympic Games were a remarkable fusion of sports, religion, and culture. The games honored Zeus and celebrated human excellence, leaving an indelible mark on history. Alongside other Panhellenic festivals, they exemplified the Greek commitment to both physical prowess and divine reverence, creating a legacy that endures to this day.

Find that piece of interest? If so, join us for free by clicking here.

Point of interest

The 26.2-mile marathon of today's Olympics can trace its origins back to ancient times, in addition to, the 1908 Olympics.

The modern marathon's distance of 26.2 miles (42.195 kilometers) has its origins in both ancient and modern history. The marathon race commemorates the legendary run of Pheidippides, an ancient Greek messenger who, according to legend ran across the mountain track in full armor from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens in 490 BCE to announce the Greek victory over the Persians. Upon delivering his message, νικῶμεν (nikomen, (We win)), Pheidippides is said to have collapsed and died. It is from the Greek word for (win/victory), that the famous running shoe brand found its name, (Nike).

Originally, the marathon distance was approximately 24.85 miles (40 kilometers), reflecting the distance from Marathon to Athens. However, the distance was standardized at 26.2 miles during the 1908 London Olympics. This change occurred because the course was extended to allow the race to start at Windsor Castle and finish in front of the Royal Box at the Olympic Stadium, making the distance exactly 26 miles and 385 yards, (26.2 miles).

Therefore, the marathon race is named after the Battle of Marathon, a crucial conflict in ancient Greek history. Characters like Pheidippides became symbolic of endurance and heroism, embodying the spirit of the event, which has since evolved into a cornerstone of modern athletic competition.