The US Supreme Court becomes a very important political issue whenever a vacancy arises. Here, Jonathan Hennika continues his look at the history of the US Supreme Court (following his article on Marbury v Madison here), and focuses on slavery. He looks at the case of Dred Scott, and the 1850s ruling that said freed slaves were not US citizens.

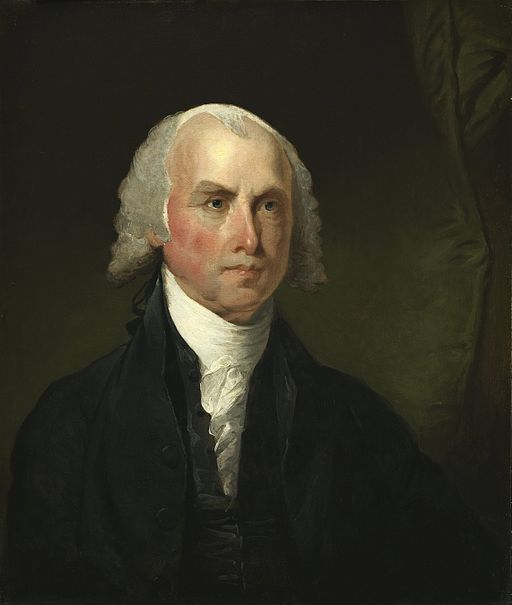

Dred Scott, circa 1857.

In his Congressional testimony refuting the allegations of Dr. Christine Ford, Judge Brett Kavanaugh said in part: “This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit, fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election, fear that has been unfairly stoked about my judicial record, revenge on behalf of the Clintons and millions of dollars in money from outside left-wing opposition groups.”[i]In 2018 the political reality is the line drawn between the Right (Conservatives/Republicans) and the Left (Liberals/Democrats). As the final arbiter of all things Constitutional, Supreme Court nominees have and always will be a political firestorm. After his testimony, concerns were raised by the American Bar Association, the American Civil Liberties Union, and other organizations, both political and apolitical, regarding Judge Kavanaugh’s judicial independence. Judicial independence is as strong a myth in the system of American Jurisprudence as an apolitical court.

In the teaching of American history, there was a euphemism used to discuss slavery: the peculiar institution. The phrase originated in the early 1800s as a “polite” way to discuss the topic of slavery. Southern historians later appropriated the phrase in an attempt to re-brand the image of the New South, i.e., the post-reconstructed South. These historians postulated and taught the paternalistic theory of slavery—that the life of the slave was better because the fatherly master-class took care of the slave’s basic needs. Such phraseology and historical excuses are intellectually dishonest. The question of slavery is one that troubled the founding fathers and the framers of the American Constitution. To see that conflict, one need look at Article 1, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, which reads:

“Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.”

Known as the “Three Fifths Compromise,” it was a stop-gap measure in determining the number of Representatives in Congress from the Southern States. Throughout the 19thcentury, as the nation grew, the debate raged on as to whether a territory or state admitted to the union were permitted to have slaves. Other measures included the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. As the nation grew and slavery became tied into the economy of the South, Southern politicians railed against Northern interference in the “peculiar institution.” The country balanced on a fulcrum of “free” and “slave” states. Each new admission to the Union tipped the balance one way or another. One of the methods the Southern plantocracy used to their advantage was through political patronage and judicial appointments. Southern politicians, such as John Calhoun, were adroit at imposing the will of the South on the nation.

The Question of “Citizenship”

It was not long for the question of slavery to reach the Supreme Court. It did so in the case of Dred Scott v Sanford60 US 393 (1856). As is often the circumstance, the Dred Scott case was two separate cases brought together for Supreme Court review. The slave, Dred Scott, sued under Missouri law and brought a second suit in Federal Court. These are the cases that became the Dred Scott case. The statutes in question were criminal trespass and false imprisonment. The historian Walter Ehrlich wrote extensively on the subject of Dred Scott and discovered heretofore lost court documents of Scott’s state action:

“The origin of any court litigation involves at least two basic issues. The first is grounds—do the law and the facts warrant legal action? The second is motivation—what specific circumstances impel the plaintiff to take his legal action….An investigation of Missouri statutes…reveals quite clearly not only that there were laws which prescribed circumstances under which a slave might become free, but also that ample precedent existed of slaves actually having been freed under those laws…Dred Scott…qualified substantially for his freedom.”[ii]

Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote the majority opinionthat held:

“A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a "citizen" within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States. When the Constitution was adopted, they were not regarded in any of the States as members of the community which constituted the State and were not numbered among its "people or citizens." Consequently, the special rights and immunities guarantied to citizens do not apply to them. And not being "citizens" within the meaning of the Constitution, they are not entitled to sue in that character in a court of the United States, and the Circuit Court has not jurisdiction in such a suit…. The only two clauses in the Constitution which point to this race treat them as persons whom it was morally lawfully to deal in as articles of property and to hold as slaves.”[iii]

Sectionalism as a Deciding Factor

In a 7 to 2 vote the Taney Court declared that the rights and privileges of citizenship did not apply to slaves and freed Africans. In the 20thand 21stcentury the Justices’ votes are often broken down via political lines; the left, the right, the middle. In the 19thcentury, sectionalism dominated the discussion. What section of the country did the Justice represent? There were nine members of the Taney Court:

- Roger Taney (Chief), Maryland: Majority

- John McLean, Ohio: Dissent

- James Moore Wayne, Georgia: Majority

- John Catron, Tennessee: Majority

- Peter Vivian Daniel, Virginia: Majority

- Samuel Nelson, New York: Majority

- Robert Cooper Grier, Pennsylvania: Majority

- Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Massachusetts: Dissent

- John Archibald Campbell, Georgia: Majority

The Court’s majority hailed from states that left the Union in 1860. Chief Justice Taney was from Maryland, wooed by President Lincoln as a border state, and could have been a member of the Confederacy. Of the two Northerners who voted in the majority, President Buchanan pressured Justice Grier to join the majority to avoid the appearance that the ruling ran along “sectional lines.”[iv]The Executive branch used its friendship to influence the political topic of the day. These men on the Supreme Court may have attempted to “rise above” partisan rhetoric. If you examine them within the context of their times, a question arises: when declaring that Dred Scott and the many other slaves were not protected by the laws of man, were they thinking of their own section’s best interests?

Dred Scottwas not the last time the Supreme Court had the opportunity to weigh in on the constitutionality of racial subjugation. The next time the Court sat on this question, the entire national dynamic had changed, though the culture remained.

What do you think of the political nature of the US Supreme Court? Let us know below.

[i]“Brett Kavanaugh’s Opening Statement: Full Transcript.” New York Times¸ September 26, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/26/us/politics/read-brett-kavanaughs-complete-opening-statement.html

[ii]Ehrlich, Walter. “The Origins of the Dred Scott Case,” The Journal of Negro History59 (April 1974):133

[iii]Scott v Sanford,60 US 393 at 393

[iv]John Mack; et al. Out of Many: A History of the American People(Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall, 2005) 388