The Origins of a Contested Legacy in Russia and Ukraine

In Western Europe, we typically associate Vikings with the storm-tossed waters of the North Sea and the North Atlantic, the deep Scandinavian fjords and the attacks on the monasteries and settlements of northwestern Europe. This popular image rarely includes the river systems of Russia and Ukraine, the wide sweep of the Eurasian steppe, the far shores of the Caspian Sea, the incense and rituals of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the high walls and towers of the city of Constantinople. Yet for many Viking raiders, traders and settlers, it was the road to the East that beckoned.

These Viking adventurers founded the Norse–Slavic dynasties of the ‘Rus,’ which are entangled in the bitterly contested origin myths of both Russia and Ukraine. The Rus ruler, Vladimir (Ukrainian: Volodymyr) the Great, converted to Christianity – in its Eastern Orthodox form – in 988, on Crimea, and so they are at the heart of the concept of ‘Holy Russia’.

Martyn Whittock explains.

Martyn’s new book, Vikings in the East, is here: Amazon US | Amazon UK

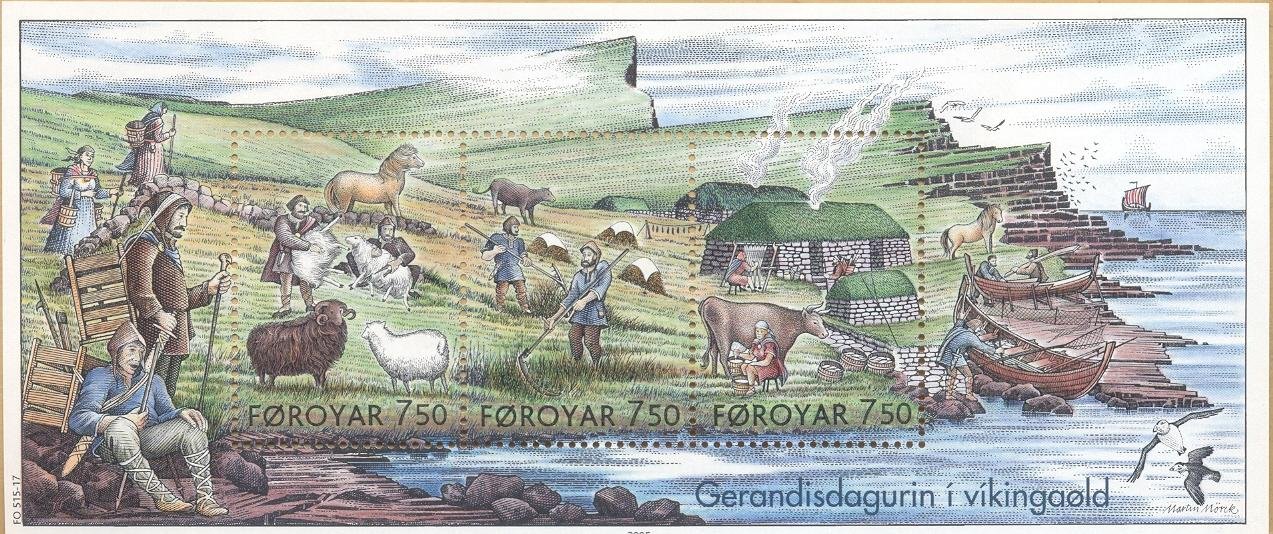

A depiction from the Radziwiłł Chronicle.

Go East!

The East played a major part in the start of the so-called ‘Viking Age,’ in the middle of the eighth century. Alongside various suggested causal factors such as population growth in Scandinavia, cultural conflict with the expanding Christian Frankish Empire, the beginnings of kingdom building in the northern homelands, and agricultural disruption due to volcanic activity, changes taking place in the distant Islamic Caliphate (as the centre of political power there shifted from Damascus to Baghdad) disrupted the flow of silver to Scandinavia. For years, this silver had reached northern Europe, traded for slaves, furs and amber. Facing this change, raiding in the West offered Norse elites an alternative way to get their hands on precious metals and slaves. At the same time, the forest products of the eastern Baltic and the supply of slaves from there drew Swedish adventurers eastward on the austrvegr (the Eastern Way), as it was known in Old Norse. This involved interactions with indigenous Balts, Finns and Slavs that were, at time, mutually beneficial and, at other times, ruthlessly exploitative. No one scenario sums up the complex interactions over several centuries.

The key thing is that the Viking phenomenon increasingly had an Eastern Front. Utilising the river systems, these Vikings soon became active on the Black Sea, the Caspian Sea and in the Byzantine Empire. As a result, vast streams of silver once again flowed north as evidenced by hordes of Arab dirham coins unearthed on Gotland and in Sweden. By the 790s, merchants from the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate (now centred on Baghdad) were expanding their trading journeys up the River Volga and bringing with them good-quality silver again, much of which ended up in Scandinavia. The revival of the flow of silver had a huge impact on Norse trading activities, including slave trading.

From the year 800, huge numbers of silver coins struck in Islamic mints (especially in Central Asia) began to enter Russia and the Baltic region. While this flow of silver appears to have once more slowed dramatically in the 830s (due to renewed turbulence in the caliphate), it picked up again between about 850 and 900 (with a temporary slowing down once more in the 880s). It slowed again in the 970s, before picking up again in the 990s and finally ended in about 1030. When the silver was flowing north, much was funnelled via Gotland.

A striking example of the wide-ranging character of the Baltic trading hub can be found in the thirteenth-century Icelandic Saga of the People of Laxárdalur (Laxdæla saga). In this, an Irish princess, captured as a teenager, is sold to an Icelandic chieftain by a Rus merchant operating on the Swedish island of Brännö. It is an example of slave trading which united the west and east of the Viking world.

Written evidence regarding the Vikings of the East

Evidence for this eastern Norse movement survives on a number of runestones in Sweden. A very important one is located beside the driveway of Gripsholm Castle. When translated, it bears witness to an adventure that went terribly wrong, a very long way from home. The runes in question were carved within the body of a snake that follows the edge of the stone and then curls into the centre. This runic inscription reads:

Tóla had this stone raised in memory of her son Haraldr, Ingvar’s brother. They

travelled valiantly far for gold, and in the east gave (food) to the eagle. (They) died

in the south in Serkland.

The ‘Serkland’ that is referred to on this and on four other runestones was the name used by Scandinavians for the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate and other Muslim areas of the East. The term was either derived from the word ‘Saracen’ (so meaning ‘Saracen-land’) or from ‘serkr’ (gown), referring to the distinctive robes worn by the Muslims living in the East. Either way, it was a long way from home, back in Scandinavia.

This runestone is known today as Sö179, and is one of about twenty-six so-called ‘Ingvar runestones.’ Most of these are found in the Lake Mälaren region of southern Sweden; specifically in the provinces of Södermanland, Uppland and Östergötland. They are named from a Swedish Viking named Ingvar the Far-Travelled, who led an expedition to the Caspian Sea.

This single expedition is mentioned on more runestones that any another event in Swedish Viking history. This points to its importance to contemporary society in the eleventh century. Other evidence indicates that he and most of his companions died in 1041. Some of them died in a fierce battle fought at Sasireti in Georgia, to the west of the Caspian Sea. This battle involved Byzantines (from the Eastern Roman Empire, with its capital in Constantinople), Georgians and Scandinavian mercenaries. The battle was fought in a Georgian civil war. Those that did not die in the battle itself later succumbed to disease far from Scandinavia. These included Ingvar himself.

A twelfth-century Icelandic saga called Saga of Ingvar the Far-Travelled (Yngvars saga víðförla) states that some survivors made it back from the Caspian to Russia. Others travelled on to Miklagarðr, the Scandinavian name for Constantinople. Viking sieges of that great city eventually gave way to more mutually advantageous trading arrangements, even if these were tightly controlled by the Byzantine authorities. In time, many Norse warriors also served in the imperial Varangian Guard.

With regard to the Islamic caliphate, in the late 840s, the Director of Posts and Intelligence in the Baghdad caliphate’s province of Jibal (in north-western Iran), Abu’l-Qasim Ubaydallah ibn Abdallah ibn Khordadbeh, recorded that a group of newly arrived foreign traders, who he called the ‘ar-Rus,’ had brought merchandise to Baghdad on camels. Rus traders had also been noted further east, in Persia. Sailing through the Persian Gulf, they had also reached lands described as ‘Sind, India, and al-Sin’. There are debates over whether the last place named represented Tang China or the khaganate of the Uyghurs. Either way, the route to the East took Norse traders far from home. Islamic travellers also wrote dramatic accounts of meeting Norse traders and slavers of the Rus on the River Volga, in the first half of the tenth century.

The East in the mental world of Norse mythology

Intriguingly, the East also loomed large in Viking-Age mythology, as it did in Viking-Age economics and politics. In this area of life, East met West in the world of the gods and goddesses of Norse mythology. The key source for this is the Saga of the Yngling Family – usually simply referred to as Ynglinga Saga. This is the first part of the Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson’s history of the ancient Norwegian kings, which is titled Circle of the World (Heimskringla). The earliest part of this saga claims to deal with the ‘arrival’ of the Norse deities in Scandinavia. In this section, it is explained that they originated in a part of Asia to the east of what is called the Tana-kvísl river. From Snorri’s explanation, this river is what we now call the River Don. The River Don flows from south of Moscow to eventually reach the Sea of Azov, which is linked to the Black Sea. Now in southern Russia and eastern Ukraine, this region borders the Caucasus to the south. Snorri also knew the river in question as the Tanais (Tanais being a settlement in the delta of the River Don). The region east of the Tanais was, according to Snorri, the location of the original city of the gods.

The ‘geography’ of this account in Ynglinga Saga was clearly inspired by knowledge of strange lands in the East that had actually been explored by real-world Viking-Age traders. However, it had later been reinvented in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Norway and Iceland as a fabulous ‘never-never land’ that was situated far-far away. This is revealed by the fact that, in Snorri’s account, Odin’s eventual journey to Scandinavia is described as being via the Don and Volga rivers and through Garðaríki, the Old Norse name for the lands of the Rus (the ‘Kingdom of the Towns’). Odin’s route in the mythological story was, in reverse, the historic Viking routeway to the Byzantine Empire and Serkland, the Norse name for the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate. In other words, the Viking-Age divinities were described as traversing the very same river routes as the real-life traders of the ninth and tenth centuries.

Many Norse traders and adventurers used this eastward route and, in time, plugged into the western end of the Silk Roads that stretched across Eurasia as far as Japan. Trade routes which started in Scandinavian trading centres such as Birka (Sweden), Hedeby (Denmark, now Germany), and Gotland (Sweden’s largest island), extended far into western Eurasia along the river systems of the modern nations of western Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. Many Norse travelled the rivers to the Black Sea and the Byzantine Empire; others journeyed to the Caspian Sea and beyond.

The Norse and origin stories in Russia and Ukraine

In the twelfth century a source of information known as the Tale of Bygone Years (Pověstĭ Vremęnĭnyhŭ Lětŭ) was compiled in what is now Ukraine. It is now generally known as the Russian Primary Chronicle or the Tale of Bygone Years. According to this account, Viking adventurers (called the Varangian Rus) used force to subjugate the Slavic and Finnish tribes living south-east of the Baltic. But, the chronicler tells us, they were then driven out. However, once free of the Rus, warfare broke out between the indigenous tribes and they decided that, perhaps, the rule of the Rus was not so bad after all. Consequently, they invited them back to bring order. This is clearly later spin designed to enhance the prestige and legitimacy of those ‘invited back.’ It has a rather modern – colonialist – feel to it.

The curious thing is that the original ‘colonial perspective’ was penned by one of those colonised, not by one of the outside colonisers. This, though, is readily explained. Whoever wrote this interpretation of the foundation of the Rus state was one who was heavily invested in it. Therefore, although the spin was sharply patronising in tone regarding the capabilities of the indigenous Slavic and Finnish peoples, its purpose was to trace the arc of history in a providential way. As a result, it was narrated in a way that revealed the ‘good order’ brought by the newcomers, who would eventually be founders of the state and – crucially – converts to the Orthodox Christian faith.

The three brothers referred to in the Russian Primary Chronicle (and the towns they were credited as founding) were: Rurik (or Riurik) in Novgorod, Sineus in Beloozero and Truvor in Izborsk. The last two may be Slavic versions of original Old Norse names: Signjotr and Thorvar. Rurik, who was to give his name to the Rus dynasty itself (the Rurikid), represents a name that was originally something like Old Norse Hrøríkr or Rorik.

According to the Russian Primary Chronicle, the Viking brothers were of the Varangian tribe of the Rus. This is a designation designed to clearly signal that they were the people who eventually gave rise to the state of the Kyivan Rus, using the ethnic names known to both Slavs and Byzantines for the Norse in, what is now, Russia and Ukraine. Their return as rulers, the chronicler suggests, occurred sometime around 860/862. When Sineus and Truvor died, Rurik amalgamated their lands under his rule and so was formed the nucleus of what would become the princedom of the Rus. The source now called the Novgorod First Chronicle (Novgoródskaya pérvaya létopisʹ), describing events from 1016 to 1471 and drawing, in part, on eleventh-century sources, also records this story of an invitation to foreign rulers to come and bring order and law.

The Russian Primary Chronicle also claims that, while Rurik was establishing himself at Novgorod, two other Rus leaders – Askold and Dir – travelled southward down the river Dnieper and established their rule in the settlement later known in Russian as Kiev (Ukrainian: Kyiv). It is likely that they took control of a trading post of the Khazars, who were already exploiting a favourable position on the Dnieper river route to the Black Sea.

If the Russian Primary Chronicle’s dating is correct, this set up two rival Rus mini-states: Novgorod in the north and Kiev/Kyiv in the south. Rurik ruled until c. 879. His successor, named Oleg or Oleh (a Slavic form of the Old Norse personal-name Helgi) then struck south and seized Kiev/Kyiv in c. 882 and relocated his capital there. The Russian Primary Chronicle says that, in so doing, he killed Askold and Dir, the Viking chieftains who had established their rule there a little earlier.

In this way, the new state of (what is often called) the Kyivan Rus was traditionally established. It would last until the 1240s, when it fell to the Mongols. Over time it became increasingly Slavic in culture, since the Norse were always a minority. However, the last Rurikid (the dynasty claiming descent from the Viking Rurik) to rule Russia did not die until the late sixteenth century. After a time of extreme turbulence, the next Russian dynasty, in the early seventeenth century (the Romanovs), manufactured connections with the older royal line stretching back to the Norse founders of the Rus state. Rulers after them continued to reference these ancient roots, as rulers of Muscovy sought to extend their authority south into, what is now, Ukraine. This, they claimed, was a ‘gathering in of the Rus lands.’

A contested legacy

After the destruction of the Kyivan Rus state, by the Mongols in the 1240s, Russian rulers (based in Moscow) have frequently referenced these Norse origins when trying to enhance their power and secure control over the Ukrainian lands.

Since the eighteenth century the credit that foreign Viking incomers were accorded in the formation of Kyivan Rus has fluctuated over time, in line with changing Russian politics. This is sometimes termed the ‘Normanist debate.’ In the mid eighteenth-century, foreign involvement in the formation of Russia became intellectually unacceptable. However, it became more fashionable again in the nineteenth century as tsars married into German royal families and relished tales that Russians needed the strong hand of autocrats to bring order.

Under Stalin, in the 1930s, promoting the idea of foreign founders of Russia would – and did – bring a death sentence. It hardly helped that Hitler claimed, with predictable Nazi racism: “Unless other peoples, beginning with the Vikings, had imported some rudiments of organisation into Russian humanity, the Russians would still be living like rabbits.”

Under Vladimir Putin the wheel has turned again. The Rus origin story is central to his insistence that Russia and Ukraine are one people, with Moscow now the dominant force. In 2015, when Putin sought to justify his annexation of Crimea from Ukraine, in 2014, he asserted that Crimea has “sacred meaning for Russia, like the Temple Mount for Jews and Muslims,” and, furthermore, that Crimea is “the spiritual source of the formation of the multifaceted but monolithic Russian nation.” He added: “It was on this spiritual soil that our ancestors first and forever recognized their nationhood.” He was referring to the Christian baptism of the Rus ruler, Vladimir the Great, in 988.

In 2016 a massive statue of Vladimir the Great was erected in Borovitskaya Square, in central Moscow. It was unveiled by his namesake: Vladimir Putin. The erection of the statue was immensely controversial because St Vladimir – called St Volodymyr in Ukrainian – is claimed by both Russia and Ukraine as a founding father and many Ukrainians considered it a provocative gesture. It was highly significant that the statue was unveiled on National Unity Day in Russia – a national holiday revived by Putin in 2005. At the time, many Ukrainians felt that the action was a deliberate attempt to challenge the idea of Ukrainian sovereignty and cultural independence.

In 2021, prior to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine by Russia, Putin once more referenced the ancient Rus as founders of a united state (a view which denied Ukrainian sovereignty). Then in 2024 – in conversation with the US conservative commentator Tucker Carlson – Putin explicitly referred to the Norse roots of the Rus as a way of claiming that Russia is now the legitimate heir of ancient European traditional culture, not the Liberal West.

In conclusion, the Vikings of the East have been on a journey over time that is comparable to the immensity of their geographical journey in the ancient past. And, in the conflicted world of the twenty-first century, it is clear that the ‘journey’ of the Vikings of the East is far from over!