The Scopes Trial was very possibly the most important of the twentieth century in the US – and has many considerations for today. Here, Edward J. Vinski returns and shares his reflections on Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter in present-day America in the context of the Scopes Trial. You can find out more on the Scopes Trial in Edward’s previous articles over three parts here, here and here.

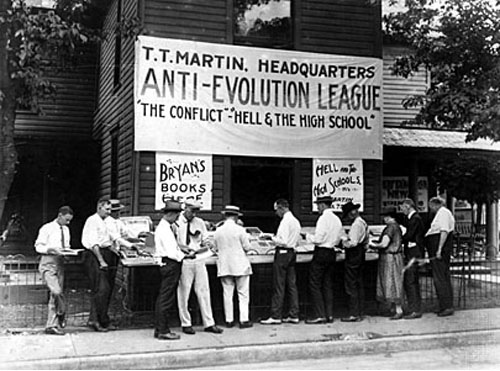

The Anti-Evolution League at the Scopes Trial. Source: Mike Licht, available here.

I write this on July 10, 2016, ninety-one years to the day since the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial began. This court case has fascinated me for well over a decade. I read every book and article I can find about it. I have seen several documentaries. I have watched the dramatization "Inherit the Wind" so often I can almost recite it verbatim. I have thought about it and written about it. I follow new attempts at removing the theory of evolution from the public school classrooms with great interest. Nevertheless, it is only today that I came to a momentous conclusion: We, all of us in the United States of America, may have been wrong about William Jennings Bryan.

Not from a scientific perspective, mind you, because Bryan was no scientist and he often showed his ignorance. He valued scientific achievement for its benefits to humankind, but he had very little understanding of scientific principles. In some instances, his ignorance was nothing short of laughable as in this section from his famous "Prince of Peace" address:

I was eating a piece of watermelon some months ago and was struck with its beauty. I took some of the seeds and dried them and weighed them, and found that it would require some five thousand seeds to weigh a pound; and then I applied mathematics to that forty-pound melon. One of these seeds, put into the ground, when warmed by the sun and moistened by the rain, takes off its coat and goes to work; it gathers from somewhere two hundred thousand times its own weight, and forcing this raw material through a tiny stem, constructs a watermelon...[u]ntil you can explain a watermelon, do not be too sure that you can set limits to the power of the Almighty and say just what He would do or how He would do it. I cannot explain the watermelon, but I eat it and enjoy it (Bryan, 1909).

The argument appears to be, in essence, that science is faulty and God exists because William Jennings Bryan did not know where watermelons come from.

Bryan’s ignorance

Nowhere was his ignorance more evident than in the Scopes Trial itself. In an astonishing development, defense attorney, Clarence Darrow, called Bryan to the witness stand to answer questions about the Bible. Darrow, however, chose his questions carefully from biblical events that pressed up against the boundaries of science. Thus, Bryan stumbled badly when asked questions about such things as the age of the earth, the length of the days in the Genesis account of creation and how these stories contradicted accepted scientific facts. At best, he did nothing to help his cause. At worst, he played directly into the defense's hands.

Bryan was clearly wrong about evolutionary theory. How, then, have we misunderstood him?

Present events

You see, I am also writing this in the wake of a tense week for America. The shooting deaths of black men by police officers in Louisiana and Minnesota were followed a few days later by the shooting deaths of five police officers in Texas. Social media is currently undulating between prayers for the victims, sadness, outrage and anger. In addition, the all too familiar battle lines are once again drawn between Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter.

The names of these movements, however, give a hint of something that Bryan foresaw over nine decades ago: Dehumanization. When we see only the dark skin and the blue uniform, we cannot help but lose sight of what inhabits both - an individual human being. One of Bryan’s greatest arguments for the banning of evolution had nothing to do with science per se. Rather, it was that while science clearly had produced the mechanical marvels of the twentieth century, it had produced no code of morality to keep these marvels in check. Bryan feared that the "survival of the fittest" interpretation of Darwin would lead to eugenics, sterilization, euthanasia and wars of aggression.

For evidence of this, we need look no farther than the textbook under scrutiny at the Scopes Trial, George William Hunter's "A Civic Biology". In a lengthy passage, Hunter describes precisely what Bryan feared most:

Hundreds of families [...] exist to-day, spreading disease, immorality, and crime to all parts of this country. The cost to society of such families is very severe. Just as certain animals or plants become parasitic on other plants or animals, these families have become parasitic on society. They not only do harm to others by corrupting, stealing, or spreading disease, but they are actually protected and cared for by the state out of public money. Largely for them the poorhouse and the asylum exist. They take from society, but they give nothing in return. They are true parasites.

If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race. Remedies of this sort have been tried successfully in Europe and are now meeting with success in this country (Hunter, 1914).

It is noteworthy that Hunter's book was published in 1914, the very year in which a Great War broke out that would eventually see some smaller, weaker nations swallowed up by larger, stronger ones.

War without a moral code?

Bryan worried that the proliferation of evolutionary theory without a proper moral balance would lead humanity to make judgments about those who are fit for life and procreation and those who are not. Those in positions of power could use evolutionary theory as a justification to eliminate those deemed parasitic, troublemakers, or just unpleasant. Had not such philosophies already affected the way we conduct our wars? Science, Bryan wrote:

Has made war more terrible than it ever was before. Man used to be content to slaughter his fellowmen on a single plan-the earth's surface. Science has taught him to go down into the water and shoot up from below and to go up into the clouds and shoot down from above (Scopes Trial Transcript).

No less an authority than the secular evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould seemed to think that Bryan was on to something, writing, "when [Bryan] said that Darwinism had been widely portrayed as a defense of war, domination, and domestic exploitation, he was right" (p. 163). Within a few years of the Trial, Adolf Hitler would show, just how right Bryan was.

Understanding others

We see this same Dehumanization in our day when we look at the tragedies of Louisiana, Minnesota and Dallas. Depending on which side we find ourselves supporting, we see either black skin or a blue uniform, but not the person inhabiting them. Even the reasonable-sounding All Lives Matter perspective, while certainly true in the broadest sense, dehumanizes as it removes all traces of personal identity from the equation and ignores the reality faced by individuals of color and of law enforcement on any given day. For all of our advancements as a society, we have never been able to understand the world clearly from the perspective of another. There are those who cannot see how the actions of a white police officer against a black person could possibly be viewed as racist. There are those, on the other hand, who cannot see how such actions could be anything but. I may be able to sympathize with someone else, celebrate with them in triumph and commiserate with them in sorrow, but I can never truly see how they operate in the world and how the world reacts to them. If I cannot do this among my most intimate of friends, how then, can I ever hope to do so with those I know only through the broadest of generalities, which, by their very definition, dehumanize even further? The "you" and "me" of intimacy become the "them" and "us" of separation. Rodney King, the subject of another period of racial tension a generation ago once asked, "can we all get along?" Until we are able to view the world from the perspective of others, to understand them as individual human beings bound up in a history that is both of their own making and also beyond their control, the answer to that question is likely to remain a sad and resounding "no".

William Jennings Bryan did not understand evolutionary theory. His grasp on the scientific method was sketchy at best. He understood people, however. This skill enabled him to become a three-time candidate for President of the United States and one of the most popular public speakers of the twentieth century. His performance at the Trial led to his being labeled a villain, a bully, a buffoon. Maybe his insight went further than we thought, however. Maybe he knew what we would do to each other given only the slightest provocation and with only the slightest scientific justification. Maybe, just maybe, he was more right than we knew.

What do you think of the article? Tell us below…

References

- Bryan, W.J. (1909). The Prince of Peace. New York: Fleming H. Revel Company.

- Gould, S.J. (1999). Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Hunter, G. W. (1914). A Civic Biology Presented in Problems. New York: American Book Company.

- Scopes Trial Transcript, 1925